War is an unforgiving line of work. A bad decision or an unlucky series of events can transform a formidable general’s reputation into synonym for tremendous failure. Europe, for example, trembled when Napoleon crushed the fearsome Prussian Army, but the petite empereur is best remembered for staging monumental snowball fights on the way back from Moscow. Because that’s what happens when a successful commander fails on the field of battle… usually.

Occasionally, a disastrous mistake, or three, does not ruin an officer’s glorious reputation, and this group of American military legends got a reprieve from history and a second chance they may not have deserved.

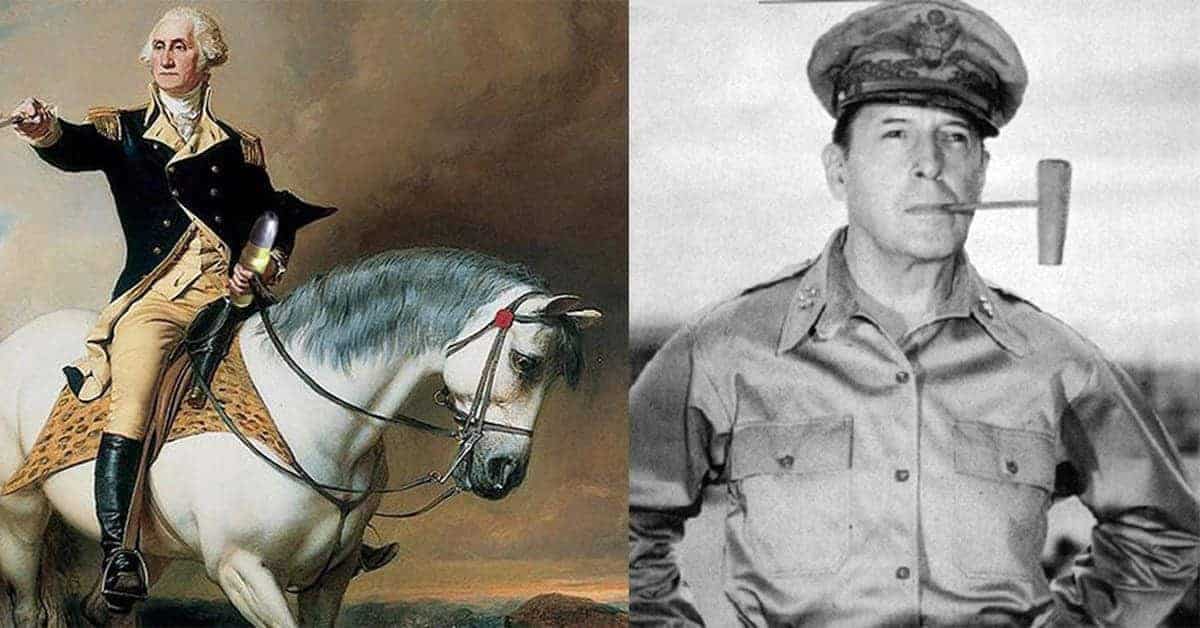

Douglas MacArthur – Battle of the Philippines (1941)

The General

Douglas MacArthur is a controversial figure in American military history, and his career includes some of the United States’ greatest triumphs and tragedies. He fought with distinction in World War I, modernized the U.S. Military Academy, and irreparably stained his honor during the Bonus Marches. Commander of sweeping World War II campaigns, overseer of Japan’s occupation, and crafter of the Korean War landing at Inchon, MacArthur was forcibly retired after testing the boundaries of civilian control over the military.

The Blunder

Beginning approximately ninety minutes after the bombing at Pearl Harbor, MacArthur was repeatedly warned to expect an attack. Despite these warnings, and official orders to launch an immediate offensive, MacArthur neither readied his defenses nor obeyed orders to assault Formosa. Thus, when Imperial Japan attacked, MacArthur’s ineptitude set the stage for the disastrous Battle of the Philippines, arguably the worst military defeat in United States history.

Battle of the Philippines

Shortly after the attack at Pearl Harbor, MacArthur was warned (informally) to anticipate an attack. MacArthur, however, chose not to alert his command. Brigadier General Sutherland, MacArthur’s chief of staff, passed the news onto General Brereton, commander of the Far East Air Force (FEAF) and MacArthur’s primary offensive weapon, but no other instructions. For unknown reasons, Sutherland would block Brereton from speaking to MacArthur for the next six and half hours.

General Brereton knew an immediate attack could catch Japanese aircraft on the ground, but only if his bombers reached Formosa before the enemy began their own assault. The general’s instincts were better than he realized. A thick fog bank had rolled over Formosa and delayed Japan’s offensive. An attack would have annihilated the larger Japanese air force on the ground. Unfortunately for the Philippines, MacArthur issued no orders of any kind.

Orders activating Rainbow 5, the offensive war plan, arrived an hour later. Rainbow 5 called for an immediate offensive using the FEAF exactly as Brereton envisioned. Despite receiving official orders, MacArthur did not issue instructions to Brereton or alert the base’s defenses. The hours dragged on. Brereton feared an imminent attack and ordered his aircraft aloft to prevent their destruction on the ground. Two hours later, MacArthur finally emerged from seclusion and reluctantly ordered attacking Formosa. Brereton ordered his aircraft to land and refuel. The fog bank that delayed Japan’s air assault, however, had dissipated while MacArthur dithered, and Japanese aircraft attacked while the FEAF refueled.

MacArthur’s complete and utter failure to ready his command for defense or to initiate an attack, as his orders dictated, crippled American airpower and laid the Philippines open to invasion. Excepting the escape of fourteen B-17s to Australia, the FEAF was completely destroyed. The reason for MacArthur’s lengthy indecisiveness and failure to follow orders is not known. Unlike the debacle at Pearl Harbor, there was no official inquiry into the devastating loss at the Battle of the Philippines. Years later, Sutherland and Brereton publicly blamed each other, and MacArthur issued a statement stating he recalled no recommendations to attack Formosa.

Insider Guide: Was General McArthur Really an American Hero or Overrated Narcissist?