The US Civil War was the last conflict in which significant numbers of American children were utilized as soldiers: it is estimated that a fifth of all military personnel in the Civil War were under 18, and that more than 100,000 soldiers in the Union Army alone were 15 years old or less. There were even cases in which children as young as 8 were put in uniform.

For the most part, child soldiers in the US Army were utilized as drummers, buglers, cooks’ assistants, nurses, orderlies, general gophers, or put to work in other non-combatant positions. However, during the storm of shots and shells as battles raged, Civil War child soldiers were frequently just as exposed to bullets and artillery as were the grown men on the firing line.

In the US Navy, children frequently served as “powder monkeys” in warships. Tasked during combat with rushing gunpowder from magazines to canons, they were just as exposed to danger during the action as were all other sailors aboard ship, regardless of age. Indeed, considering that they were scurrying about carrying sacks of gunpowder liable to go off if it came into contact with any spark or shard of flaming timber or scorching shell fragment, the little powder monkeys might have been at greater risk than the rest of the crew.

On land, children being children, full of curiosity and frequently heedless of and insensate to danger and mortal risk to life and limb, there was no shortage of instances in which child soldiers snuck off to the firing lines in order to see for themselves the excitement of battle from up close, or even picking up rifles and rushing into the maelstrom, fighting and dying alongside the adults.

Although there were age restrictions on official enlistment in the ranks – in the Union, enlistees had to be over 16 – such restrictions were usually honored more in the breach than in the observance. For example, many an under-aged Northern boy, eager to enlist, had little trouble in finding a recruiter willing to sign him up so long as he was willing to put one hand on the Bible, raise the other, and swear that he was “over 16”. Some children ingeniously reconciled their consciences with the lie by writing the number “16” on a piece of paper, sticking it to the bottom of a shoe, thus enabling them to honestly swear that they were “over 16”.

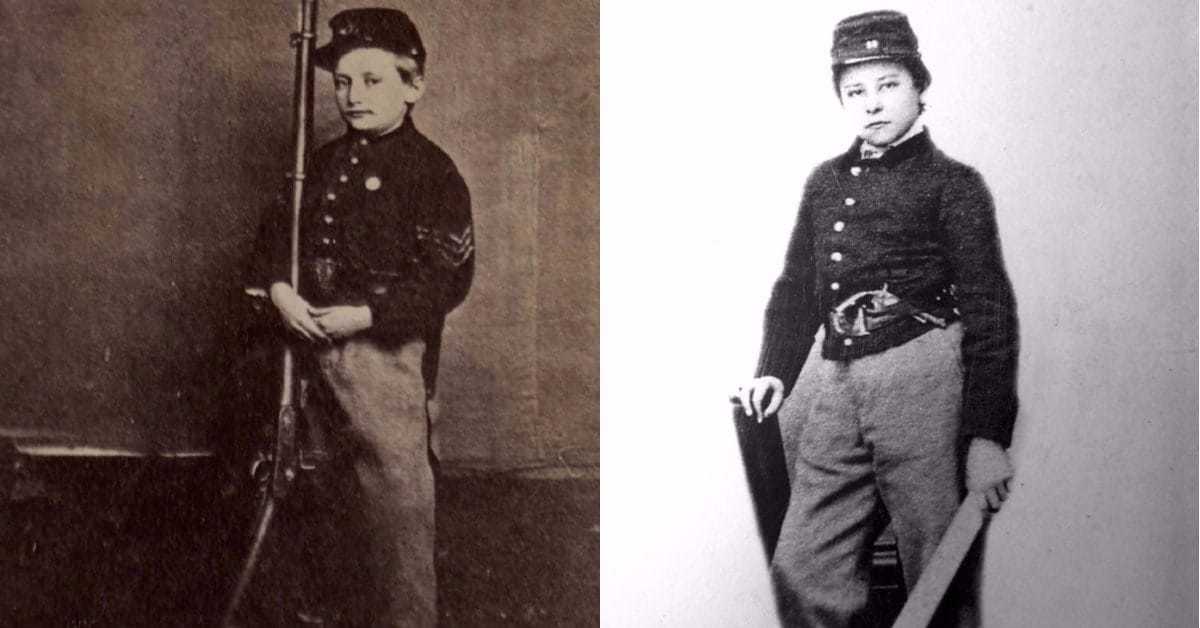

Frank Pettis

Frank Pettis was born in 1850, in Reedsburg, Wisconsin. Aged 11, he joined the Union Army’s 19th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment as a drummer boy in 1862, enlisting in the regimental band alongside his father, a fife player, and serving in a company commanded by his school teacher, captain A.P. Ellinwood.

Drummer boys had been in use for centuries in many armies. The tactics of the era called for closely formed columns and lines to advance and fight in well-ordered formations and in neat rows and lines. As the shouted commands of officers were often difficult to hear above the din and roar of battle, musical instruments, such as bugles and drums, were used to signal commands.

Drummers were utilized to tap out a pace, or rhythm, to assist with the evolutions and formations involved in marching or advancing on opposing forces, and drummer boys, tapping the appropriate beats on their instruments as directed by the officers in charge, accompanied their units into combat and were thus exposed to shot and shell as battle raged and men fell.

Drummer boys were frequently at the side of unit commanders, as they might be needed at any moment to tap out an alert to the unit of pending operations and movements. There were different drum call to signal assembly, notify the officers to gather for a meeting, sound the advance or retreat, or tap out any of the sundry calls that were part of the drummer’s repertoire.

Frank served dutifully with the 19th Wisconsin as it campaigned in Suffolk, Virginia, in New Berne, North Carolina, and in the sieges of Petersburg and Richmond in Virginia. As the war drew to a close, Edward was present as the 19th Wisconsin raced into Richmond, and won the distinction of being the first Union regiment whose colors were triumphantly flown over the captured Confederate capitol building.

After mustering out in August of 1865, young Frank returned home to Wisconsin, where he went to work at his father’s tailor shop, before changing careers at age 20 and becoming a miller. He grew into a prominent member of his community, remained a lifelong active member in the Grand Army of the Republic, the Civil War’s premier veteran’s association, as well as an active member in the Reedsburg Drum Corps.

Frank Pettis raised a family, and died in 1918, aged 68, leaving behind five grown children. His funeral procession was preceded by the Reedsburg Drum Corps, tapping muffled drums, until his coffin was lowered to his final resting place, buried near his former teacher and captain.