“War is always the same. It is young men dying in the fullness of their promise. It is trying to kill a man that you do not even know well enough to hate. Therefore, to know war is to know that there is still madness in this world.”

So wrote Lyndon B. Johnson, of the Vietnam War, in his State of the Union Address in 1966, when that conflict was at its height. War is as old as humanity and the association between war and madness is one that has been around as long as conflict itself. The theatre of war is one of the few areas of life where being slightly bonkers is actually a help rather than a hindrance: the ability to place oneself in the path of danger without regard for the consequences, to put fear to the back of one’s mind, to continue when all sense would tell one to give up – these are values that are beneficial in a soldier that would mark out an average person as a madman. Of course, the madmen that we list in this article are the ones, largely, who survived to tell the tale, or at least, were around to have their story told for them. The majority of crazy soldiers end up heroically dead, a status in which the second word somewhat outweighs the first.

There is an arresting line in the final episode of the classic British comedy Blackadder Goes Forth, set in the trenches of World War One and ending with the slaughter of all the characters, in which the captain of the troop – who has previously attempted to get out of going “over the top” by claiming to be mad – reflects on the futility of such an act in the midst of such a conflagration. “Who would have noticed another madman around here?” says Captain Blackadder, before facing his fate.

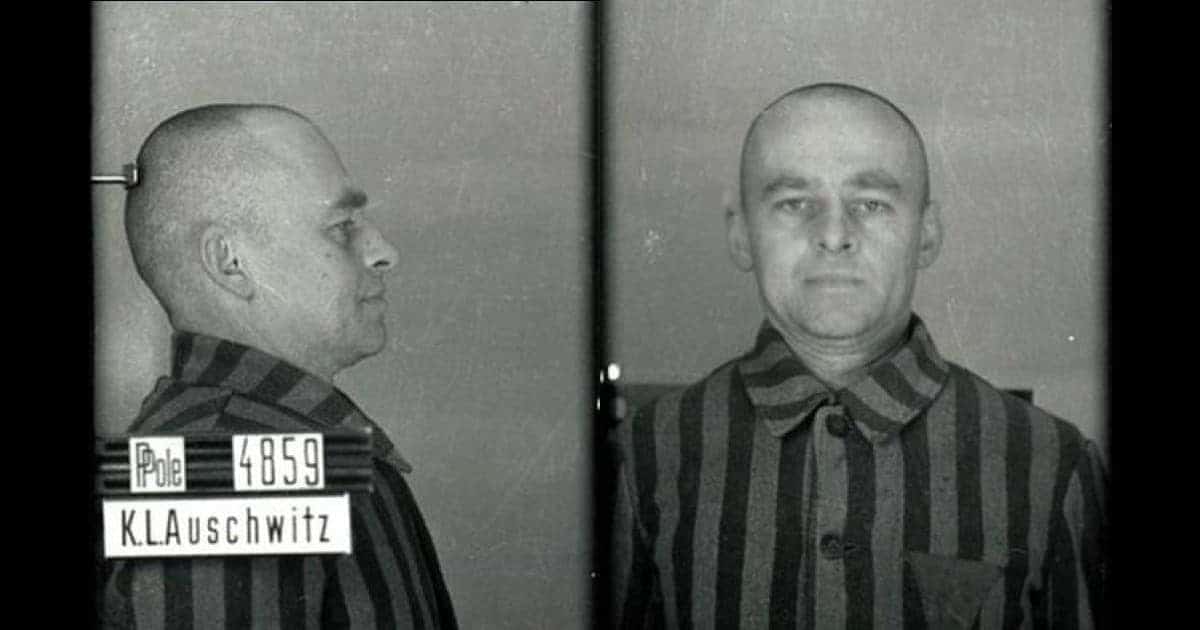

Our list, drawn from combatants in the Second World War, brings together a motley crew of soldiers who were crazy enough to run into fire and calm enough to go behind enemy lines, smart enough to think of hare-brained schemes and mad enough to then carry them out. We travel through all the major theatres of the conflict and a few lesser-known ones as well, taking in resistance fighters from Czechoslovakia and Finland, a British stage magician who made an army disappear, a Polish count who snuck into Auschwitz and a legless fighter pilot and a Japanese soldier who kept on fighting until 1974. These are the fighters who make Rambo look sane: the 12 Craziest Soldiers of World War Two.

1 – Jack Churchill

There are plenty of mad soldiers out there, so to gain a reputation for being slightly nuts among fellow fighters is quite impressive. Jack Churchill – aka “Fighting Jack”, aka “Mad Jack” was about as mad as they come and thus is the ideal person with which to begin this descent into insanity. He was known for the phrase “Any officer who goes into action without his sword is improperly dressed” and certainly lived up to that reputation: he would run into battle clutching a Scottish broadsword, supplemented by a longbow and also carrying a full set of bagpipes. That’s unusual enough, but it gets weirder: Jack Churchill wasn’t even Scottish.

His story was similar to many of the British officer class in the Second World War: he was born to a military family that was stationed abroad in the colonial service – in Jack’s case, Hong Kong – and educated at a private school back in the old country. He went through Sandhurst, the main officer training finishing school in Britain, before being posted to Burma. Churchill did ten years before leaving the army and beginning to indulge his eccentricities. He was at various points an actor, a male model and a newspaper editor, while also winning competitions for his archery and bagpipe playing (which was seen as an outrage, as an Englishman had beaten many Scots at piping).

By the time the Second World War broke out, Jack Churchill was more than ready to emerge as “Mad Jack“. He rejoined and was sent to France along with the Manchester Regiment. His first action as an officer was to kill a German sergeant with a longbow – the first and only confirmed longbow kill of the entire war. “He and his section were in a tower and, as the Germans approached, he said, ‘I will shoot that first German with an arrow,’ and that’s exactly what he did,” later explained his son, Malcolm.

Churchill was involved in the Dunkirk evacuation and, after repatriation, fought in Norway, where he lead a charge while playing “The March of the Cameron Men” on his bagpipes. Later in Italy, he took part in the Salerno landings – Scottish broadsword, longbow and pipes in tow – and in Yugoslavia, where he took command of a 1500 strong force before being captured on the island of Brac, having alerted his fellow commandos to the attack by playing a Highland march on his bagpipes. Subtlety and stealth were not among Jack Churchill’s strong points.

Churchill escaped twice – once walking over 200 kilometers from Berlin to Rostock before being taken prisoner again – and eventually was moved to a camp in the Austrian Tyrol. When the Germans left, fearing the advancing Allies, he walked 150 kilometers to freedom in Italy. Mad Jack finished the war in Burma in 1945, where, it is reported, he was disappointed that the Americans had dropped the nuclear bombs on Japan and ended the war, saying “If it wasn’t for those damn Yanks, we could have kept the war going another 10 years!”

Peacetime did not suit Jack Churchill and he struggled to settle back into civilian life. Stories abounded of his further eccentricities: one held that he would launch his briefcase into his own garden as the train passed his home, to save him carrying it with him, while another told of his exploits surfing on the River Severn. He died in 1996, laying to rest a man who, frankly, appears not to have enjoyed the idea of sitting still one little bit.