Although the Wild West was never as wholly anarchic and wild as Hollywood likes to depict it, it was wild enough. In an era before widespread and effective law enforcement, there was plenty of room for violent men to engage in, and often get away – at least for a while – with criminal acts that would have seen them safely locked up, or even more safely executed, in the more settled parts of the country. Following are forty fascinating things about some of the wildest men of the Wild West.

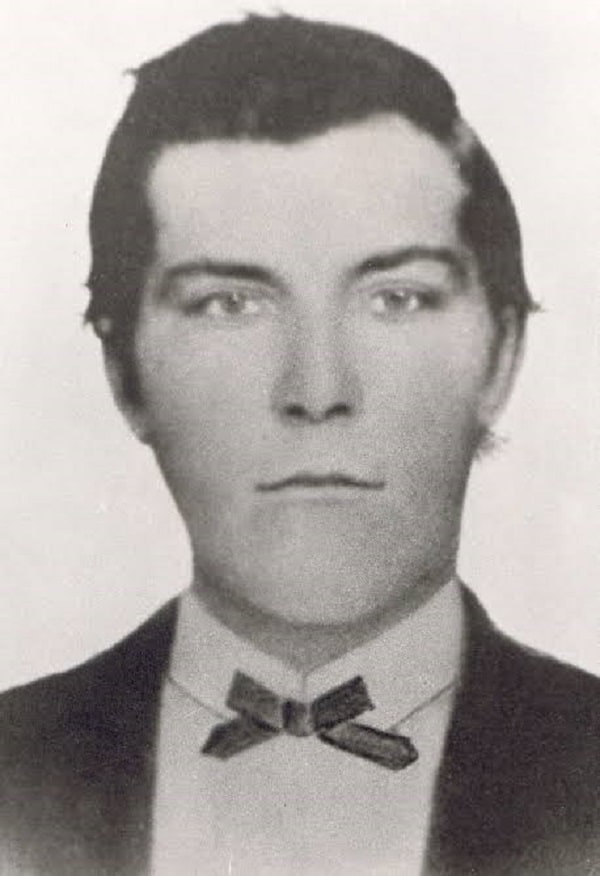

40. The Deadliest Gunslinger?

John Wesley Hardin (1853 – 1895) might have been the Wild West’s deadliest outlaw and gunslinger, with dozens of victims – including a man whom he shot for snoring. According to his own claims, which might or might not have been exaggerated, he killed 42 men. Contemporary newspapers verified 27 killings that were attributed to Hardin.

The son of a Methodist minister and a member of a prominent Texas family that included a judge and a legislator, Hardin was a bad ‘un from early on. His violent career started in 1867 with the stabbing of a schoolmate, and a year later, at age fifteen, he shot and killed an uncle’s former black slave in an argument over a wrestling match.