Most people are familiar with the historical exploits of Alexander the Great. After unifying Greece, he set about defeating the declining Persian Empire and conquering lands to the East, marching to the ends of the known world as far as the Hindu Kush in northern Pakistan. As a military tactician, he inspired the likes of Caesar, Hannibal, and Napoleon. As an imperialist he lay the groundwork for the Romans, who sought to replicate his feats while avoiding his failures (Alexander’s failure to consolidate his empire resulted in hundreds of years of civil war after his death).

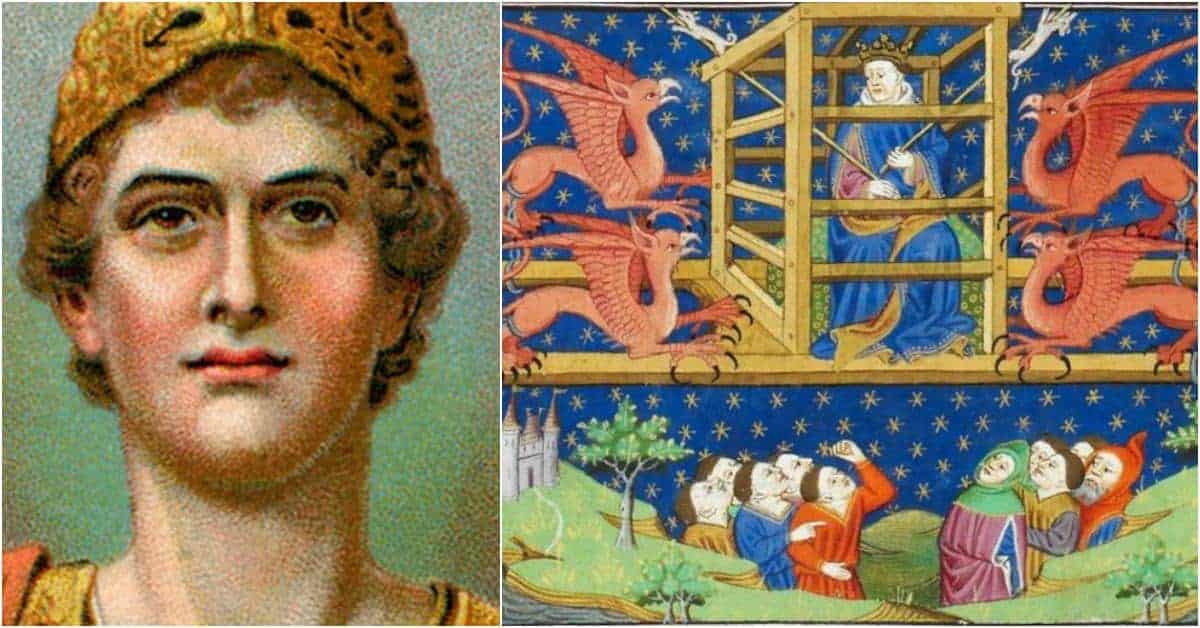

Fewer people, however, know about the legendary Alexander. This Alexander was less the great general and more the philosophical protégé of his tutor Aristotle. He dived to the depths of the ocean in a glass bell, searched for the elixir of life, and debated philosophy with naked ascetics. He was also a religious figure, a key character in many Jewish, Christian, and Islamic writings as a prophet, a sacred hero, and a messenger of God.

The legendary Alexander has had just as much, if not more, currency throughout the history of the last 2,000 or so years than the historical one. And traces of him can be found in some unexpected places: from the Old Testament to the Qur’an to philosophical texts and adventure novels of the Middle Ages and Early Modern period. Here are nine of the most surprising.

Alexander in the Old Testament

Alexander’s occupation of the Levant was marked by brutal violence. He spent seven months between January and August 332 BC besieging the city of Tyre. Having finally subjugated it, he had around 3,000 of the city’s defenders crucified on its beach. He then moved onto the Gaza, and after capturing the city he ordered for hooks to be dug into the ankles of the man who had commanded its defense. In imitation of Achille’s mythological desecration of Hector’s corpse, the Macedonian king then had the unfortunate commander tied to his chariot and dragged to his death.

After subduing Gaza, Alexander departed the region and moved on to Egypt. But in 331 the Samaritans rebelled, burning alive the Macedonian satrap he had installed in the province. The king returned to the Levant to take vengeance. He hunted down and executed the leaders of the revolt before trapping other participants in a cave in Wadi Daliya and suffocating them with smoke.

Because Alexander’s barbarity left a lasting legacy, it’s little surprise that they appear in some of many of the scriptural texts composed in the area. The Macedonian king appears several times in the Old Testament, firstly in the First Book of Maccabees (1:1). Written in about 103 BC, it describes how Alexander “captured fortified towns, slaughtered kings, traversed the earth to its remotest bounds, and plundered innumerable nations” before going on to moralize how his “pride knew no limits.”

The Macedonian monarch also appears, allegorically rather than by name, in the Book of Daniel (8.5-8, 21-22), a text written around 165 BC. The passage in question narrates the Greek conquest of Persia. It describes a “he-goat from the west” who appears in the area and, in a great rage, charges at a “two-horned ram”, knocking it to the ground and trampling it to death.

That the he-goat represents Alexander (and the two-horned ram Darius II) is clear for two reasons. Firstly, the Book of Daniel mentions a prominent horn between the he-goat’s eyes. Even during his lifetime, Alexander was often depicted with horns, owing to the fact that he claimed his father was not Philip but the horned god Zeus Ammon. Secondly, the prophecy ends with the goat becoming “very great” but his horn breaking off at the height of his powers—a metaphor for the Macedonian’s premature death in Babylon at the age of 33.