Female warrior heroines appear in the myths and legends of numerous ancient cultures, sharing many similarities among their tales. British mythology includes Queen Cordelia, for example, the daughter of King Leir, immortalized in Shakespeare’s play, King Lear. In her legend, she led her father’s army against those of her sister’s husbands, restoring her father to his rightful throne. After his death, she ruled Britain until her sister’s sons defeated her in battle and imprisoned her. She died a suicide in the legend. There is no historical evidence she ever existed. The story began with Geoffrey of Monmouth, who also largely created the myths of King Arthur and Merlin.

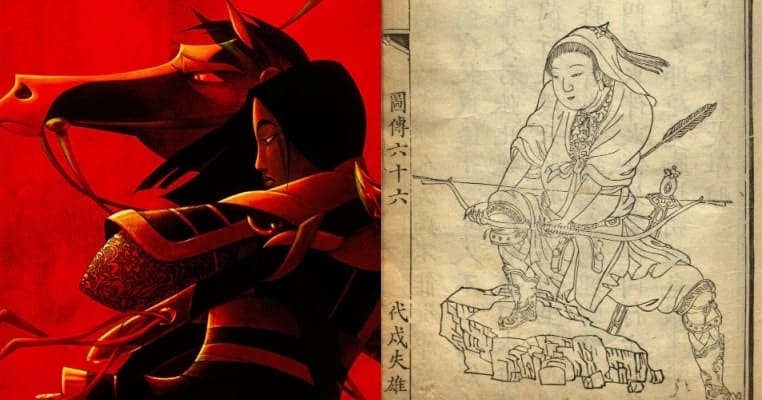

The same is true of a Chinese female warrior and heroine, Hua (sometimes rendered Hoa) Mulan. Mulan’s historicity is considered doubtful, since she first appeared in poetry and song, while contemporary historical documents failed to recount her story. Her legend has lasted for centuries, appearing in silent films in the 1920s, motion pictures with sound in the 1930s, television programs, children’s books, and more recently animated and live-action films. Yet beyond the artistry of balladeers, poets, and scriptwriters, there is little in the historical record to verify either her existence or her legend. Here is the legend of Mulan, and how it has changed over the centuries.

1. The Ballad of Mulan

Mulan’s first known appearance, as well as the legend associated with her, came during the period of the Northern Dynasties, sometime between 380 and 580 CE in the Ballad of Mulan. Likely written following a period of warfare between the Tuoba people of the Northern Wei and their enemies, the Rouran, the ballad grew popular during the ensuing Tang Dynasty. In the song, Hua Mulan laments that she has “no one I think of, there is no one I long for”. She learns the Emperor (Khan) called for conscription, and in the absence of an older brother to take the place of her elderly father, she decides, “…to buy a horse and saddle, to go to battle in my father’s place”.

The ballad implies her parents knew of her deception when she disguised herself as a man and entered the army. It describes “ten thousand miles she rode in war”, which continued for 12 years. When the war ends, the Khan thanks her for her meritorious service, after which she asks for only the “swiftest horse, to carry me back to my home town”. Once home, accompanied by the other troops from her town, she removes the armor, and fixes her hair and make-up. She appears before her astonished brothers-in-arms as a woman, having successfully disguised herself for over a decade in their company. The ballad ends with the verse, “But when the two rabbits run side by side, how can you tell the female from the male?”