Masks have been part of the ritual of death for millennia. Some, such as those of Egyptian pharaohs, were idealized representations of the deceased, designed for the tomb. Others, such as the death masks of ancient Rome, preserved the exact face at the moment of death. These masks were for the living, forming the imagines maiorum, of the deceased that joined the ranks of the family’s ancestors. This type of death mask continued into the middle ages and beyond, with casts of faces being used to preserve and replicate the faces of the dead as post-mortem works of art.

Throughout time, the method of creating death masks remained the same. The face of the corpse would be lubricated or protected in gauze before clay or wax was applied to make an imprint of the deceased’s features. However, the motivation behind the masks morphed with time. People began to create death masks for curiosity as well as commemoration. They became the subjects of science and study as well as art. Some were made to send a message- or purely for profit, Many survive today and give us an insight into the actual faces of some of the most famous and infamous characters in history. Here are just 10.

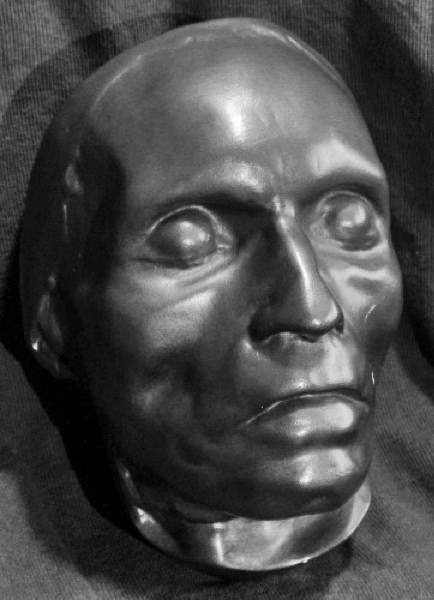

Beethoven

Death masks have been made for a number of composers -Haydn, Chopin, Mozart, and Liszt amongst them. However, none shows the ravages of time more so than the death mask of Ludwig Van Beethoven. In his early thirties, the composer began to lose his hearing. Despite this, Beethoven persevered with his music and by his fifties was at the height of his success. However, a decline in his health marred the last years of his life, and by the end of 1826, Beethoven suffered from a severe bout of sickness and diarrhea.

It was an illness from which he did not recover. By the following March, it was clear that Beethoven was dying. His friends gathered about his bedside in Vienna and waited for the inevitable to happen. On March 24, 1827, a Catholic priest gave Beethoven the last rites, and on March 26th, he finally passed away. Now, however, thoughts of the composer’s earthly, rather than his spiritual immortality were very much on his friend’s minds.

The day after Beethoven’s death, his friend Stephen Von Beuning wrote to the composer’s secretary and biographer Anton Schindler: “Tomorrow morning a certain Danhauser wishes to take a plaster cast of the body. He says it will take five minutes, or at the most eight. Write and tell me whether I should agree. Such casts are often permitted in the case of famous men, and not to permit it might later be regarded as an insult to the public.”

Beethoven’s friends must have agreed because, on March 28th, Josef Danhauser, a Viennese artist had made a cast of Beethoven’s face. This mask preserved for posterity the ravages of the composer’s last disease upon his body, contrasting starkly with a life mask made of Beethoven in 1812. “The master’s appearance had changed greatly,” wrote Ernst Benkard, author of ‘Undying Faces: A Collection of Death Masks.” The dead, 57-year-old Beethoven’s face was now skeletal with sunken cheeks as opposed to the full vibrant, impatient features the composer had in his early forties.

So what caused this change? An autopsy of Beethoven has shown that the composer was suffering from cirrhosis of the liver due to alcohol abuse of hepatitis. The modern reanalysis, however, shows Beethoven was also suffering from lead poisoning caused by illegally fortified wine. Scientists detected this poisoning from elevated levels of lead in hair taken from the composer by his friends as mementos after his death. Beethoven’s death mask, however, is not the only one to preserve the ravages of its subject’s passing.