Suppose one had a dispute with one’s neighbor over encroachment on one’s property. In the modern world, one would attempt to resolve said dispute through negotiation, or arbitration, or litigation. Legal fees would ensue, and the case could molder in court dockets for months, or even years, frustrating the parties involved. In the Middle Ages, such niceties of the law did not necessarily apply. Beginning in the Germanic lands, other means of resolving legal disputes evolved. They were based on the belief in divine intervention in the secular affairs of man, that God would not allow evil to prevail over truth. Judicially sanctioned trials could and were used to resolve all sorts of legal issues, including guilt and innocence for those accused of crimes. Two of the most common were trial by ordeal and trial by combat.

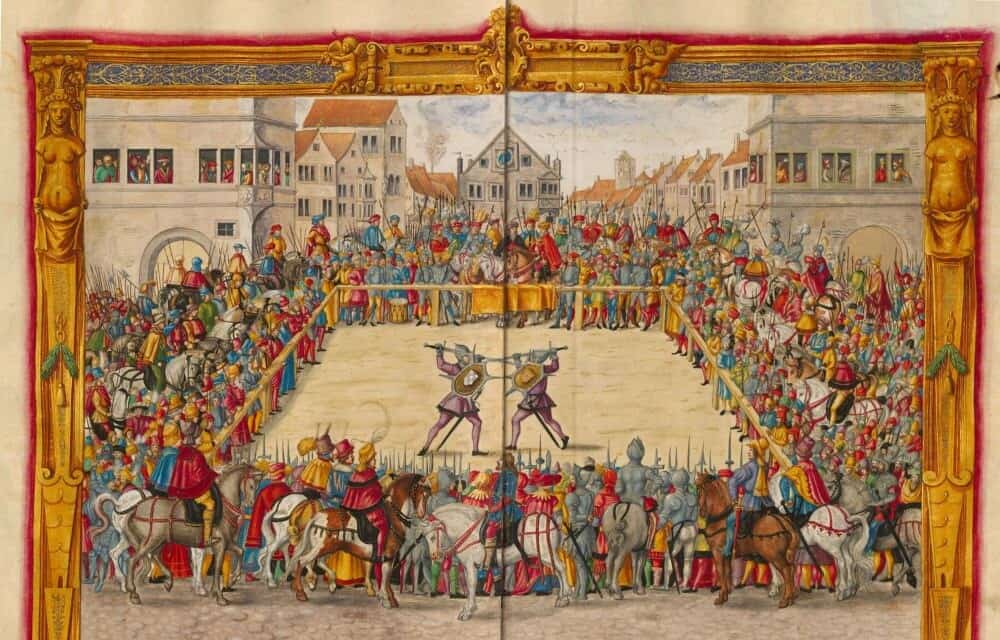

Both could be ordered by a magistrate, and in the case of the latter could be requested by either party as a legal right. Though neither was ever fully sanctioned by the ultimate legal authority of the time, the Pope, nor were they ever banned, at least not in practice. Trial by ordeal involved establishing one’s innocence of a crime through surviving torture, while trial by combat, also called judicial combat, established one’s innocence by vanquishing an open in man-to-man battle. One did not necessarily need to kill one’s opponent to prevail, though the loser of judicial combat usually faced execution anyway, for having perjured himself before the court and God. The combats were brutal, using the weapons of the medieval period, the broadsword, battle axe, mace, chains, daggers, and among knights, squires and the nobility, the lance. Here is the bizarre story of the right of judicial combat.

1. European law was a quagmire of conflicting statutes during the Medieval period

Officially, the prevailing law in Europe of the Middle Ages was Roman Law, which is the law of the Roman Catholic Church. Unofficially, throughout the tribal lands of central and western Europe, ancient customs and common law remained in effect. Roman authority was often too distant to be enforced, even if local rulers were inclined to do so. Most were not. Legal codes of the Germanic tribes dating to the 8th century spelled out the process for judicial combat, including when it could be applied, the conditions of the actual combat (which varied depending on the nature of the dispute), and the punishment for a survivor, should one emerge, defeated and thus obviously guilty. Gradually, the idea of judicial combat took on some of the features of the much later Code Duello, in which the accusing party awaited the accused at an appointed time and place.

The weapons to be used were selected and agreed upon, clothing to be worn prescribed by law, and the conditions of victory or defeat preordained. A combat need not necessarily be to the death, though the possibility of that eventuality was recognized by all involved. Killing or defeating one’s adversary established the victor as the truthful party, meaning a surviving combatant still faced legal penalties for whatever transgression led to the combat in the first place. In some instances, magistrates did not agree that judicial combat was warranted and instead ordered trial by ordeal for the accused party as a means of establishing guilt or innocence. Trial by ordeal, which dated to more than 17 centuries before the Common Era, assumed that during an ordeal a merciful God would intercede through a miracle if a supplicant was innocent.