As long as there have been governments, there have been protests against them. From the earliest days of human history, we have heard tales of the masses rising against the powers that be with the goal of changing their ways: there are stories of strikes by workers building the pyramids of Egypt, of popular leaders such as Spartacus and of slave revolts all over the Ancient World. The nature of feudal society did not lend itself to successful protest – those who questioned authority were often the swiftest victims of it, a trend that has continued to this day – but there has always been movement from below through which people have endeavored to collectively act in defense of their rights.

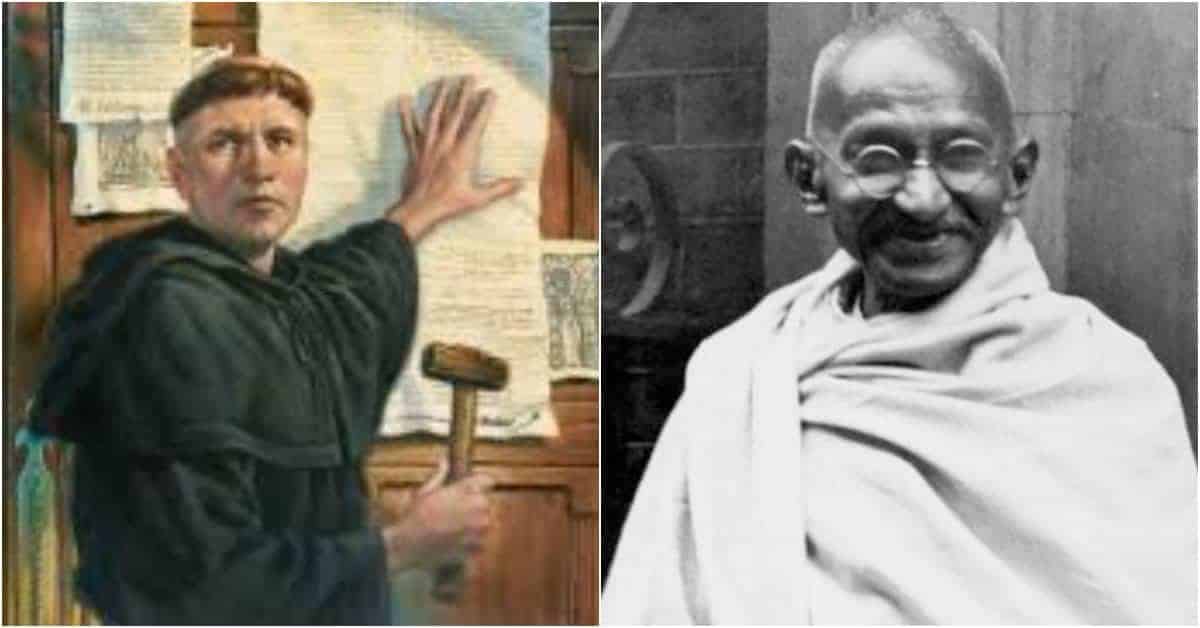

There have been non-violent actions, designed to show dissent and dignity, there have been symbolic actions, crafted to make a point that stands for a larger whole – and of course, there have been full on rebellions, dedicated to using all means necessary to wrest power by force. Our list of the most important protests in human history takes in them all – let us talk you through some of the most influential and most lasting popular demonstrations that have shaped the world that we live in today.

There have been non-violent actions, designed to show dissent and dignity, there have been symbolic actions, crafted to make a point that stands for a larger whole – and of course, there have been full on rebellions, dedicated to using all means necessary to wrest power by force. Our list of the most important protests in human history takes in them all – let us talk you through some of the most influential and most lasting popular demonstrations that have shaped the world that we live in today.

1. The Peasants’ Revolt

The earliest example of a popular protest is hard to pin down. Some will cite the slave revolts mentioned in The Bible, or uprisings against monarchical dynasties in China. We can’t verify them and thus we leave them to speculation: instead, we begin our journey through protest in Mediaeval England.

Life in 14th century England was, to quote Hobbes, nasty, brutish and short. It was particularly unpleasant if you happened to be poor, which the vast, vast majority of the population was. Most people worked the land as serfs, beholden to one landowner and required to work the land for that matter, with only a small portion on the side with which they could feed themselves.

There were masters and there were villains, and if you were a villain then your life revolved around doing basically whatever the lord of the manor fancied you to do. Villeins were indentured slaves, taxed to the hilt and unable to work or move freely. All you wanted was a plot of land to call your own and the right to farm freely.

What you didn’t want was the Black Death, either, which arrived in 1348 and killed somewhere around half of all peasants. While this was bad for those killed (obviously), it did hand the surviving villeins a decent hand economically speaking. With 50% fewer villeins around and the same amount of land, they could maneuver against the masters for a better deal.

In 1381, they did just that. When the King’s official, John Brampton, attempted to take poll taxes from peasants in Essex to pay for the ongoing war in France, he was met with resistance by locals. The rebellion spread and suddenly villains had taken arms and were burning all records of their bondage, emptying the jails and attacking anyone with a whiff of royalty about them.

The mob, lead by serf Wat Tyler, marched towards London and managed to take the Tower of London, destroying the Savoy Palace and killing the Lord Chancellor and the Lord High Treasurer. They were met at Mile End by the King himself, aged just 14. He agreed to abolish serfdom.

The next day, however, he met with Wat Tyler, wherein a battle ensued and Tyler was killed by one of Richard’s entourage. With the leader slain, the King’s forces began to roll back the concessions they had granted and, in the end, the Peasant’s Revolt was put down with thousands killed across England. The influence of the revolt would be lasting, however, with future monarchs reticent to ever raise taxes on the peasantry and always aware that consent of some form was required to govern the people.