Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Lusitania was on its 202nd Atlantic crossing when it was sunk by a German U-Boat in May, 1915. The event is widely believed to have impelled the United States into World War I, but it was another two years before America entered the war on the side of the Triple Entente. Many facts about Lusitania and its operation by Cunard have become mythologized since its tragic sinking, but the truth is the ship was built on a design which made it of value to the Royal Navy in the event of war. In 1982, after decades of denials, the British Foreign Office warned salvers of undetonated ordnance within the wreck of the ship.

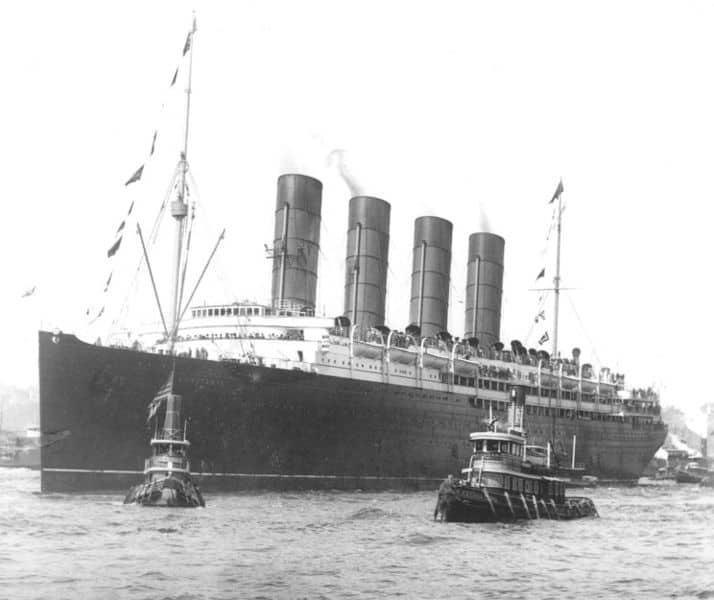

The ship was world famous before World War I. It was in service for less than a decade, but is known for its speed, its luxurious fittings and facilities, and its ability to accommodate over 2,000 passengers. The ship was among the most popular on Cunard Line’s Liverpool to New York route, supplemented by its slightly bigger and faster sister ship, Mauretania. What was largely unknown during the ship’s career (and remains largely unknown today) is that the vessel was built with funds subsidized by the British Admiralty, and was designed to be easily converted to an Armed Merchant Cruiser (AMC) in the event of war. Here is the story of RMS Lusitania and its sinking in 1915.

1. The ship was built to surpass its competition

At the beginning of the 20th century, the competition for passengers on the Atlantic was fierce. The best and fastest ships were a point of national pride in Europe. The Germans, Italians, French, and British built passenger liners which vied for the Blue Riband, the award for the fastest crossing. Bragging rights for the most luxurious accommodations, impeccable service, and convenience of schedules, were bandied about between the great shipping lines. All wanted to attract the richest and most famous passengers, using their names in news releases which served to imply the celebrities endorsed their ships over those of the competition.

First class passengers aside, it was in the lower classes where the lines made their bread and butter, in the lucrative passage of immigrants to the American east coast ports, particularly New York. The holds of the great liners also carried cargo, and their speed made them ideal for shipping material urgently needed elsewhere. Lusitania was designed and built with those facts in mind. It was built to be fast, to carry thousands of passengers, to offer luxurious cabins and services to the wealthy, and to carry cargo in its holds. In the first decade of the century, Europe was lurching toward war. The designers of Lusitania also considered the role which the ship would play in it when it came.