Carl Sandberg described Chicago in 1916 as the “player with railroads and the nation’s freight handle”. That description was certainly apt. Before the decline of passenger rail, which came in the aftermath of World War II, Chicago boasted no fewer than six passenger train stations. Its freight railyards were vast, including among them the railheads serving the Chicago Union Stockyards. Railroads were but a small piece of the transportation systems which served the Chicago area and fostered its growth. The waterfronts boasted piers and warehouses, supporting shipping on the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. The Calumet, Des Plaines, and Chicago Rivers all provided vital shipping routes.

Beginning in 1848, the Michigan and Illinois Canal supplemented the rivers. Goods from the Mississippi River region moved through Chicago to the east, across the Great Lakes and the Erie Canal to the east coast. The transportation system built a burgeoning city which was all but destroyed by fire in 1871, only to re-emerge as an industrial and commercial powerhouse fueled by the railroad boom. Later, roads for the new technologies of automobiles and trucks added to the city’s growth. Commuter systems to transport citizens and visitors developed. Here is how transportation built the city of Chicago, and continues to build it today.

1. Chicago was built upon an Indian canoe portage

The site of the city of Chicago was once an Indian portage connecting the Chicago River and the Great Lakes to the Illinois River, a tributary of the Mississippi. The marshy ground between North America’s two principal water systems carried Sauk, Miami, Potawatomi, and other tribes between the lakes and the central valley of the continent. Fur traders established a small settlement in the late 18th century. In 1803 the US Army established Fort Dearborn at the site. During the War of 1812 Indians allied to the British destroyed the fort and small community. It was rebuilt following the war, and the importance of the site as a trading center led to a planned community of lots.

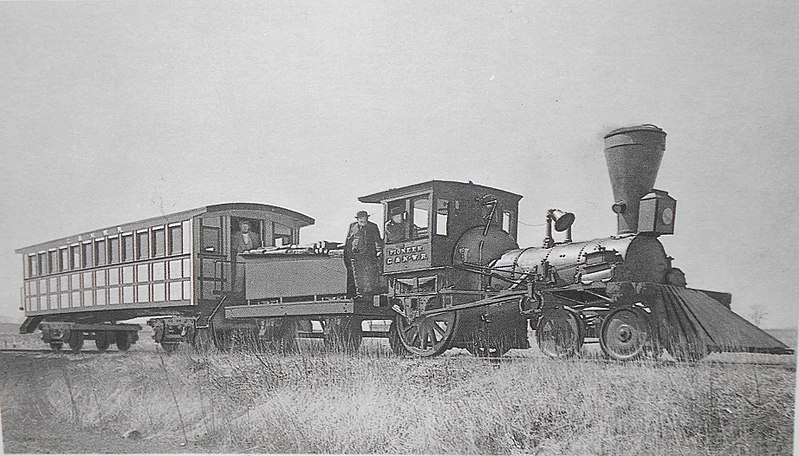

Robert de la Salle, one of the earliest European explorers of the region, first proposed a canal connecting the Mississippi River system to the Great Lakes. LaSalle declared the area “the gate of empire, this the seat of commerce”. Construction of the Michigan and Illinois canal began in 1836, and the community of Chicago grew from the workers on the project, and stores, shops, saloons, and inns to provide for their needs. Incorporated in 1837, Chicago became an inland port when the canal opened. By then a new means of transportation was shaping the country. Railroads, driven by increasingly reliable locomotives, connected Eastern cities. Chicago followed suit.