Folklore is the memory of a people. Passed down orally over many centuries, even millennia, it reveals how ordinary people – often marginalized or ignored in written chronicles – interpreted the world around them. Snippets of folk belief can be seen in the written record of a certain period, but it was only in the seventeenth century that an effort to record oral tales was made. Charles Perrault (1628-1703) was the pioneer of this field and was the first to record timeless tales such as Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood. Similar work was undertaken by the Brothers Grimm in the nineteenth century.

Today, the work of these pioneering researchers has ensured that the old folk motifs and tales continue to bewitch and enthrall us. England is particularly rich in folklore and, having been colonized by people as diverse as the Celts, Romans, Saxons, and Normans over the centuries have inherited a cultural miasma that has produced a wonderfully complicated set of tales. Life for the peasants who passed these tales down the generations, however, was desperately bleak, and so many of the preserved tales are deeply unsettling and horrific. Keep the lights on: here are ten of the creepiest tales from English folklore.

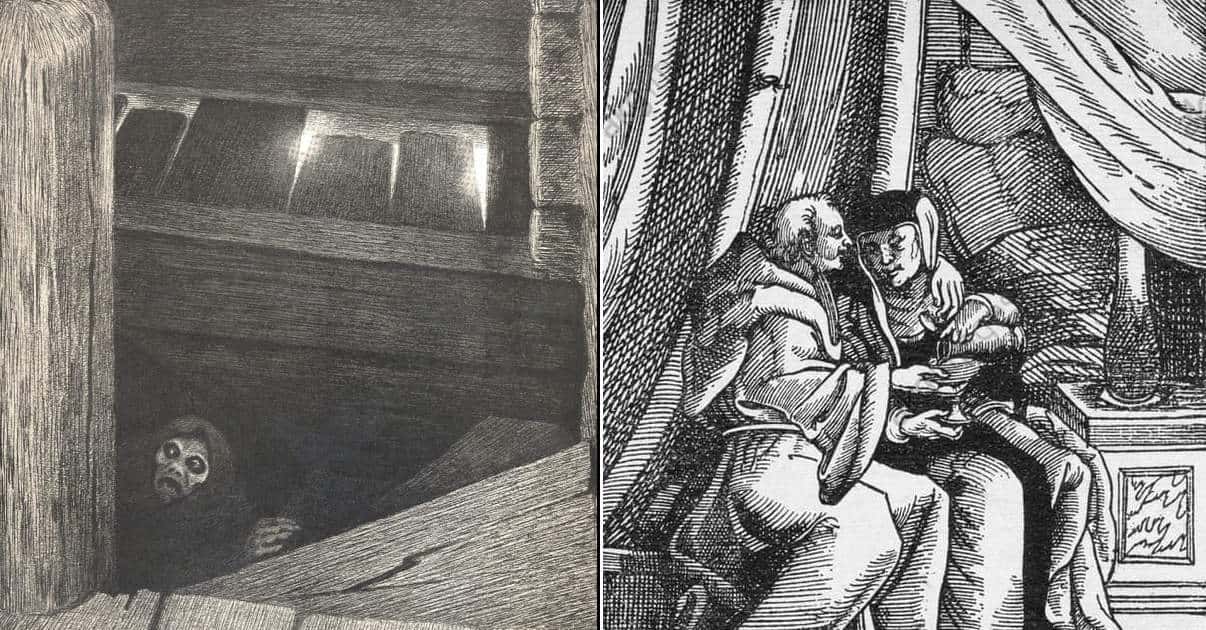

Black Dog

Across the country, tales are told of a hideous, shaggy-maned black dog with glowing red eyes which terrorizes lonely travelers and portends doom. It goes by many names, depending on the region in which it is found: Black Shuck and Old Shock (from the Old English scucca, ‘devil/ demon’), or Old Scratch (a folk name for the devil). Where it was found, the black dog had specific places that it haunted: the Reverend E. S. Taylor of Ormesby, writing in 1850, was alarmed to hear from his parishioners that a ‘black shaggy dog, with fiery eyes… visits churchyards each night’.

We will focus on the black dog’s most notorious appearance, in the Suffolk town of Bungay in 1577. A pamphlet on the hound’s deeds was written shortly after the event by Abraham Fleming, a prominent writer and clergyman. The story takes place one dark and stormy night, Sunday, August 4th, 1577. Then as now, such weather bred superstition and panic: ‘the roaring noise… ministred such straunge and unaccustomed cause of feare to be conceiued’. Though the people of Bungay were sheltered from the tempest at Mass, ‘the Church did as it were quake and staggar’ in the howling wind.

‘Immediatly… [there came] then & there present, a dog as they might discerne it, of a black colour’ in St. Mary’s Church. The congregation fell to their knees, praying to God that they be saved from ‘this black dog, or the diuel in such a likenesse’, but for two penitents it was no use: the dog ‘wrung the necks of them bothe at one instant clene backward, in somuch that euen at a moment where they kneeled, they straingely dyed’. After grabbing another man, whose skin instantly shriveled as if scorched, the dog disappeared as suddenly as it had arrived.

The church’s roof collapsed, but the dog’s killing spree was not over. It seems to have raced to nearby Blythburgh Church, where it sat on a beam where a cross once hung before running amok amongst the parishioners, killing two and scorching another. Burn-marks on the door of Holy Trinity Church, Blythburgh, are to this day attributed to the black dog’s fiery claws. But our story has one more creepy twist: in 2014, archaeologists found the remains of a 7-foot long dog at nearby Leiston Abbey dating from the 1500s. Is this tangible evidence for the legendary event?

Bungay has embraced the horrific event in more recent times, incorporating the black dog into its coat of arms, and some locals even have weathervanes topped by the beast. Explanations for the event itself range from outright credulity to the trauma of an especially fierce electrical storm. Fleming’s pamphlet offers a moralistic interpretation, as we might expect of a clergyman, leaving some to suggest that the tale was simply a piece of propaganda from the newly-reformed Church of England. The black dog is profanely commemorated in the song, Black Shuck, by The Darkness, who hail from nearby Lowestoft.