Late fourteenth century England was not a pleasant place to be. The Black Death had swept the nation a few decades before, changing the social dynamic of the country. England and France had been fighting in the Hundred Years’ War for the past fifty years, and the state was politically unstable. The boy king Richard II had inherited the throne from his grandfather, Edward III, and his despised royal councils had imposed a series of taxes that were particularly harsh on the lower classes to raise money for the war effort.

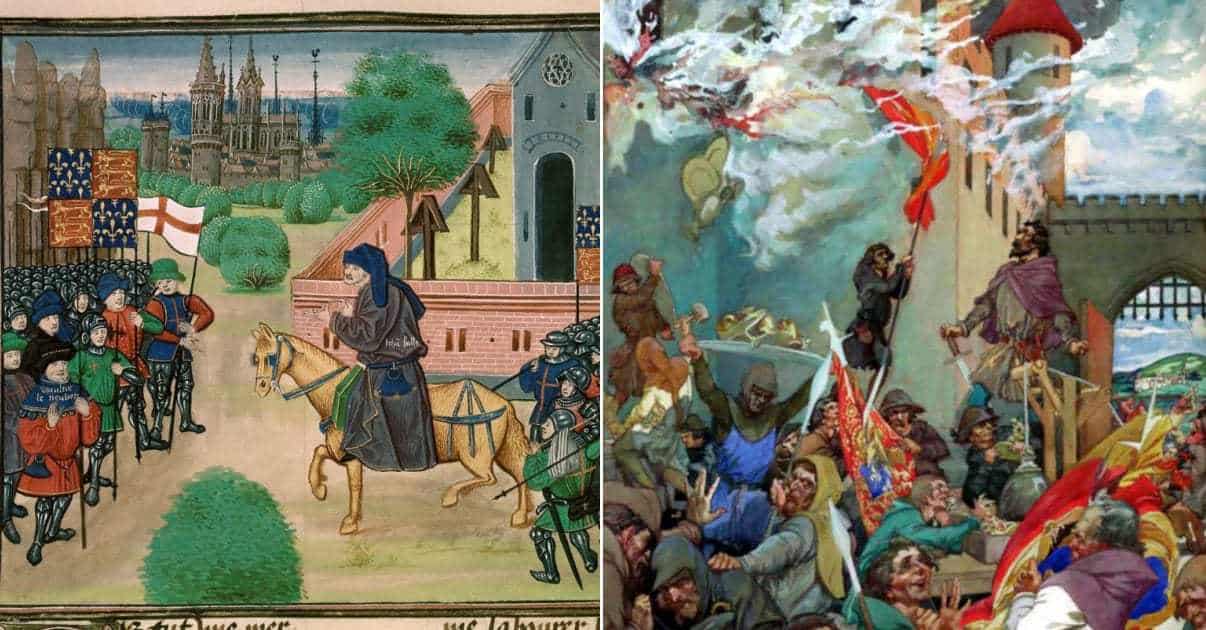

In June 1381, thousands of workers from Kent in southeast England marched on London to confront the government officials responsible for passing strict taxation and labor laws against them. Many Londoners had opposed the government for years, and the combination of Kentish and London agitators descended London into chaos: they attacked and burned buildings and homes, and they murdered government officials on sight, with the king and his advisors huddled in the Tower of London in fear for their lives. Known as the Peasants’ Revolt, it became England’s first great popular uprising: the revolution spread all over the country, and the government did not re-establish order until the end of the year.

The fourteenth-century economy depended on manorialism, an economic practice in which lower-class workers (serfs) lived on estates owned by wealthy, upper-class landholders; in exchange for living on the land and having a small amount of it to cultivate for themselves, the serfs had to provide labor for the estate. Serfs had varying degrees of mobility, but for the most part, they were permanently tied to the land, and they couldn’t leave without the permission of their lord. By the middle of the century, the Black Death arrived in England, killing about 50% of the population.

With the decrease in population, the lower-class workers realized that they were in demand, and they began to push for better working conditions and higher wages that the landowners did not want to provide. The royal government passed labor and tax laws that favored the landowners and began to limit the movement of the peasantry by fixing wages and fining serfs for breaking their contracts. The upper classes feared that the laborers that moved from place to place would incite other peasants to rebel. The government used conspiracy and treason laws to limit the travelers’ movements and influence, which increased the resentment.

In 1380, another law taxed each person at a flat-rate poll tax, which was more economically difficult on the lower classes than on the upper classes. Collecting these taxes was an issue because most of the people who were forced to pay them didn’t have it to give. The southeast of England was especially outraged, and many people in this area refused to register to pay the tax. Richard II’s royal advisors sent tax investigators around the country to find out who wasn’t paying the taxes, which further offended the people of southeast England.