There is nothing like a stroll around the New Orleans French Quarter. The historic buildings line the streets boasting delicate Spanish-style wrought-iron railings. Breathing in, visitors guess what that wonderful mix of smells might be wafting from restaurants; is it authentic gumbo? Beignets? Etouffee? And with a turn of the head, a different powerful odor. Is it coming from that guy passed out in the street in a pool of booze-induced vomit?

Perhaps body odor from the crushing crowds vying for beads. New Orleans French Quarter is a hotbed of rowdy revelry, drunken debauchery, and tourist traps. But the modern tourist party scene is just the latest chapter in the sordid history of the French Quarter. Since the earliest days of the city, the French Quarter has been a hotbed of scandal and story, some fact, some fiction, some a curious blend of both that propels the district into legend.

The Early French Quarter

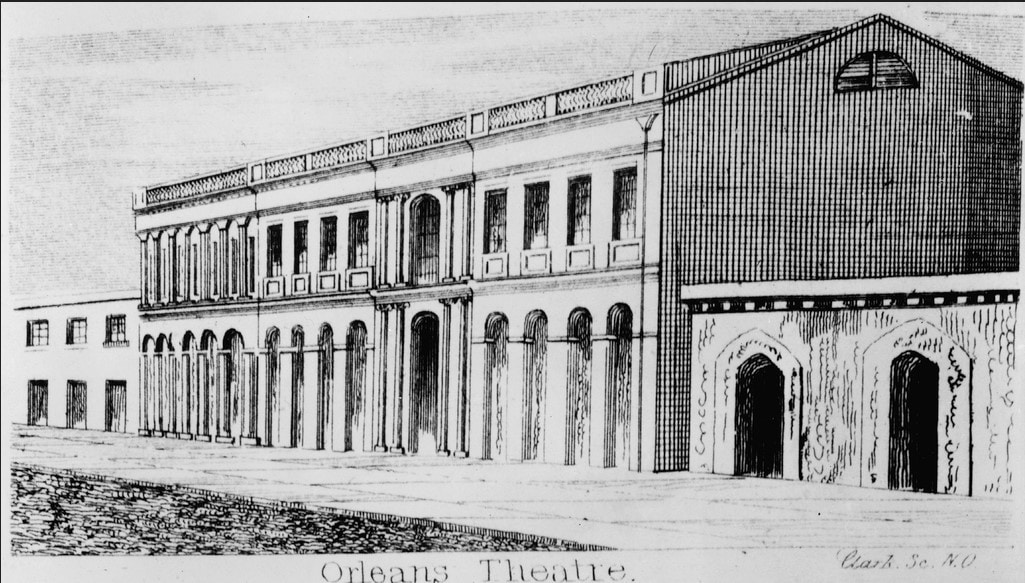

The French Quarter’s history began in 1718, when Jean Baptiste Bienville, governor of the Company of the Indies, founded a small military community along the swampy banks of the Mississippi River delta. He named the small development after the Duc d’Orleans in hopes of earning favor in the royal court. French rule would end in 1762, after King Louis XV gave the Louisiana territory to his cousin Charles III of Spain.

Spain ruled the area for forty years, leaving a lasting mark on the architecture and culture of the district. Fires gutted the area in 1788 and again in 1794, but the population would rebuild. Over the years, residents suffered yellow fever, cholera, and malaria. Despite these plagues, they came back, stronger than ever. In 1803, New Orleans was part of the massive land deal, the Louisiana Purchase, and it officially became part of the United States.