Deception and creative misdirection are vital elements of espionage and warfare. From planting fake information for foes to find and act upon, to lulling enemies into complacency before striking a sudden blow, history has had no shortage of schemes to mislead opponents by getting in their heads. Following are forty fascinating things about some of history’s greatest military deceptions, intelligence capers, and spy schemes.

40. WWII’s Most Important Corpse

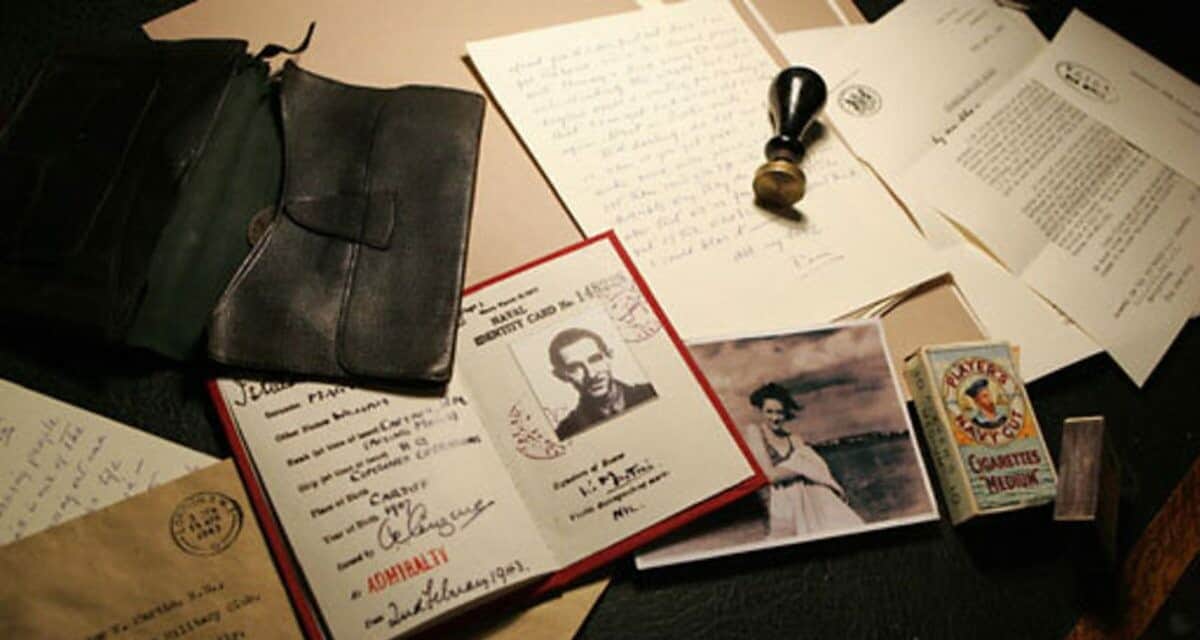

On the morning of April 30th, 1943, fishermen in southwestern Spain came upon a drowned man in uniform. The corpse was taken to the nearby port of Huelva, where documents on the cadaver identified it as that of Major William Martin, of the British Royal Marines. Looped around the major’s trench coat was a chain affixed to a briefcase. The British consul was informed, and he informed London of Major Martin’s fate via coded diplomatic cables.

That code had been broken by German intelligence, however. Reading the exchanges between London and the consul in Huelva, the Germans discovered that British higher-ups were extremely anxious to recover the drowned officer’s briefcase. So the Germans leaned on Spain’s fascist authorities to furnish them with the contents of Major Martin’s briefcase. The result was some of WWII’s most fascinating bits of espionage, deception, and counter-deception.