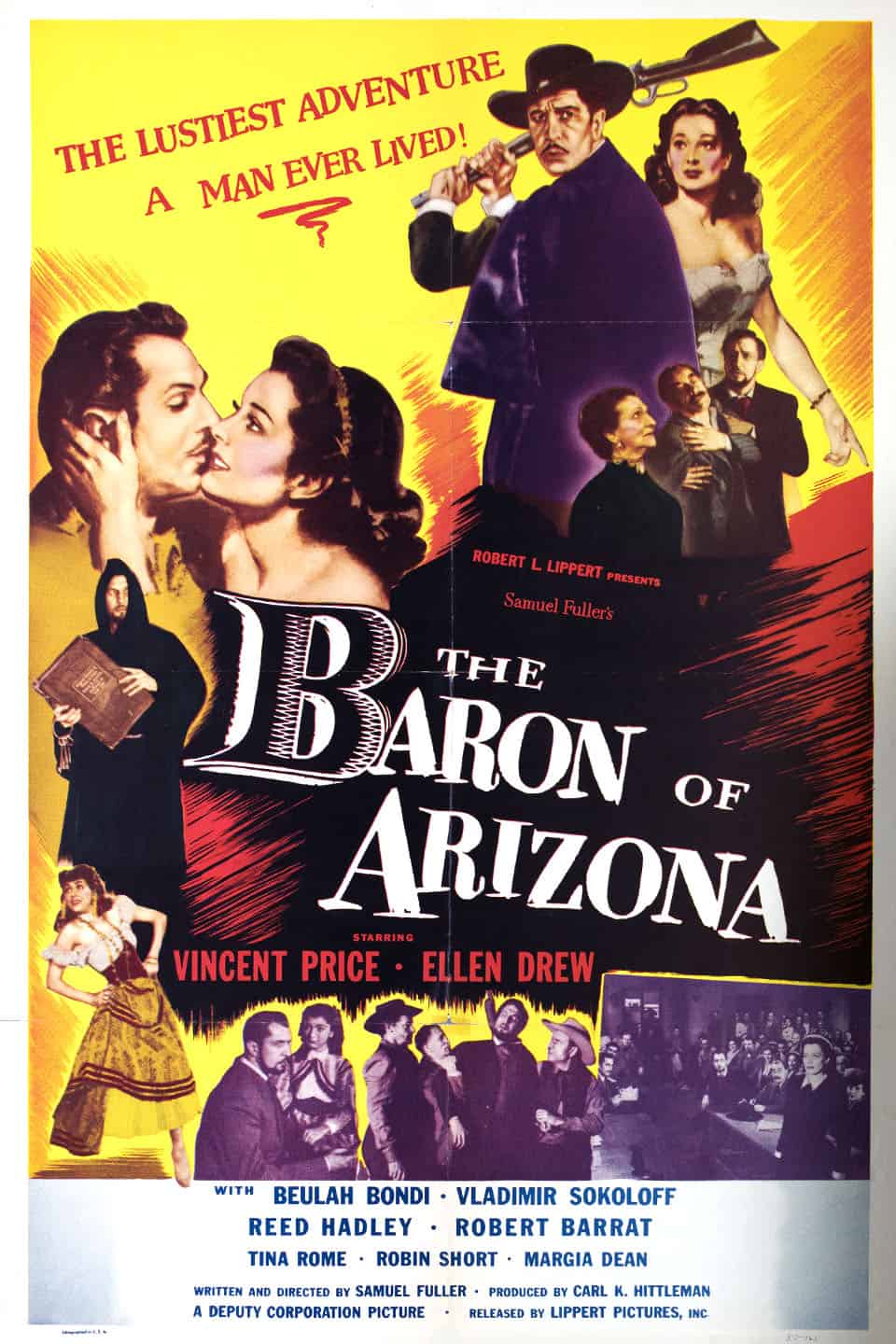

Back in the 19th century, a huckster laid claim to most of Arizona. In of itself, that would not be too astonishing: any random nutjob out there could claim to own Mars, but claiming it does not make it so. What is astonishing in this case is that thousands took the huckster’s claims of owning Arizona seriously enough to pay him for the privilege of living in it – including major business entities that paid him a fortune. For a while, even the US government considered paying him off. It just goes to illustrate that if one is brazen enough, there is no shortage of people who would accept what one claims – be it so batty – provided the claim is made with confidence. Following are twenty things about fascinating historic hucksters.

20. James Reavis’ Path to Becoming The Baron of Arizona: Getting Out of the Confederate Army

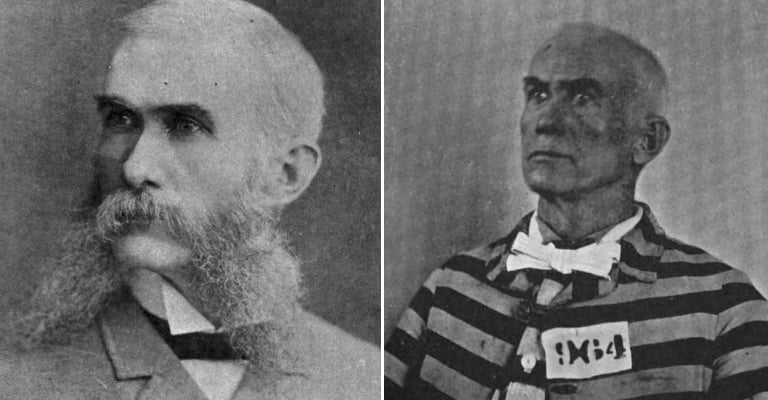

James Addison Peralta-Reavis (1843 – 1914), AKA “The Baron of Arizona”, might be the greatest conman you’ve never heard of. He defrauded thousands of people, and literally stole most of Arizona from its legal owners. Reavis’ father was a Welshman who arrived in the US in the 1820s, and his mother was a part Spaniard proud of her Spanish heritage. He grew up in Missouri, and during his childhood, Reavis’ mother fired up his imagination by filling his head with Spanish romantic literature. As a result, he ended up with grandiose notions of himself as a romantic hero in a melodramatic novel. It was reflected in his speech and writing, which was reportedly overly grandiloquent and bombastic.

When the Civil War broke out, an 18-year-old Reavis enlisted in the Confederate Army. However, he soon discovered that the tedium and travails of real soldiering were nothing like his romantic image of war. It was right around then that Reavis discovered he could make a perfect reproduction of his commanding officer’s signature. So he began issuing himself passes, with a forged signature, to escape the drudgery of soldiery and visit his relatives. When other soldiers noticed that Private Reavis was getting a whole lot of passes, he started a sideline business selling them forged passes. When the chain of command started getting suspicious and began investigating, Reavis finagled a quick leave, ostensibly to get married. He then promptly hightailed it out of Confederate territory, surrendered to Union forces, and even switched sides, serving for a while in a Union Army artillery regiment.