A raid is an armed mission by a relatively small group of attackers, prepared in secret with the hope of surprising and catching the enemy off guard, inflicting damage, then withdrawing before the adversary has time to react and bring superior numbers to bear against the raiders and overwhelm them. Raids typically seek to destroy vital enemy installations or goods, kill important enemy personnel, gather intelligence, loot, ransack, plunder, and otherwise confuse and demoralize the foe.

Usually, raids seek to harm the enemy without capturing or holding terrain, although that is not always so – sometimes a raid could be intended to capture a vital objective and hold it for a limited period of time until bigger and more heavily armed units can arrive to secure and consolidate what the raiders had seized.

Raiders could be specially trained warriors, such as special forces and commandos specially trained for raiding operations, or a normal military unit or ad hoc collection of non-specialty trained warriors assigned a special particular task.

Typically a feature of irregular warfare, raids could also be integrated into standard warfare when conducted to seize and hold an objective long enough for the arrival of follow-up regular military units.

Following are twelve of history’s most remarkable raids.

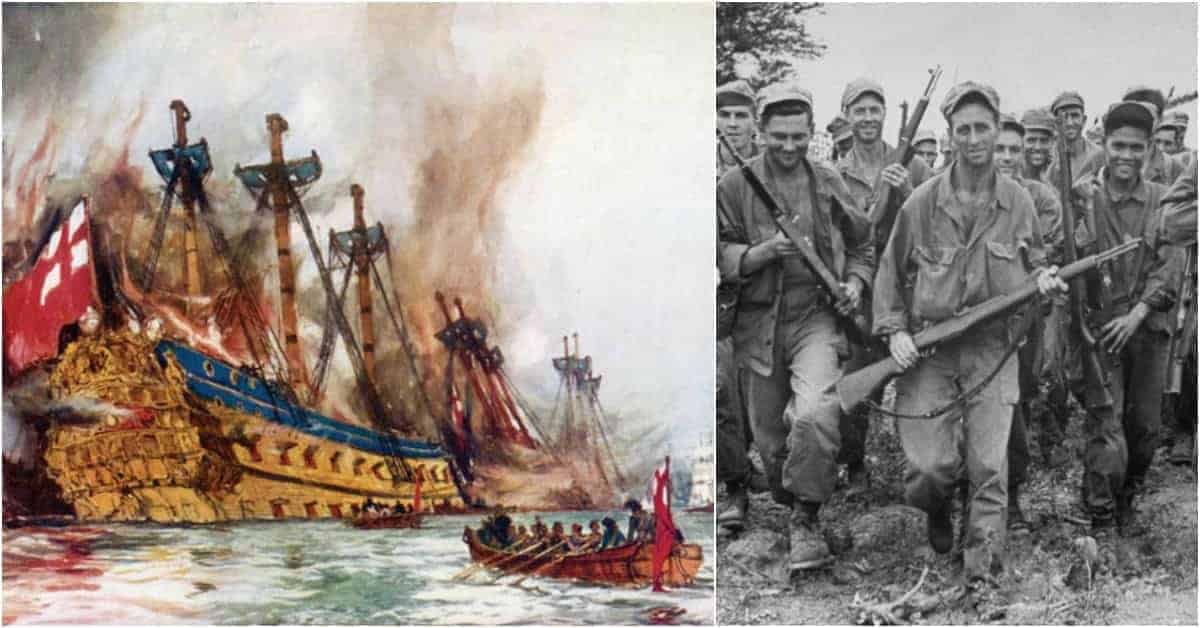

Raid on the Medway

The Raid on the Medway was a surprise attack by the Dutch navy which caught England’s Royal Navy off guard when it brazenly sailed up the Medway River in Kent to attack English battleships anchored in dockyards at Chatham and Gillingham. It took place between June 9-14th, 1667, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665-1667), and resulted in one of the most impressive victories in Dutch history.

Things had not been going well for England since the start of the Second Anglo-Dutch War in 1665, as it suffered first the Great Plague that ravaged London in 1665-1666, then the Great Fire of London in 1666. By 1667, England’s King Charles II was broke, unable to pay sailors, and desperately wanted out of the war. The Dutch, however, smarting from an earlier loss of the First Anglo-Dutch War, wanted to first inflict a crushing defeat on the English to even the score, which would then place them in a strong position to impose punitive peace terms on England.

To secure said crushing victory, the Dutch fleet, commanded by one of history’s greatest admirals, Michiel de Ruyter, entered the Thames estuary and bombarded and captured Sheerness at the mouth of the Medway. The attackers then sailed up that river, overcoming both a barrier chain stretched across its waters, which Dutch engineers overcame with ease, as well as fortresses along the way that were intended to protect the English battleships anchored at Chatham and Gillingham.

Upon reaching the anchored ships laid up in their dockyards, virtually unmanned and unarmed, the Dutch burned three capital ships and ten smaller warships, and captured and towed away as prizes two major ships of the line, including HMS Royal Charles, the flagship of the Royal Navy, named after the reigning king. In total, the Royal Navy lost 13 ships, while the Dutch lost none.

In addition to the serious material losses, the public demonstration that the English were unable to protect their own coastline, or their own fleet within their own borders, resulted in one of the greatest humiliations ever suffered by the Royal Navy and England. So great was the debacle that there were rife speculations about the imminent collapse of the monarchy, which had been restored only seven years earlier after a decade of rule without king during the period of the English Commonwealth.

Chagrined, broke, with a monarch seated atop a tottering throne, the English hurried to sign a peace treaty favorable to the Dutch the following month and exited the war.