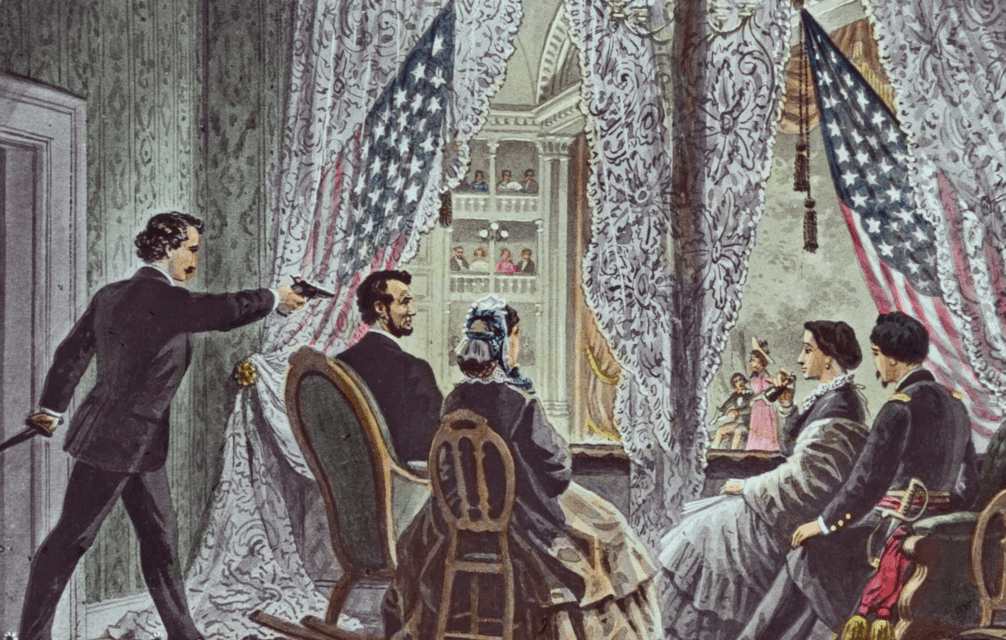

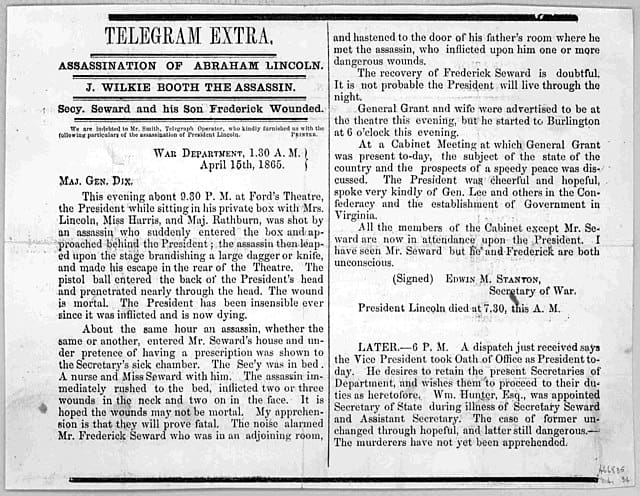

When Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, struck on the evening of April 14, 1865, he left little doubt as to his identity. The murderer leaped from the President’s box to the stage of Ford’s Theater before a full house. He passed an actor well-known to him as he fled toward the back of the theater. Before doing so, he turned dramatically to the audience, brandishing a knife. Some reported he shouted “Sic Semper Tyrannis“, the words of Brutus to the dying Julius Caesar, according to Shakespeare. It was also well-known as the motto of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the late enemy of the Union. Before the dying President was carried out of the theater to the Petersen House across the street, the identity of the assassin was on the lips of onlookers.

John Wilkes Booth was arguably the most famous actor in America, what in a later day became known as a sex symbol. Yet he escaped the scene, and ultimately the city with relative ease. As he fled, an unknown attacker assaulted the bedridden Secretary of State, William Seward, in his home. It was a brutal attack with pistol and knife. Only Seward’s iron brace, supporting his body against injuries sustained in a carriage accident, saved his life. Fear of a coordinated assault on the government took hold. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton took charge, a position he would not relinquish for some time. A nationwide search for John Wilkes Booth and any accomplices began before Lincoln breathed his last early the following morning. No other manhunt in American history to that time compared to what ensued.

1. Washington remained a closed and guarded city at the time of the murder

Although Robert E. Lee had surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia just days earlier, the Civil War had not yet ended. Washington remained an armed camp, albeit a relaxed one. The bridges to Virginia and Maryland remained under guard, with no civilian passage at that hour of the night. Booth shot Lincoln shortly after ten o’clock. He then raced from the theater out the back door, though nobody at the theater reported him limping. His horse awaited him, tended by a stagehand named Joseph Burroughs. Booth mounted and rode off through the streets, leaving turmoil behind. He rode past the Capitol towards the Washington Navy Yard Bridge (modern 11th street). There he encountered his first obstacle in his flight. Passage was not permitted after 9 PM. Booth calmly told the guard he had deliberately waited to pass at that hour, relying on the moonlight to guide him.

Having crossed successfully, Booth waited in the darkness for accomplices David Herold and Lewis Powell. Powell had been given the task of killing Seward, and Herold of guiding Powell to the Seward home, and thence out of Washington via the Navy Yard Bridge. When Herold heard the screams and sounds of violence in the Seward home he abandoned Powell, fleeing prematurely towards Maryland. Powell exited the Seward house bloodied and lost. He fled via alleyways and darkened streets, unsure of where he was going. Herold reached the Navy Yard Bridge sometime after Booth and talked his way past the guard. Though Booth was surprised to see Herold alone, he was reassured by the report of the attack on Seward, and the two continued toward their destination. Unwittingly they had left behind the first breadcrumbs on the trail which would lead federal authorities to them.