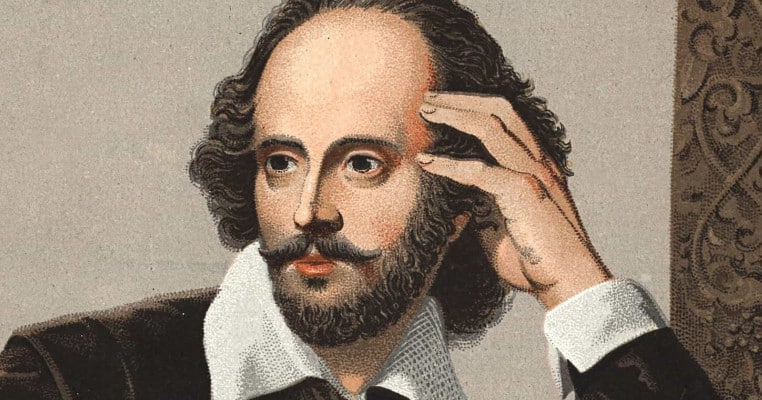

Marriage is a subject that cultures have hotly debated since antiquity. During Elizabethan England, William Shakespeare watched these social events unfold around him and used it to his advantage. Shakespeare’s work reveals ideas relating to marriage, romance, and love throughout early modern Europe during the Renaissance specifically in Elizabethan England. His works of Romeo and Juliet, Much Ado About Nothing and Taming of the Shrew will be subjected to an in-depth analysis of love, courtship, and marriage that was common during the English Renaissance period.

From the latter of the twelfth century until 1563, Catholic Europe marriage was per verba de praesenti- speaking words that they are married at that moment in time. This way of marriage was in place for Protestant England from the Reformation until 1753. The condition of these marriages was that both bride and groom must consent to the marriage. During this time, God was the only witness needed to bind a marriage together legally. Towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign, canons of the Anglican Church were reissued. These were restrictions that full marriage was legal only by having a ceremony in a church, with a priest, banns read, a license obtained in advance, and with parental consent if the bride and groom were minors.

Shakespeare witnessed these changes in marriage as he, himself, wrote plays that inducted those ideals. Along with current social and political trends of his age, Shakespeare took some ideas for his plays from classical antiquity. He was a Renaissance humanist who studied Roman and Greek works. He turned to antiquity for many of his works including Julius Caesar and The Rape of Lucrece. Another major literary area he drew from was European and English fiction that were mostly written in prose or verse.