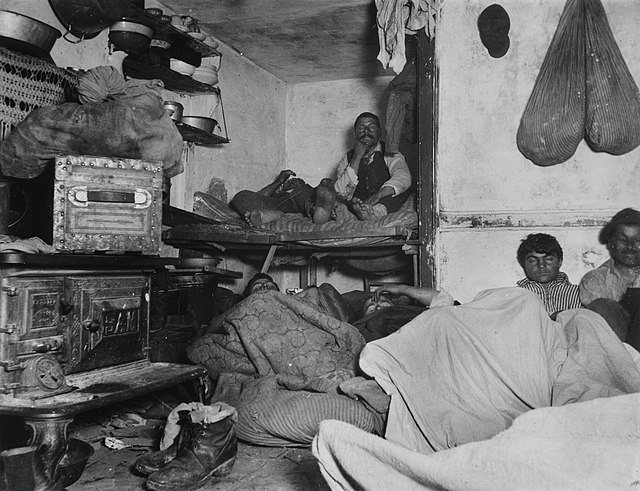

The masses of immigrants coming to America and settling in New York in the 1800s needed cheap housing. New York’s Lower East Side, as a hotbed for these affordable units, attracted thousands of these immigrants and others coming to the city to find work. But these newcomers found not the gold-paved streets of their dreams, but squalor and danger in the city’s low-rent tenements. In 1890, reporter Jacob Riis shocked the nation by publishing his photographic journal, How the Other Half Lives. His collection of photographs, taken in New York’s Lower East Side, wasn’t just a missive on the area’s poverty, it pleaded for conditions to change. Between 1902 and 1914, the New York City Tenement House Department started documenting the tenement conditions. Their photographs live on as a testament to the time when merely renting a space to live in put the tenants’ lives at risk.

Tenements Were Tight Quarters

In New York, tenements crowded into city blocks, taking up the whole block to maximize the rentable space. Squeezed between other tenements, they would be about 25 feet wide and 100 feet long (7.6 meters by 30.5 meters), with only a foot or less between neighbors. With so little space between buildings, windows couldn’t fit on the side of the building.

Only the street-facing units had windows. They were five, six, or seven story walk-ups with terrible ventilation; with little window space, the only fresh air would come from the main entrance and the rooms facing the street or rear yard. Jacob Riis counted twelve adults sharing a room only 13 feet across, and discovered infants were dying at a rate of 1 in 10, a shocking mortality rate, even for the times and in that location. Tenements were a terrifying, but often only, choice for the poor.