During America’s Civil War over 150 military prison facilities dotted the country, North and South. Some were used to hold prisoners for a short time until they were paroled. In the early months of the war, opposing commanders often exchanged the prisoners they held, informally. The exchange system broke down early in the war, and later Union commanders opposed returning Confederate prisoners since many would soon serve again. Camps erected to house small populations for short terms became overcrowded with prisoners. The system to feed them, provide proper medical care, and shelter them broke down as well, especially in the south. One Confederate prison, Andersonville, became synonymous with suffering during the American Civil War. Its official name was Camp Sumter, and it didn’t open until 1864. In just over a year, 13,000 Union soldiers died there.

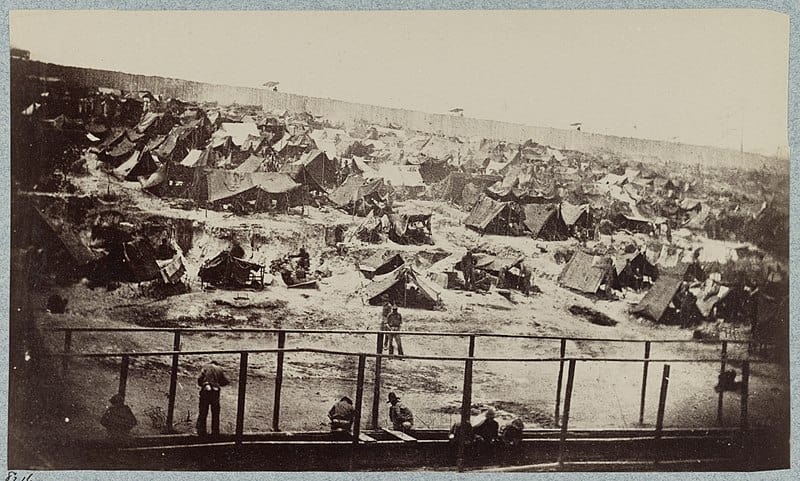

Over the course of 14 months, more than 45,000 Union prisoners were sent to the camp, built to hold less than a quarter of that amount. At its peak, in late summer of 1864, 33,000 men crowded the stockade. They lacked adequate shelter, decent food, fresh food of any kind, and medicines. During the summer of 1864 over 100 men died daily, buried outside the stockade without coffins or even clothes on their bodies. The camp was under the authority of General John Winder, who once boasted of “killing more Yankees than twenty regiments of Lee’s army”. Immediately under him in the chain of command stood Captain Henry Wirz, commandant of the prisoners. Between them, they oversaw a living hell for Union prisoners for 14 months. Civil War POW camps were horrors on both sides, but none were worse than Camp Sumter. Here is some of its story.

1. The Dix-Hill Cartel established an exchange system in the summer of 1862

General John Dix and Confederate general D. H. Hill established an exchange arrangement through which certain individuals were more valuable than others. For example, a Navy Captain or Army Colonel could be exchanged for fifteen sailors or privates. All ranks exchanged equally, private for private, lieutenant for lieutenant, and so on. The cartel established two locations for the exchanges, Vicksburg, Mississippi and Aiken’s Landing, on the James River in Virginia. Both sides agreed to establish agents in those locations to handle the exchanges and ensure the rules were followed. The cartel also established the freedom of opposing commanders to exchange prisoners under a flag of truce, either directly or through paroling prisoners. Parole consisted of the prisoner agreeing to not return to a military role until he was formally exchanged. This freed commanders from the burden of feeding and guarding prisoners.

The first formal exchanges took place in August 1862. In less than a year the system broke down. Both sides took steps to avert the rules and attempted to gain numerical advantages over the other. The makeshift camps on both sides created to hold prisoners for just a short time swelled with captives. The Confederate government refused to parole and exchange Black prisoners, arguing they were escaped slaves and thus private property. Following the 1863 Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg few exchanges took place, and in 1864 Ulysses S. Grant ordered them suspended completely. By then, both sides held large numbers of prisoners and established larger facilities to house them. One such facility, on the Confederate side, was Camp Sumter. Established in Georgia in February 1864, it became better known by the name of the nearby small town of Andersonville.