Few, if any, events of American history were as divisive as the Civil War. Events which led to the conflict, the war itself, and its aftermath continue to divide the nation. Pervasive myths contribute to much of the misunderstandings surrounding it. Some of these myths are simply folklore. Others are deliberate revisions of history, seeking to rewrite the story of the bloodiest war in American history. How and why the war was fought, its conduct and the rebuilding of the nation in its wake are all shrouded with “facts” which have no basis in truth. Some are relatively harmless, despite their inaccuracy. Others continue to have a detrimental effect on society and politics over 150 years after the war ended. Arguments over the true causes of the war continue, despite the historical record clearly documenting what led to the conflagration.

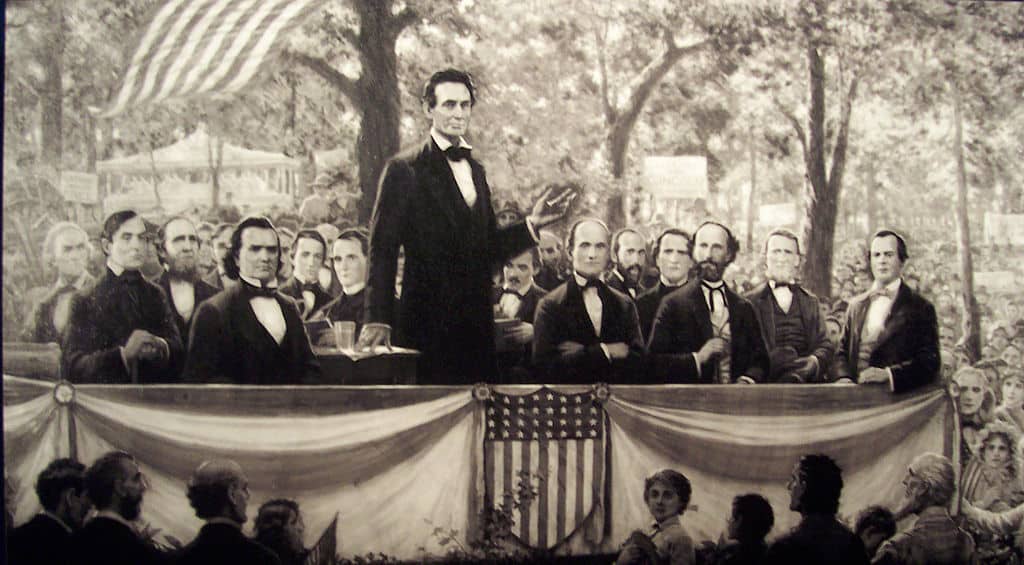

That the war ended slavery in the United States is unquestioned. But it did not establish racial equality. Even the man was known to history as the “Great Emancipator” did not agree the Black and White races were equal, at least not when the war began. Abraham Lincoln, in the sixth of his famous debates with Stephen Douglas (1858), asserted that if the two races were to live together one must be superior to the other. “I am as much as any other man in favor of having the superior position assigned to the White race”, he asserted. Lincoln’s views of racial equality did evolve during the war. In his last public speech, given just three days before his assassination, he announced he supported giving the right to vote to some, but by no means all, Black men. Here are some of the pervasive myths of the American Civil War.

1. The true cause of the war was the issue of states’ rights

An argument presented by apologists for the secession of the states which formed the Confederacy is that they did so to defend the rights of states as they were defined in the Constitution. The issue of states’ rights, rather than slavery, was the true cause of the war. They argue the Union violated the Constitution by threatening the practice of slavery in the South. At the time of secession, there were no bills in Congress to eliminate slavery. Lincoln announced, repeatedly and in clear terms, he had no intention of emancipating the slaves. Still, the Southern states, led by South Carolina, perceived the newly elected President as a threat. They voted for secession rather than accepting the results of the election of 1860. In their Declaration of the Immediate Causes, they made clear their primary reason for secession was the protection of slavery within their borders.

As other slave states followed suit they bound together, forming a central government they named the Confederate States of America. They created the Constitution of the Confederate States, which established a federal government. It denied the individual states the right to establish tariffs, print money, and import slaves from any foreign country. It also specified, “No bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed”. The Confederacy denied, through its Constitution, the rights of its member states to decide the issue of slavery at the state level, making slavery a federally protected institution. Those arguing the war was fought over states’ rights ignore this inconvenient fact. They also ignore another over the same issue, largely prevalent before secession. The southern states tried to deny states’ rights of their Northern neighbors before the war.