Music and crime go together like whisky and soda. Whether it’s hotel-smashing, womanising rock stars or bullet-dodging rappers, they all seem to be at it, and have been for a long time. After all, musicians lead something of an alternative lifestyle, in doing what they love for a living rather than getting a ‘proper job’, and so often find themselves falling foul of societal norms and taboos. Living (sometimes affluently) on the outskirts of civilisation, musicians often fall in with other types of outsiders: criminals, vagrants, rebels. The links are deep, and well-attested in the annals of music history.

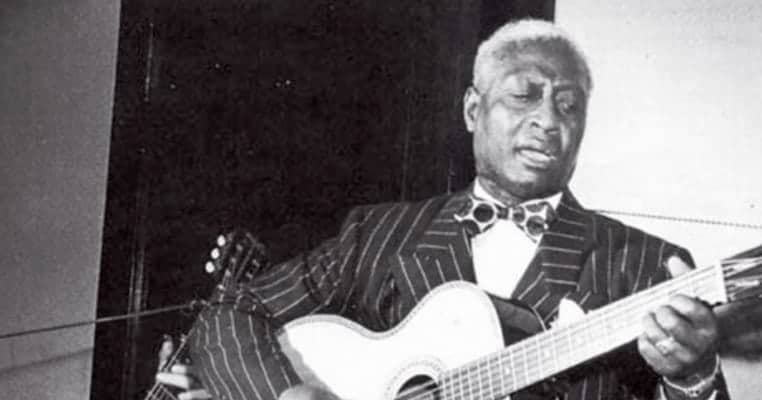

But amongst musicians who have flirted with the wrong side of the law, one man stands head and shoulders above them all: Leadbelly. A great bear of a man wielding a 12-string guitar, Leadbelly travelled through the racist and economically-desperate vista of the pre-WW2 United States, spending his time performing heart-wrenching blues and folk numbers to those in the know, and getting in fights. A convicted murderer, years-long veteran of chain gangs and some of the South’s hardest prisons, Leadbelly was the real McCoy, and in this list we’ll see what made him the most badass of all bluesmen.

20. Leadbelly grew up poor in the Deep South in the Jim Crow era

The man later nicknamed Leadbelly emerged from the womb as Huddie William Ledbetter sometime between 1885 and 1889. His unmarried parents, Sally and Wesley Ledbetter, lived on the Jeter Plantation in Mooringsport, Northeast Louisiana, and scratched out a hard and badly-paid existence. Nonetheless, for a black family of their era, the Leadbetters were reasonably well-to do. But, remember, this was the Jim Crow-era South, when laws brutally enforced racial segregation and ensured that African-Americans could barely eke out a living in constant terror of being convicted or lynched for any old crime white people dreamed up.

After years of hard-saving from his career as a sharecropper (backbreaking work in which a farmer has to give up part of their produce to their landlord), Wesley Leadbetter managed the unthinkable and bought his own farm. When Leadbelly was 5, the Leadbetter family moved to Bowie County, Texas: appropriately enough, as it later turned out, for it was a locale named after the famous knife-fighter, James Bowie. Like the Jeder Plantation, life for African-Americans was tough in Bowie: a US census of 1910 estimated that one-third of all black people in the county were illiterate.