The one commonality uniting all of mankind, regardless of time, place, race or sex is that sooner or later, everybody shuffles off the mortal coil, and death comes to us all – although some of us shuffle off that mortal coil in… shall we say, unusual ways. That held true for way back when as much as it holds true today, with the caveat that way back when had some strange deaths that were unique to the circumstances and conditions of their times, and their like will probably never be seen again in our modern era.

That holds particularly true for the Renaissance period, which witnessed some truly weird demises. From Charles the Bad of Navarre, who was burned to death in his bed in 1387 while swaddled in linen steeped in highly flammable spirits, to Hans Steinenger, the burgomaster of Braunau in today’s Austria, who proudly cultivated a luxurious long beard that grew to over four and a half feet in length, only to break his neck tripping on said beard in 1567 while rushing out of a burning house, to James Betts, who suffocated to death after his lover sealed him in a cupboard in Corpus Christi College in 1667 in an attempt to hide him from her father, the Renaissance had its fair share of people who ended their days in highly unusual and strange ways.

Following are 12 of the strangest deaths of the Renaissance:

John of Bohemia

John of Bohemia (1296 – 1346), also known as John the Blind after losing his eyesight ten years before his death, was one of the most celebrated warriors of his era, having campaigned and fought across Europe from the Mediterranean to the Baltic. He was Count of Luxembourg from 1309, and when his father-in-law, the king of Bohemia, died without male heirs, John inherited that realm through his wife and became king of Bohemia from 1310 until his death.

A son of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII, his father made him Count of Luxembourg in 1309, but when his father died in 1313, John was too young to inherit his throne, and so threw his support to Louis the Bavarian, who became Emperor Louis IV in 1314. An early supporter of the Emperor, he fell out with Louis IV after the latter sided with England against France in the Hundred Years War.

During his reign, John fought against Hungary, Austria, England, and the Russians campaigned in the Tyrol and northern Italy and expanded his domain by acquiring Silesia, parts of Lusatia, and most of Lombardy. He lost his eyesight from ophthalmia in 1336 while crusading against the pagan Lithuanians. Any popularity he might have gained at home was offset, however, by heavy taxation to pay for his lavish expenses.

John had strong ties to France, and having been raised and educated in Paris, was virtually French in his outlook and sympathies, even sending his own son to be educated in Paris rather than in his own Bohemian capital of Prague. When king Philip VI of France asked for his help against England’s Edward III, John, despite his blindness, came to the French king’s aid, met him in Paris in August of 1346, and marched off with him in pursuit of the English king.

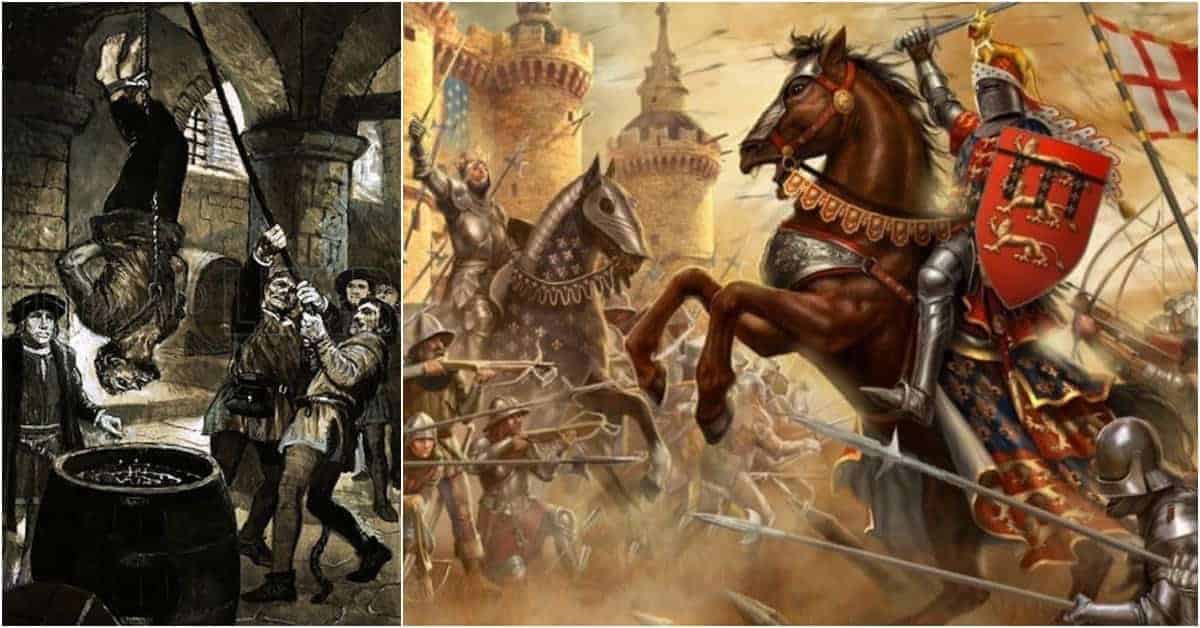

When the armies met at the Battle of Crecy, August 26th, 1346, John was in command of the French vanguard and a significant contingent of the French army. The excitement, sounds, and scent of the battle must have awakened the old war dog in him, for despite his blindness, he ordered his retinue to tie their horses to his and ride into battle so he could deliver at least one stroke of his sword against the English, and thus satisfy his honor by taking an actual part in the battle.

His knights did as commanded, and tied to their horses, the blind king rode into the fight. It did not go well, however. John the Blind, being blind, was unable to judge how far he had gone, and plunged in too deep into the English ranks. He ended up getting cut off and enveloped by the enemy, and in the ensuing melee, the blind king and all of his retinue were slaughtered.