The Mexican – American War, known in the United States as simply the Mexican War, was a conflict in American history which Ulysses Grant referred to in his memoirs as, “…one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.” Grant was a veteran of the war, acquitting himself well in combat, and many of the officers of both sides of America’s Civil War received their baptism under fire while facing Mexican guns.

It was a war of simple conquest, with the United States acquiring the lands which became California, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado. It was a war which the United States provoked and prosecuted with determination, using a mostly volunteer Army by professional officers for the most part trained at the United States Military Academy. It was controversial before and after it was fought, and its aftermath heightened the debate over slavery in the conquered lands, where it had been abolished by the Mexican government. Under Mexico, the native tribes of the southwest were considered citizens, a right denied them by the United States. It was the capping triumph of manifest destiny.

Here are ten events of the Mexican War which made the United States a continental power, stretching from sea to shining sea.

Texas

When Texas was a Mexican state, its sparse population was subject to the depredations of the Cheyenne, which controlled a vast portion of the territory. Mexico opened the region to settlement by migrants coming from America, and motivated by the potential to create large estates Americans poured into the region. Disputes with the Mexican government led to Texas declaring itself independent in 1836, and the Texas Revolution, including the legendary Battle of the Alamo, established independence as fact. The United States recognized the Republic of Texas, though Mexico did not, and the border between Texas and Mexico remained in dispute.

In 1845 President James K. Polk, a fervent believer in Manifest Destiny, offered to annex Texas as the 28th American state. Texas entered the Union in December as a slave state, over the diplomatic protests of the Mexican government. Polk then offered to resolve the disputed border by purchasing the region between the Nueces River – which Mexico claimed was its northern border – and the Rio Grande, which was claimed by Texas to be its southern border. Mexico declined the offer. Polk responded by moving American troops into the disputed region, placing American outposts along the Rio Grande, in what the Mexicans claimed was their territory.

Polk’s motivation was not protecting Texas. He was aware of potential British Territorial ambitions in Upper California, and wanted the region for the United States. Following its independence from Spain, Mexico had withdrawn most of its military presence from Upper California (the region north of the Baja Peninsula) and the sparse settlements there were neglected by the Mexican government. President Tyler’s administration had suggested acquiring California by purchasing the port of San Francisco, but the Mexican government declined. The Polk administration was determined to stretch American territory to the west coast.

The troops Polk stationed in the Mexican territory established fortifications, an indication that their presence on Mexican land was intended to be permanent. At the same time an American expedition in California under John C. Fremont built fortifications in California. The Mexican government was in a state of disruption, and some Mexican leaders called for war with the Americans, while others argued forcefully against military action. By late 1846 the Mexican government was controlled by nationalistic factions, and American diplomat John Slidell, who had been attempting to negotiate the purchase of California and Nueva Mexico (the land between Texas and California) returned to the United States.

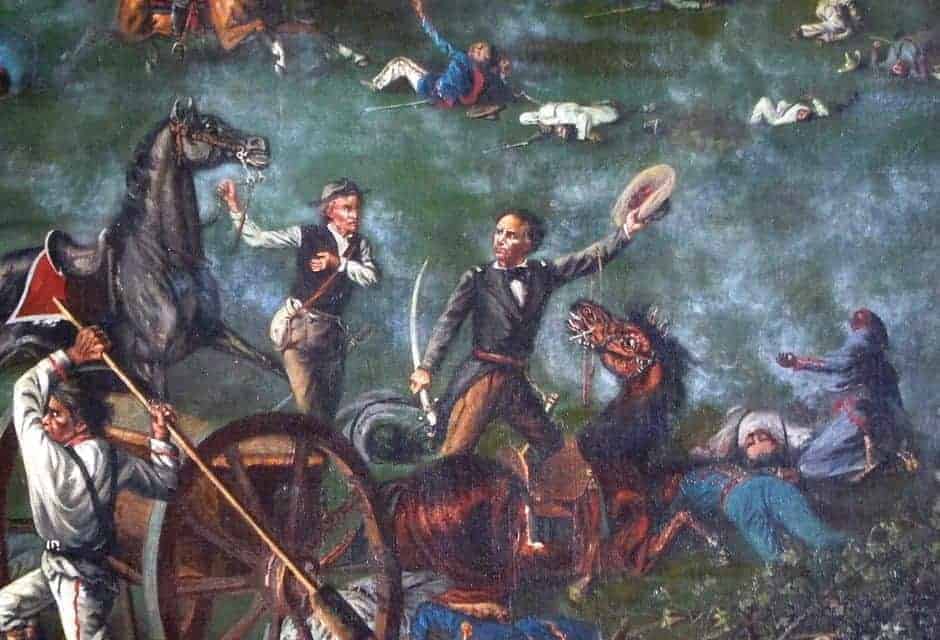

When the Mexican government demanded the US withdraw its troops to an area north of the Nueces River, American commander Zachary Taylor refused, and instead erected more fortifications along the Rio Grande. According to Ulysses S. Grant, a lieutenant with the American troops, “…we were sent to provoke a fight, but it was essential that Mexico should commence it.” In the spring of 1846, Mexican troops attacked an American patrol under the command of Captain Seth Thornton, which became known as the Thornton Affair. The following month, May of 1846, Mexican troops besieged Taylor’s garrison at Fort Texas.