Ten years after the end of the American Civil War, some Confederate veterans were back in action, fighting as mercenaries in Africa. One of them rose to a high rank in the Egyptian army, and played a key role in an attempt – that ended in disastrous defeat – to forge an empire in eastern Africa. Following are thirty things about that and other fascinating Civil War facts.

30. Confederates in Africa: Not a Politically Incorrect Joke

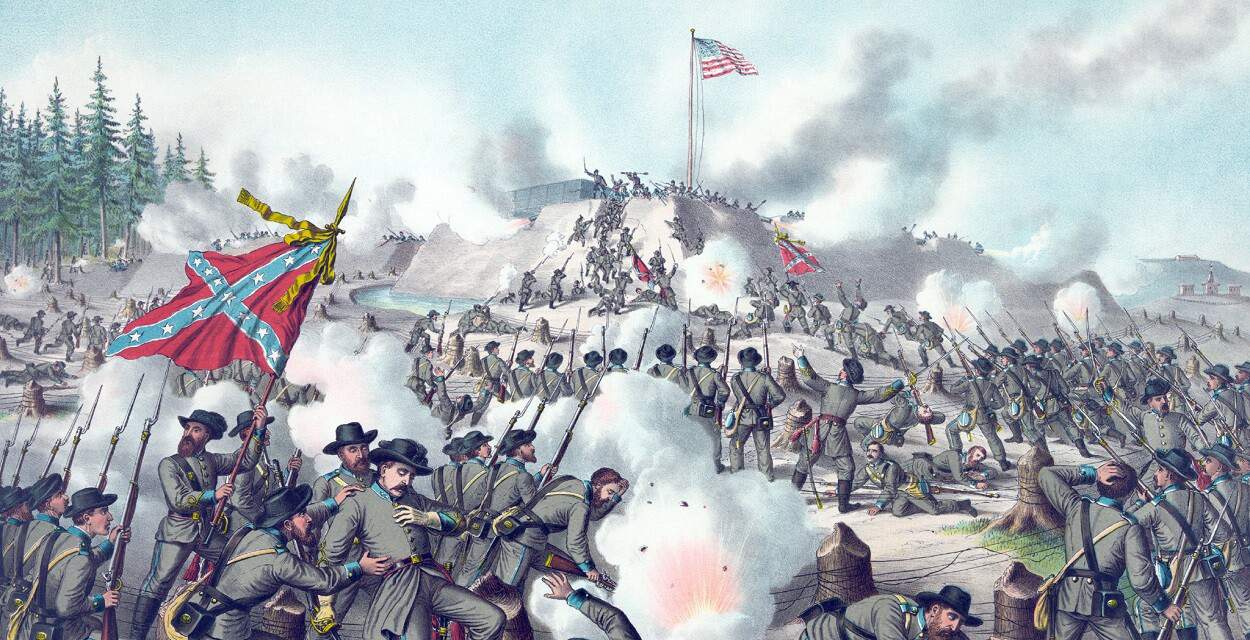

Archive Photos

Confederates in Africa sounds like the start of a joke, along the lines of the one defining chutzpah as a Ku Klux Klan chapter in Nigeria. However, unlike the KKK bit, Confederates actually did head to and fought in Africa. To be sure, by the time that happened the Confederate States of America had been defeated and consigned to the trash heap of history, and the Confederates in question were veterans of the defunct state. Still, theirs is a fascinating tale.

It began in 1868, when Union Army veteran Thaddeus Mott met Egypt’s ruler, the Khedive Ismail, and regaled him with tales about American military advances during the US Civil War. Ismail was convinced to hire veterans of that conflict to help modernize the Egyptian army. The first of them, Confederate veterans William Wing Loring and Henry Hopkins Sibley, arrived in 1870. Loring became the Egyptian army’s Inspector-General, and in 1875 was appointed chief of staff of an army sent to fight Ethiopia.