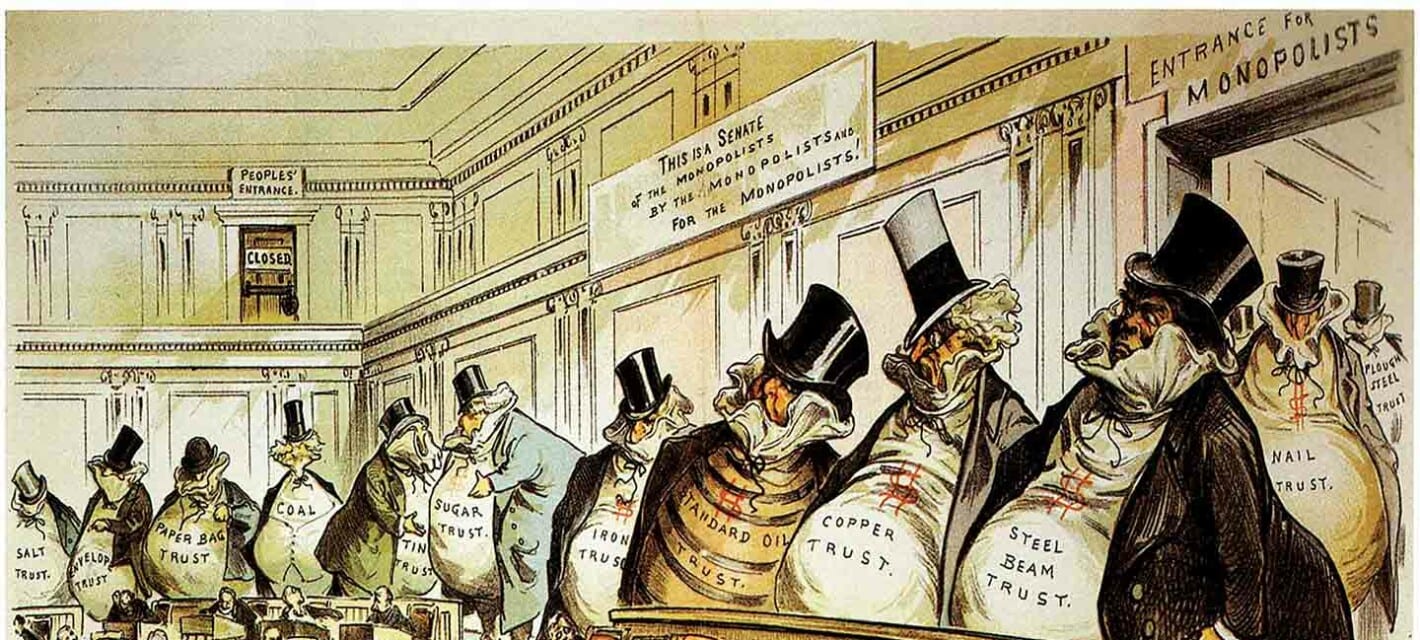

The Gilded Age, an 1873 Mark Twain novel that caricatured greedy businessmen and dirty politicians, lent its name to an era of great transformation. A period of gross materialism and massive political corruption, the Gilded Age was marked by the rise of a new class of ultra-rich entrepreneurs. Their wealth eclipsed anything seen before and allowed them to collect and pocket politicians by the dozen. The period was also one of extravagance and outlandish behavior. Below are thirty things about some fascinating but lesser-known Gilded Age facts.

30. The Gilded Age Was an Era of Great Changes

Just like the rapid pace of change in our world today bewilders many, the Gilded Age was an era of massive and revolutionary changes. Railroads knitted America together, the importance of factories, mining, and finance increased by orders of magnitude, immigrants arrived by the tens of millions, and cities and homes began to be lit and powered by electricity. Electricity had been around for some time, but it took Nikola Tesla (1856 – 1943), a Serb inventor who arrived in America with four cents in his pocket, to make the things that made electricity a part of everyday life. Among other things, he invented fluorescent lights, electric generators, the FM radio, spark plugs, remote controls, robots, and the Tesla Coil that is used to transmit radio and TV broadcasts.

Shortly after Tesla arrived in the US, Thomas Edison hired the brilliant but naïve new immigrant to redesign his electrical generators and perfect his light bulb, and promised him $50,000 if he succeeded. Tesla did, but when he asked for what he had been promised, Edison laughed it off and said: “Tesla, you just don’t understand our American humor. When you become a full-fledged American, you will appreciate an American joke“. After Thomas Edison screwed him over, Nikola Tesla took his talents to Edison’s greatest rival, George Westinghouse. Nowadays, alternating current (AC) lights up our homes and workplaces, and powers up our appliances through wall sockets. By contrast, direct current (DC), is relegated mostly to batteries. In the nineteenth century, however, the issue was undecided, and powerful interests fiercely competed to decide whether AC or DC would dominate the world. Tesla would decide it against Edison.