Probably the greatest con artists of all time remain unknown, for the simple reason that their crimes were never detected. But there are many known, having been caught at their schemes and brought to justice for them. Con artists are nothing new. Sir Isaac Newton himself proved a contemporary, William Chaloner, to be a con, a counterfeiter, and guilty of high treason. Chaloner operated one con in which he recovered stolen property for victims of theft, a task easy for him since he was also the thief who stole the property in the first place. His career came to an end when he was hanged for complicity in a lottery scam.

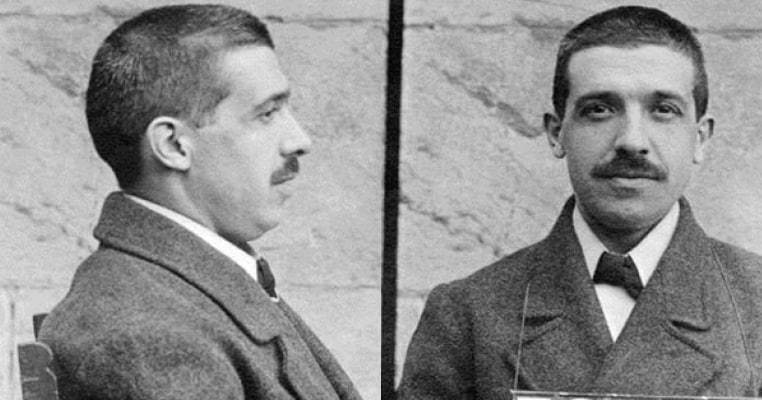

Some con artists become more or less honest men, offering advice on how to avoid the very scams which they formerly practiced. Frank Abagnale Jr, a former counterfeiter and con man, worked with the FBI, established his own financial security consulting firm, and had a motion picture made of his life as an international fraud and criminal. An Italian-American con artist and swindler developed a system for bilking people out of their money still widely employed today. His name was Charles Ponzi. Con artists remain a subject of fascination, almost of admiration by some, for the brazen nature of their schemes.

Here are ten of the greatest con artists in American history, omitting those who operated from the pulpit or the political stage.

George C. Parker and the New York Landmark Sites

An expression of skepticism in America, “If you believe that I’ve got a bridge to sell you”, is based on the oft-told story of con artists selling the iconic Brooklyn Bridge to gullible but well-heeled rubes. As unbelievable as it may seem the bridge has been “sold” many times, to many suckers, by many different fraudsters. The court records of both Manhattan and Brooklyn show that there were complaints filed and cases settled where victims were separated from their money and given an official-looking but counterfeit deed to the bridge. In one instance the new owners were arrested when they attempted to install toll booths on their recently acquired property.

George C. Parker was one such purveyor of property not his to sell, and by his own admission, he sold the Brooklyn Bridge several times, once even claiming that he sold the property an average of twice a week over several months. Parker bribed several ferry operators who delivered newly arrived immigrants from Ellis Island to Manhattan. The ferry operators were tasked with discovering who among the immigrants was carrying an amount of cash worthy of Parker’s attention. The ferry operators told their targets of real estate investment opportunities and directed them to Parker.

Parker wasn’t set just on selling the Brooklyn Bridge, though it was an easy deal since the immigrants had just encountered it upon entering the harbor, and at the time was the best-known landmark in New York. He also offered Grant’s Tomb for sale, and to interested parties, he intimated that he was not only the salesmen for the property but also the grandson of the former President. He was known to have sold the Statue of Liberty on at least one occasion as well as parts of Central Park, but his most profitable property was the Bridge, which he would show to his clients, explaining where they would be able to erect barriers and toll booths, giving them an immediate return on their investment.

Parker’s price for the Brooklyn Bridge varied widely, based in part on the accuracy of the ferrymen who assessed the wealth of the customer. On one occasion he sold the bridge for $5,000 and on others, he settled for as little as $75. Basically, the price of the bridge was whatever the mark had in their pocket. All deals were cash only. On occasion Parker was simply the sales agent, on others, he posed as the owner of the bridge or whatever piece of New York he was selling at the time. Parker managed to avoid being accosted by the victim on the majority of the occasions, but he was still well-known to the police of the city, as well as the courts.

On one occasion when Parker was taken in for questioning he waited until no one was looking, donned a policemen’s hat and coat and strolled out of the building. Eventually, he was arrested and held for trial, and on three different occasions, he was charged with fraud. The third time was the charm for him and he was sentenced to life in prison at New York’s state prison at Ossining. He died there after eight years in prison in 1936. During his career as a seller of New York landmarks, besides the Bridge and the Tomb, he was known to have sold Madison Square Garden, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, at least three Broadway theaters, and Battery Park.