Even before the internet came to spread myth and falsehood with extraordinary speed legends and myths became a part of American history. Today myths spread unchecked. One of the reasons for their growth is sloppy research, leading to circular reporting, with unconfirmed and inaccurate accounts appearing on multiple sites, citing each other as sources when they cite sources at all.

It is possible to present history with differing interpretations of the same event or events and remain true to events, but recreating the event or creating new out of whole cloth is another thing altogether. After several decades of folklore and unverified tales passed down as folklore, much of what most think they know about their history is wrong.

Some of these myths have long been debunked but never completely go away. George Washington and the cherry tree is an example. Both David Crockett and Daniel Boone are remembered, in part, for their courage against Indians on the frontier, though neither was a particularly enthused Indian fighter. Edison improved the lightbulb, he didn’t invent it. Assembly line manufacturing was in use long before Henry Ford installed it in his River Rouge Plant. Gunfighters and quick draw gun battles were scarce in the American West, with most communities enacting laws making the carrying of guns in town illegal. Here are 20 more myths of American history.

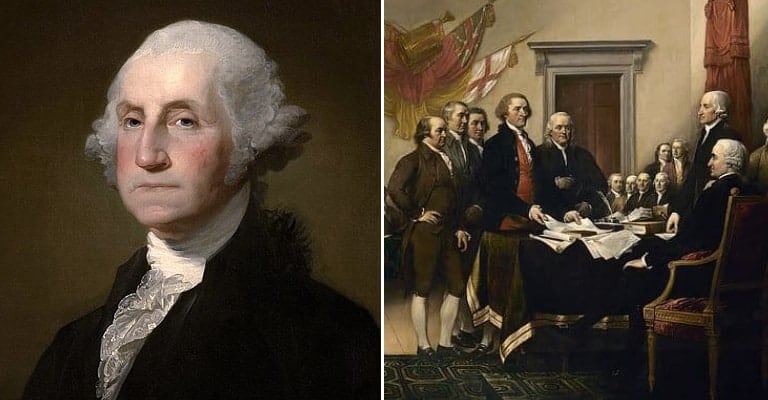

1. George Washington’s height has long been exaggerated

Some biographers have placed Washington as one of the tallest of the American Presidents, with estimates of his height ranging as high as 6′ 6″ and as short as an even 6′. Washington, in letters to tailors in London, described himself as being six feet in height and “proportionally made”. Yet in other letters, Washington frequently complained about the fit of his clothes, including overcoats, though the precise nature of his complaints – sleeves too short, breeches too full, etc – were not recorded in his letters. Other observers also wrote of Washington’s stature, and while it is safe to assume nobody measured him with a ruler, the consensus was that he was 6′ 2″ in height.

Upon his death, the doctors who had attended his final illness measured the corpse and reported it as being over 6′ 3″ and ½ inches, which led to some confusion among historians. Regardless of whether his own claim of being six feet tall or whether he was two inches taller is true is largely irrelevant, he was a big man for his day, both in height and in body mass. The average man reached a height of about five and a half feet in 1790. Many men were, obviously, much shorter, and Washington would have appeared to be of gigantic proportions, especially when mounted on horseback.