The American Civil War did not exclude the American Indians of numerous tribes. The war’s divisiveness extended to the tribes, with some serving in the Union army, some in the Confederate, and some fighting against both. Tribes and whole nations chose one side or the other, and individuals opted to support one side while their families supported the other. As with the white American population, the war often pitted brother against brother. For the Indians, fighting in the white man’s war placed their homelands at risk of conquest.

Most of the Cherokee supported the Confederacy, unsurprisingly, since many Cherokee were slave owners. So were the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole and Creek peoples. When the tribes were relocated to the Indian Territory in the 1830s they took their slaves with them. Eventually, around 3 – 4 % of the southeastern tribes owned African slaves (many tribes used captives from other tribes as slaves as well). The issue of enslaved Africans and their descendants was as divisive among the tribes as it was in white America and lead to intratribal disputes and some actual fighting. Nonetheless, some Cherokee chose to support the Union, as did many southerners who were not slaveowners. Here is some of the complicated history of the American Indians during the Civil War.

1. The Trail of Blood on Ice

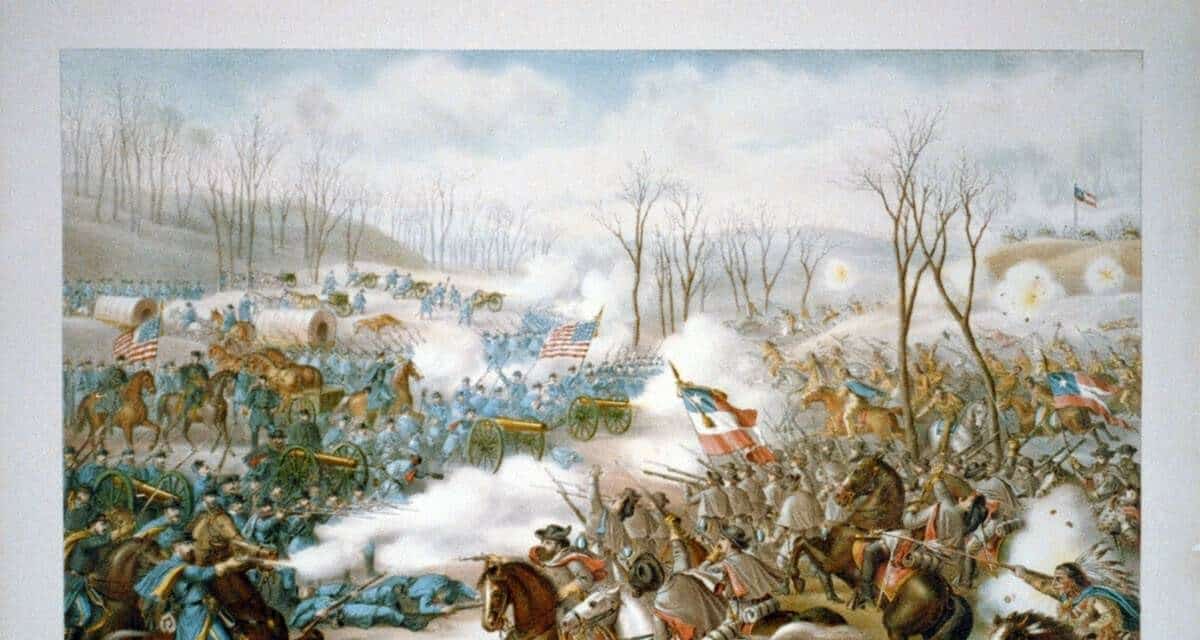

Following the secession of the Confederate states, most of the tribes in the Indian Territory leaned toward supporting the Union. That changed with the fall of Fort Sumter and the subsequent Confederate victory at the First Battle of Manassas. Leaders of the Cherokee, then the largest of the Indian nations in Indian Territory, lobbied for the territory to align itself with the Confederacy. Ancient tribal rivalries renewed. Several smaller tribes opposed the Cherokee leaders, and demanded the allegiance of the tribes to Washington. In November, 1861, a Confederate force entered the territory and clashed with some of the smaller tribes.

Opothleyahola, a Chief of the Upper Creek, decided to lead the pro-Union tribes to the safety of Union lines at Fort Row, Kansas. The Confederate troops under Colonel Douglas Cooper attacked them on their journey. The Trail of Blood on Ice was a series of battles between Confederate troops and their Cherokee allies against Opothleyahola and his followers, mostly Creek and Seminole. More than two thousand of his followers died as they fought their way to Kansas, where the survivors were mostly housed in refugee camps. Many, including Opothleyahola, died in them during the ensuing months. Their leader had survived the Battle of Horseshoe Bend during the Creek war, the relocation known as the Trail of Tears, and the Trail of Blood on Ice before succumbing to the harsh Kansas winter in 1863.