It is generally known the allied effort to produce the atomic bomb during World War II bore the name Project Manhattan District. One of the most highly classified programs in American military history at the time, The Manhattan Project consisted of several efforts in the United States, Canada, and Great Britain, under the overall command of Major General Leslie Groves. Scientists, engineers, technicians, researchers, and trades specialists contributed to the effort. They built factories and towns to support and house them. Teams conducted counter-espionage operations. And the military wanted to know how advanced the German effort to build an atomic bomb had become. Finding out became the responsibility of the Alsos mission.

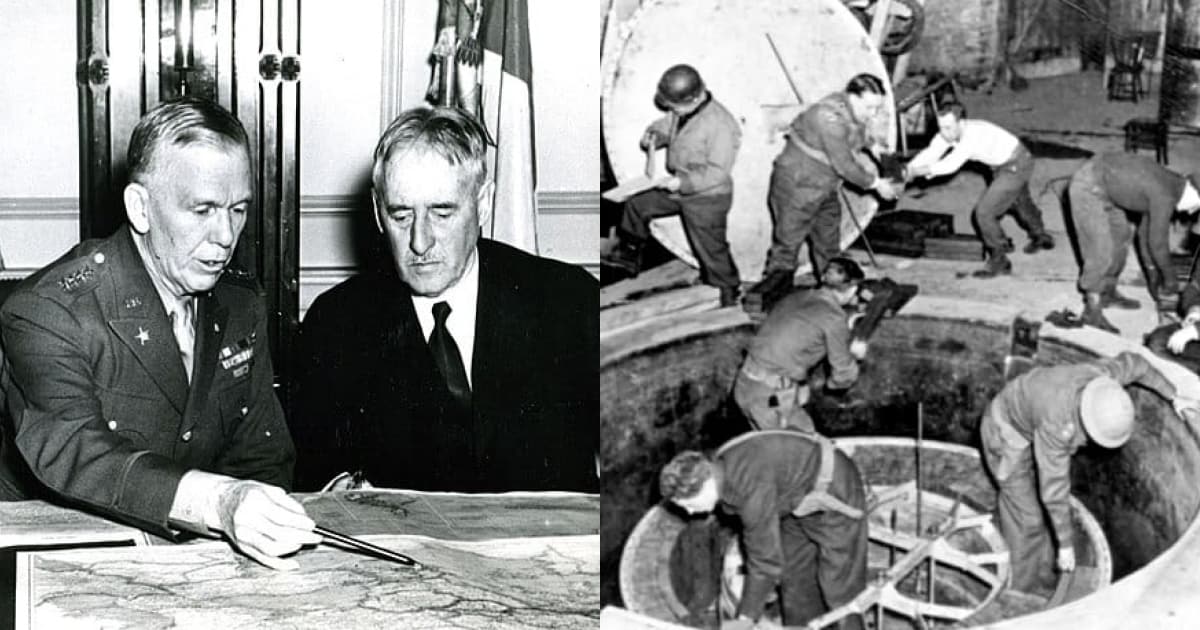

A little-known fact of the Manhattan Project is its program conducted in Europe, known as the Alsos Project. Also under the command of General Groves, Alsos formed to determine how much the Germans knew, and how close they were to a working bomb. The primary goal of Alsos was not to deter the German effort, but rather to keep the technology they had developed from the Soviets, with an eye toward post-war Europe. From 1939 to 1943, numerous European scientists working in the Manhattan Project despaired of the Germans developing a bomb first. In 1943 General George Marshall suggested the development of a special project, to be put in place in Italy under Allied occupation, later expanded into France and Germany. Here is the story of that program, known as Project Alsos.

1. The Americans assumed the Germans were ahead in developing an atomic bomb

Several of the scientists working in the Manhattan Project fled from Europe as Hitler consolidated power in the late 1930s. They came from other European countries besides Germany, among them Enrico Fermi, Leo Szilard, and Emilio Segre. The Europeans were of a mind that the Germans were ahead of the American effort, and expressed their concerns to General Groves. Groves informed George Marshall. Until the Allies invaded Italy, the Americans could do little to determine German progress, beyond intelligence obtained through spies and informants. Allied strategy assumed the Germans were developing an atomic bomb, and that the whole industrial complex of German-occupied Europe supported the effort. In 1943, with Allied troops occupying parts of Italy, General Marshall directed an effort be launched to ascertain as much as possible regarding the German program.

Marshall created the Alsos project via a memo in late 1943. “It is very likely that much valuable information can be obtained…by interviewing prominent Italian scientists in Italy”, he wrote. Marshall directed Groves to create a “small group of civilian scientists assisted by the necessary military personnel” to conduct the interviews. Marshall directed General Groves to personally select the civilian personnel, with the assistance of Dr. Vannevar Bush, and the support of military intelligence (G2). Groves selected Lt. Col. Boris T. Pash to command the Alsos Project. One of Groves’ first actions regarding Alsos was to protest over its name. Alsos, in Greek, means groves. The general expressed concern the name would draw attention to his role in the project. In the end, he decided to let it stand, believing changing it would draw even more.