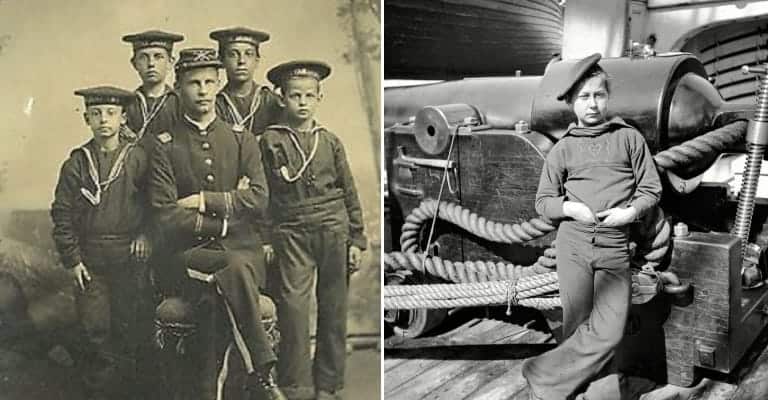

From time immemorial, just about every child has dreamt of adventure and excitement. For many boys, the military is high on the list of the adventurous and exciting – the uniforms, the guns, and the camaraderie. Even the fighting, which tickles their fancies with dreams of glory and returning home as heroes. However, while most boys dreaming of a military career wait until they grow up before following through, some are too impatient to hold off on enlisting until they come of age. Following are forty fascinating things about some of America’s youngest warriors.

40. Kids in Naval Combat

Naval combat during the Age of Sail boiled down to warships firing broadsides at each other from rows of guns lining their fighting decks. Speed of discharging and reloading the cannons and maintaining a rate of fire was vital, so the last thing anybody wanted was for the guns to run out of ammunition mid-fight. Stockpiling cannonballs next to the guns was simple, but stockpiling gunpowder nearby was problematic: it was too dangerous to leave large amounts of powder on the gun deck.

One errant spark in a space full of sparks and flames during combat could spell disaster for the ship. So a system was devised to send a steady stream of small amounts of gunpowder from the ship’s magazine or Powder Room, located beneath the waterline, to the guns. Sailors rushing back and forth between the Powder Room and guns, bearing relatively small amounts of gunpowder each trip, reduced the risks of catastrophic explosions. It did not take long before naval authorities realized that the ideal gunpowder courier was a child.