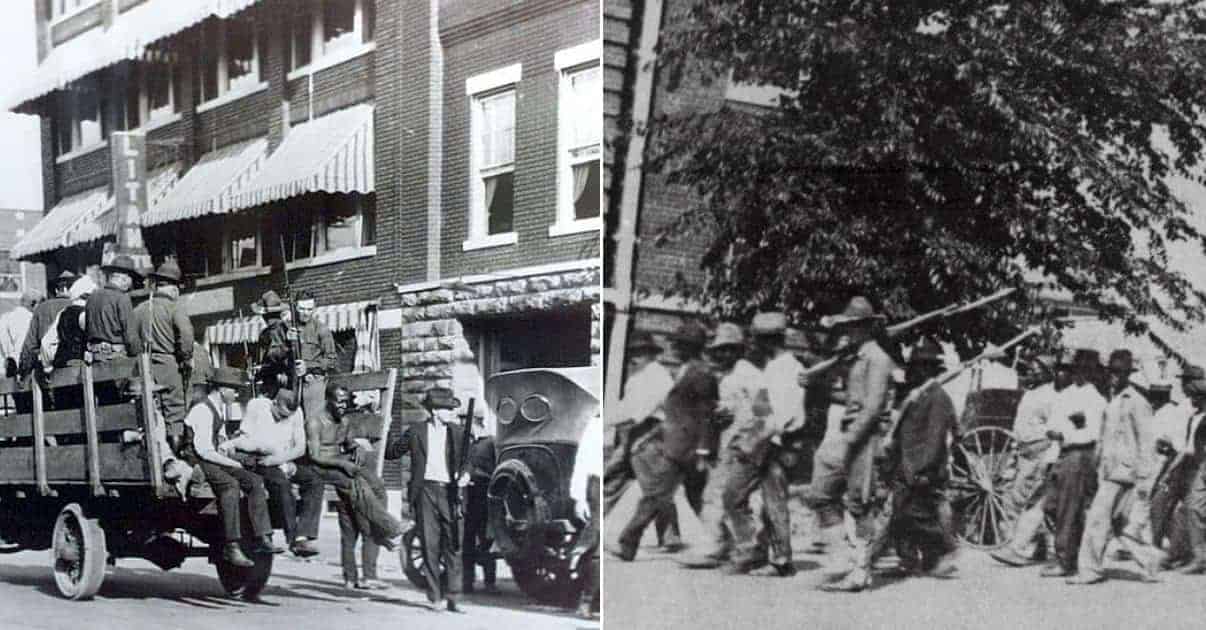

It began with an assumption of sexual assault, which was likely unfounded. The assumption led to a rumored lynching of a young black man. Driven by the yellow journalism of the day it turned into a two-day race riot with still disputed numbers of people killed, more than 800 injured seriously enough to require medical attention, and over 1,200 houses burned to the ground. Ten thousand were left homeless. Not until 75 years had passed was there an official independent investigation into the riot and its aftermath. Another five years passed before the state legislature took action to offer reconciliation to the families of the victims.

Tulsa preceding the riot enforced city-mandated segregation, despite the law calling for it being found unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1917. Lynching was not uncommon in Oklahoma in the two decades before the riot, and the rumor of a lynching about to take place was a major factor in triggering the riot, but not the sole factor. The latent racism which permeated Oklahoma in the 1920s, in law and in life, was the primary factor. The riot was one of the most violent urban events in American history. It is often overlooked by history, other than in Tulsa, and only recently there have there been attempts to understand what occurred.

Here are ten aspects of the Tulsa race riot of 1921 which are mostly forgotten to history.

Tulsa was a segregated city

Oklahoma became a state in 1907. During the ensuing thirteen years, more than two dozen blacks were lynched in the state. Tulsa itself was segregated, and the use of public facilities such as restrooms and drinking fountains was racially restricted. The state constitution restricted black voting. In 1919 black veterans returning from the First World War believed that they had earned the right to vote and riots broke out in several cities across the country. In several northern cities, armed resistance by blacks against attacking whites occurred. Racial tensions were high.

The Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood was a prospering area almost entirely populated by blacks in 1921. Tulsa underwent an oil boom in the early twentieth century, and as the city prospered the Greenwood area flourished. Hotels, banks, grocery stores, haberdasheries, and other forms of commerce were owned by and catered to blacks, offering opportunities and services which were denied them by the white-owned facilities and businesses in Tulsa.

Greenwood featured several large homes occupied by black professionals including doctors, surgeons, dentists and lawyers. There were more than a dozen noted black physicians in the Greenwood area, including Dr. A.C. Jackson, considered to be one of the most capable black surgeons in the United States, according to one of the founders of the Mayo Clinic. There were two newspapers published in Greenwood, both owned by black publishers, which covered local, national, and international news.

Greenwood contained several churches of varying congregations and schools which worked with various youth groups and organizations. The area thrived because employment was strong and the neighborhood provided the black community with the services denied to them by the state and city segregation laws. Still, the interaction between the white and black populations of Tulsa was inevitable as part of daily life, mostly in the area of jobs.

Racial segregation also restricted the personal relationships between whites and blacks. It was considered entirely inappropriate for black men to have any form of a relationship with white women, other than working for them, and even commercial interaction was eyed suspiciously by some whites. An accusation by a white man or woman against a black person nearly always led to a conviction, as blacks were denied the right to sit on juries (only registered voters could be jurors). The fear of white lynch mobs was also present, in Tulsa as well as in the rest of the state. Racial tensions were high, both from the news of riots during the summer of 1919 (known as the Red Summer) and from the competition for jobs after the First World War.