According to Sun Tzu, “all warfare is based on deception.” By keeping the enemy guessing about your intentions or capabilities, you can gain a serious strategic advantage. And the Allies in World War II knew this lesson as well as anyone. The history of the conflict is full of examples of war planners using daring and innovative methods of deception to trick the enemy. The Allies, in particular, often turned to unconventional techniques to counter the German war machine. And perhaps no operation demonstrates the lengths that the Allies were willing to go to when it came to deception as Operation Mincemeat.

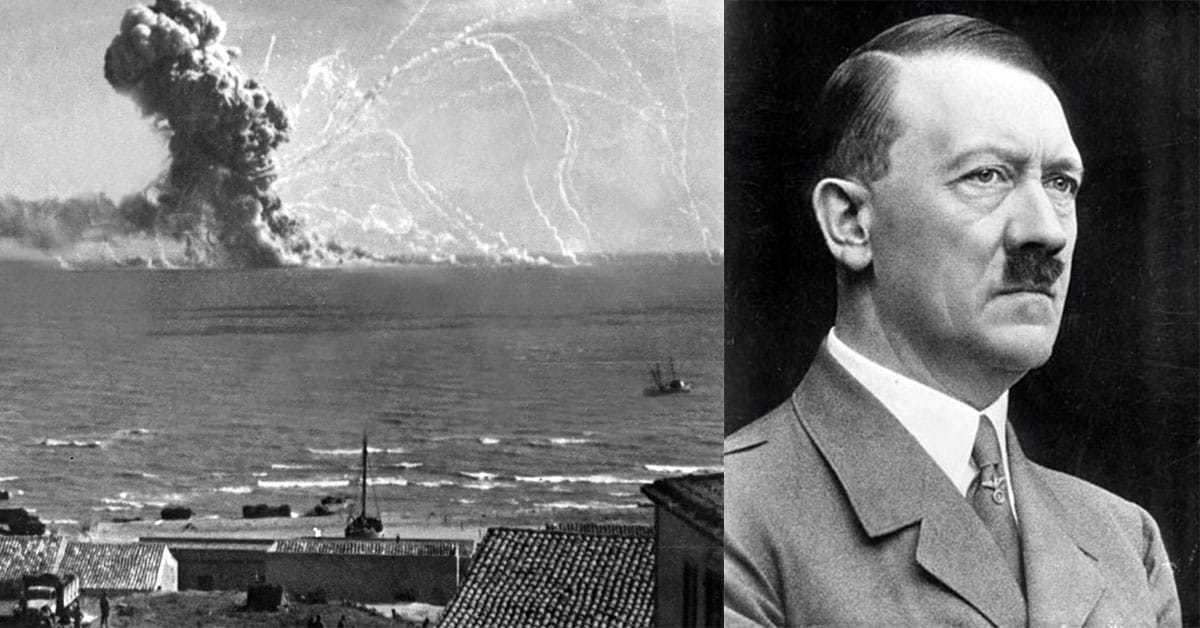

The basis of Mincemeat was a plan to deceive the Nazis into thinking that the Allies were about to invade Greece when they were actually about to invade Sicily. The Allies knew that it would be impossible to hide the fact that they were about to invade Southern Europe. So the planners of Mincemeat hoped instead to deflect attention away from the real target and thus divert Axis troops. But what set Mincemeat apart from other examples of wartime deception was that it was, by its own author’s admission, sort of ghoulish. And to understand just how unusual this plan was, consider what step one was: find a corpse.

Mincemeat was the brainchild of Ian Fleming, British spy and later author of the James Bond novels, and Rear Admiral John Godfrey, director of Naval Intelligence. Their plan was basically to find a dead body somewhere in England, one that no one would ask any questions about, and stuff its pockets with documents detailing the upcoming (and completely fictional) invasion of Greece. Then they would drop it into the sea near the coast of German-occupied Europe and hope that the Germans took the bait. The only problem was the obvious one: where do you get a freshly deceased body without raising any suspicions? Luckily, the planners would soon get a break thanks to a man named Glyndwr Michael.

Glyndwr was the son of a coal miner from South Wales and had spent most of his life drifting from place to place. Finally, in 1942, he ended up in King’s Cross, an industrial part of London. Michael began living in an abandoned warehouse, where, one winter night, either fed up with everything or perhaps just desperately hungry, he ate a piece of bread smeared with a fatal dose of rat poison. The next morning, his body was picked up and sent to the local morgue where the director, doctor Bentley Purchase, realized he had finally found the body he was looking for.

British Naval Intelligence officer Ewen Montagu had approached Purchase a few months before with the plan for Mincemeat and asked if Purchase could help find a body to use. Once Michael, a man who was recently deceased with no relatives to ask questions, turned up in his morgue, Purchase called Montagu who came by to inspect the body. Despite some reservations about the condition of Michael’s body, Montagu agreed that he was a suitable candidate and the corpse was soon tucked away and frozen to keep it fresh while Montagu started creating its new identity.