“It is impossible to conceive a Country that promises fairer from its Situation than this of TERRA AUSTRALIS, no longer incognita, as this Map demonstrates, but the Southern Continent Discovered. It lies precisely in the richest climates of the World… and therefore whoever perfectly discovers and settles it will become infalliably possessed of Territories as Rich, as fruitful, and as capable of Improvement, as any that have hitherto been found out, either in the East Indies or the West.” Emanuel Bowen, on a map that speculated on the characteristics of Australia

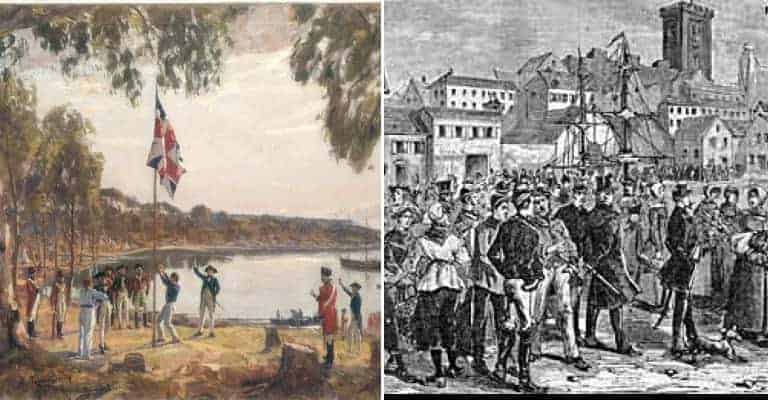

Australia Day, January 26th, marks the landing of the First Fleet at Botany Bay and the founding of modern, European, Australia. It was the moment at which one world began to end – that of the Aborigines, who had inhabited this great Southern land for well over 50 decades, unencumbered by the rest of the world – and the moment at which another began, an ersatz England in the Southern Hemisphere, populated by soldiers and prisoners locked a perpetual battle between technology, nature and social order.

The scale of the social experiment that was the colony of New South Wales is utterly inconceivable for modern readers. Most of those who went there had at that juncture progressed little further than their own narrow homes, this being a world still 70 years away from the first railway. The average Briton worked, lived and died within walking distance of where they were born. For these men (and it was predominantly men) the act of travelling to the other side of the world was akin to a modern person travelling to Mars. Moreover, the majority of those that made the journey did so against their will, case asunder by a society that had rejected them, and with all but no hope of ever returning. Plenty of those who were transported as convicts had barely avoided the hangman, but their death sentence was commuted to a more abstract form of permanent exile. They did not think that they would be sailing over the edge of the world, but for all that they knew about their new home, they might as well have done.

That these people – the vagabonds and their keepers, the outcasts and the outcasters – formed a community that survived at all is an amazing feat, and that the community that they formed has become one of the leading nations of the world is perhaps more amazing still. While those that already inhabited the land suffered immensely – Australia Day is rightly protested as Invasion Day by Indigenous Australians – the legacy of the First Fleet of convicts, soldiers and mariners is one that has created modern Australia.

Few, however, know quite the circumstances of their passage to the Antipodes, or quite how large a role chance played in the foundation of Australia. This Australia Day, let us go back and revisit their story with 12 things that most people do not know about the First Fleet.