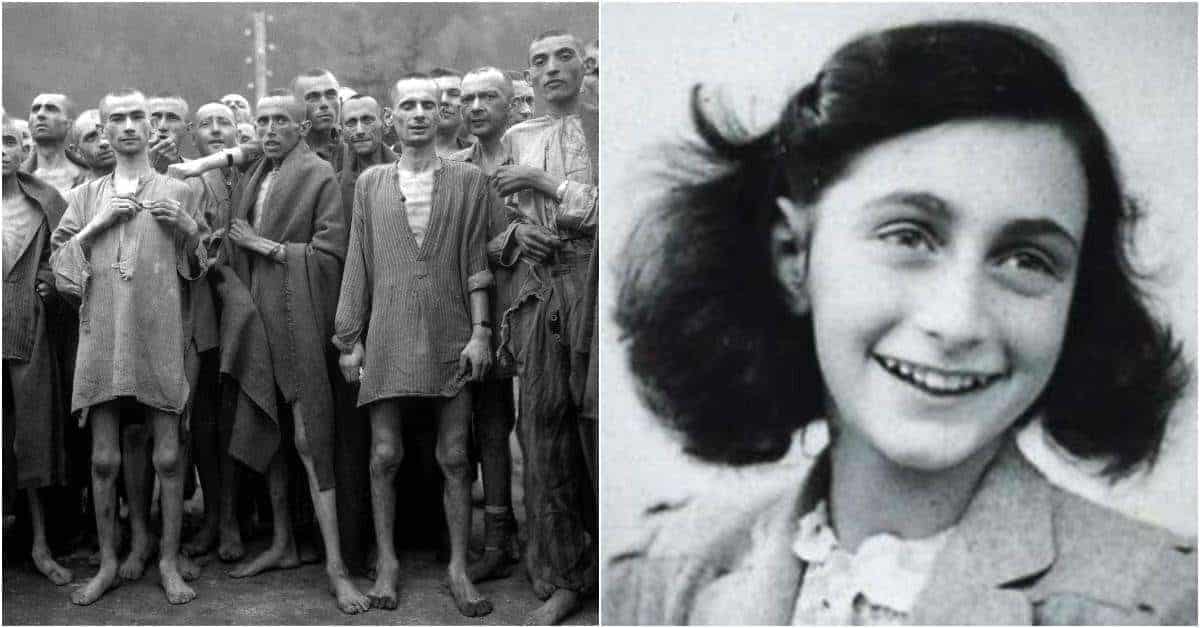

The Holocaust is one of the most devastating events in human history. The Nazis were unyielding in their persecution of Jews and anyone who didn’t fit into their idea of a perfect Aryan world. In his memoir Night, Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel stated that “hell is not for eternity.” For many Jews who lived in hiding during World War II, it was. They lived day to day, in fear of discovery, or worse. They endured horrible conditions to stay alive because that was better than the alternative of death.

As the Germans began to round up Jews all across Europe, murdering them on sight or sending them to labor or extermination camps, many people took their chances by surviving in hiding. Some hid in plain sight, and others relied on the kindness of their friends or complete strangers to survive.

These are some of the stories of people who lived in hiding and the people who risked their lives to protect them.

1. Tsvi Nadav-Rosler

When the Germans invaded Belgium, they started sending Jews to concentration camps. Tsvi Nadav-Rosler’s mother found a doctor who she managed to convince to name her children as having a contagious illness officially. Belgian officers came to their home in the middle of the night to bring the family for transport to the concentration camps. Tsvi’s mother managed to convince the officers that her children were sick and she needed to care for them.

The Belgian officers gave the family a fifteen-minute head start before more officers would come for them. Tsvi’s father remained behind with the first responding officers to give his family time to escape. When Tsvi’s mother left with her two children, they relied on resistance forces to help them find hiding places, and they moved from town to town quite often. The last place they hid was the village of Arbre, which was liberated in 1945.

After the war, Tsvi Nadav-Rosler studied graphic design at Antwerp’s Academy of Art. He relocated to Israel with his wife in 1959. He worked in graphic design for thirty-five years, and he managed the art department for Israel’s Educational Television. He is also an artist who documents his life in his paintings, including his time in hiding in Arbre.