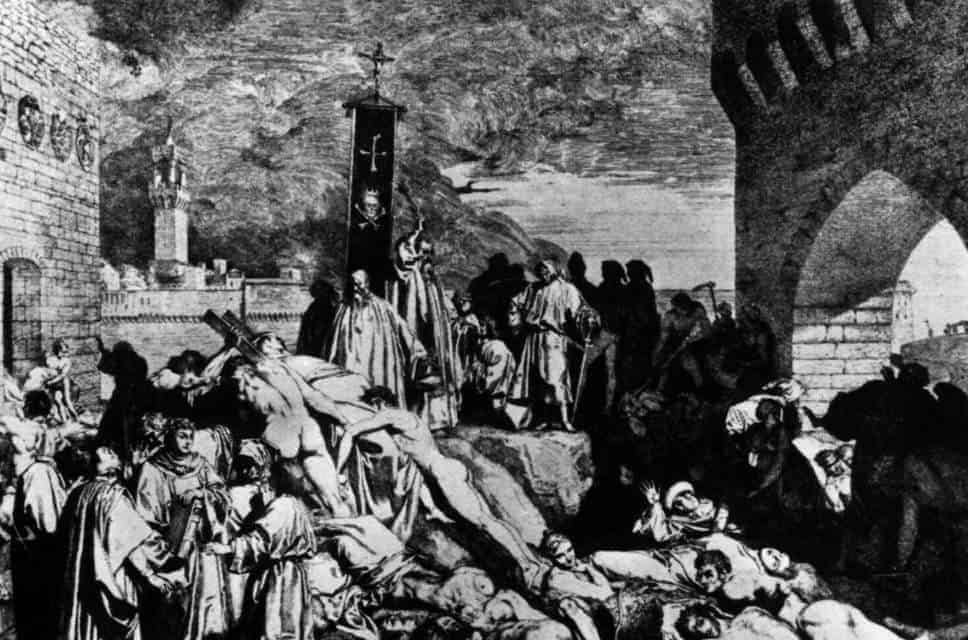

The Bubonic Plague, colloquially known as the Black Death, was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history. An estimated 75 to 200 million people died in Eurasia, with the peak of deaths occurring between 1347 and 1351. The Black Death killed 30 – 60% of Europe’s population, and it took over 200 years for the world’s population to recover to its pre-Black Death level. At the center of this pandemic were the body collectors, tasked with collecting and transporting the countless victims of the plague to their final resting places in mass graves.

1. One Monk Buried 34 of His Brothers Alone

Francesco Petrarca, commonly anglicized as Petrarch, is a renowned Renaissance Italian humanist. His extensive writings helped the development of standard modern Italian. He was a close friend of the famous author and plague chronicler, Giovanni Boccaccio. While far less known, Francesco’s brother, Gherardo Petrarca, was a fantastic person in his own right.

Gherardo served as a brother at the Montreux monastery in what is now Switzerland. The plague typically hit isolated communities like monasteries, abbeys, and nunneries particularly hard due to the close quarters and frequent contact between the residents. Religious communities often helped tend to the sick as well, which increased their exposure to the plague. Many monasteries had their entire populations fall to the Black Death.

Gherardo’s monastery was one of those devastated by the plague. He was one of 35 brothers at the monastery, and the only one to survive. The only other living thing to survive the epidemic at the monastery was his dog. He undertook the heartbreaking and exhausting labor of burying every single one of his 34 brothers alone. It is hard to imagine a sadder and more isolating fate than burying every single one of your companions. His famous brother, Francesco, also died of the plague in 1361.