Military strategists developed the concept of strategic aerial bombing during the interwar period in the 1920s and 1930s. Its proponents argued that destroying the enemy’s industrial capacity from the air would achieve victory at less cost in terms of men and equipment than defeating their armies in battle. Opponents pointed out the accuracy was questionable, results were often poor, and civilian casualties were unavoidable since factories and infrastructure were located in or near population centers. International law regarding strategic bombing from the air was vague, though the bombing of civilian areas occurred in China and during the Spanish Civil War.

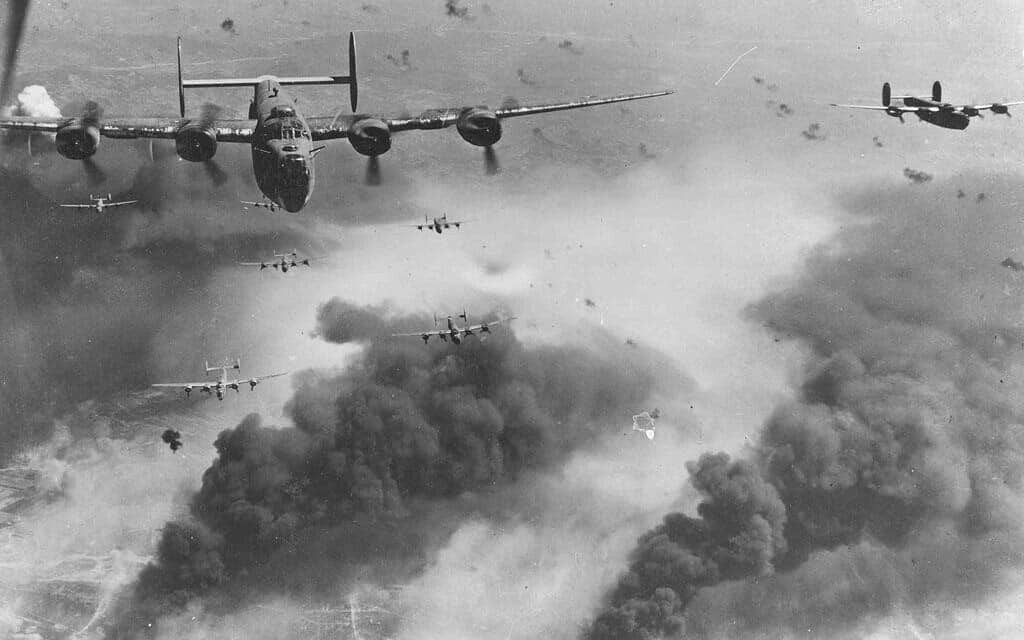

The United States and Great Britain developed bombers in the 1930s, including the Avro Lancaster and the Handley Page Halifax (Britain) and the Boeing B-17 and Consolidated B-24 (United States). Americans developed the policy of daytime precision bombing and their aircraft were heavily armed for self-defense. The British developed the policy of primarily bombing at night, when their planes were less vulnerable to fighter attack, at least early in the war. On September 1, 1939, American President Franklin Roosevelt cabled all of the belligerents, asking that aerial bombing in the new war be restricted to military targets. Britain, France, and Germany agreed to comply. The agreement was short-lived.

1. Germany bombed civilian areas in towns and cities during the invasion of Poland

The German Luftwaffe attacked civilian areas in cities and in some cases bombed small towns of little or no military value beginning on September 1, 1939. Some towns were selected for bombing purely to allow the Germans to evaluate the performance of their systems in combat. Towns with clearly defined street grids were selected to evaluate the precision of the German bombs. Afterward reconnaissance flights took photographs of the bomb damage for evaluation and correction. Civilian casualties in Poland were of no consequence to the Luftwaffe. In mid-September the French Air Attache in Warsaw cabled Paris the Germans were not attacking civilian areas, ignoring the evidence before him.

The French, who were allied to the Poles and obligated to support them, did nothing during the invasion of Poland other than protest. On September 3, British bombers attacked German facilities and ships at Wilhelmshaven, followed by bombing raids on Cuxhaven and Heligoland. At Heligoland on December, 22 British Wellington bombers attacked German Naval facilities, with 12 of them shot down by German fighters. The British made the attack in daylight, and the losses sustained reinforced their belief that night bombing was safer for their crews, though their accuracy was reduced. Daylight bombing in the face of the Luftwaffe and German anti-aircraft fire was deemed too dangerous.