Besides the death camps such as Auschwitz, generally referred to as extermination camps, the Nazis operated concentration camps throughout the Third Reich starting in the spring of 1933. Initially, the camps were used to imprison what the Nazis considered undesirables, such as political dissidents, homosexuals, Roma, and basically anyone else the Nazis didn’t like. At the time the Second World War started there were roughly 21,000 held in the camps. By the end of the war, there were more than seven hundred thousand.

Dachau, described by Heinrich Himmler as “the first concentration camp for political prisoners”, opened in March, 1933. It was mandated by the state that all communists were to be sent there, described as a necessity to ease the burden on the state prisons. The SA also opened some camps, which were taken over by the SS under Himmler the following year. Before the end of the war in 1945 with the collapse of Nazi Germany, well over three million people spent time in the German camps. Early in their existence, such as at Christmas of 1933, it was possible to be released from the camps as part of a pardon, or through rehabilitation, but as the war drew on those releases became rare. Here is some of what daily life was like in the concentration camps.

1. The difference between the concentration camps and the extermination camps

The original camps were built to house prisoners which the government deemed to be enemies of the state, which by Nazi definition included Jews. The early camps were built in Germany but after the conquest of Poland in 1939 construction began on camps in the German-occupied section, to house millions of Poles under Nazi control, and Jews and other undesirables from Germany. As the Nazis expanded westward, Jews from western Europe joined in the forced migration to the east. After the decision to implement the Final Solution, the construction of camps designed for the mass extermination of Nazi undesirables began.

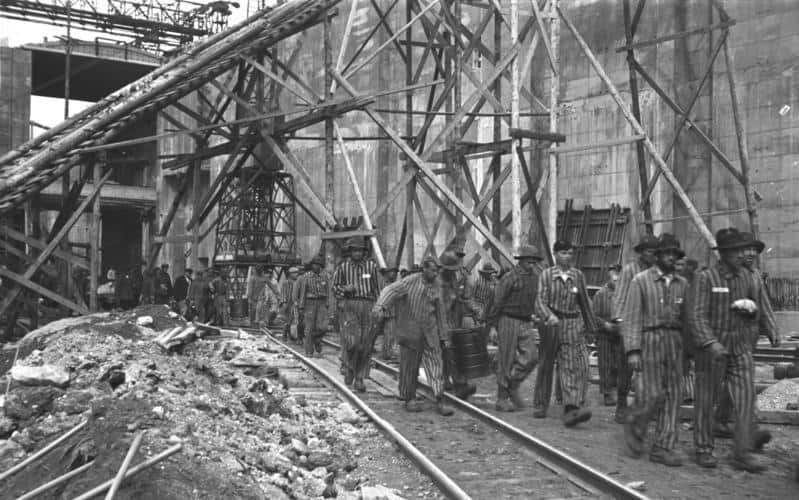

The existing concentration camps provided the earliest victims to the extermination camps, after which most of them were sent to the east directly from their homes or detention centers in Europe. At arrival, nearly all deemed unable to work were sent directly to the gas chambers. The concentration camps continued to receive new prisoners throughout the war, including some Russian PoWs, some other Allied PoWs considered of importance to the Nazis, state officials awaiting “trial”, those accused of treason, and others arrested within the confines of the Third Reich.