During the American Civil War slaves and free blacks served the Confederate Army, in many roles and duties. They accompanied the Army of Northern Virginia in its two invasions of the North, in the Antietam Campaign of 1862, and the Gettysburg Campaign of the following year. The Antietam Campaign took place in Maryland, a slave state at the time. The later invasion of Pennsylvania which culminated in the Battle of Gettysburg marked the only time large numbers of slaves were carried into a free state during the war.

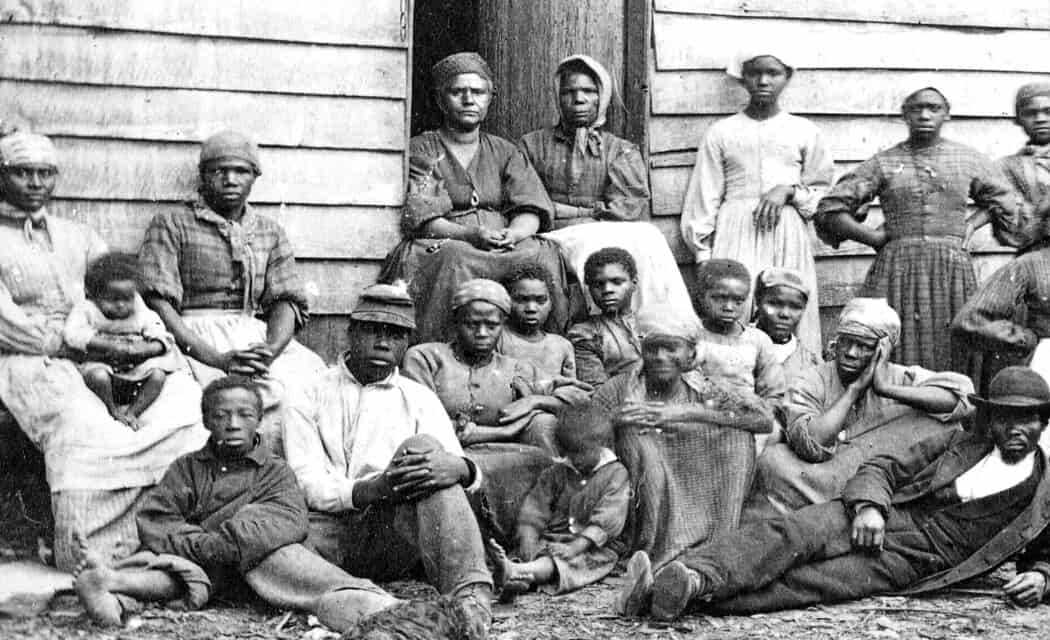

Newspapers and magazines in the South touted the “loyalty” of slaves towards their masters, supported with letters from soldiers serving in the southern armies. One Confederate soldier wrote of the slaves during the Gettysburg Campaign, “…they preferred life and slavery in Dixie to liberty at the north”. Their role in the army did not include combat service, though many came under fire. They built fortifications, dug trenches, drainage ditches, canals and latrines. They erected tents and huts, served as teamsters, tended to livestock, cooked, did laundry, and cut and hauled firewood. Here is the largely unknown role of slaves in the service of the Confederacy during the American Civil War.

1. The South had a slave economy before and during the war

Long before the guns at Fort Sumter heralded a war between the states, necessitating raising of large armies in the South, slave labor drove the economy. Slaveholders frequently hired their slaves out, to gristmills, cotton gins, shipping companies, and the South’s relatively few factories. Slave labor worked the tobacco processing factories and the iron works, including Richmond’s Tredegar Iron Works, which over the course of the war produced nearly half of the artillery used by the Confederate Army. Factories and other businesses paid for the slave labor, but the wages went to their owners. In some cases, workers kept a small percentage of their pay as an allowance for food and clothing.

At the onset of the war, slaves were “hired” in such a manner to erect coastal fortifications and key defensive positions on internal rivers. Forts Henry and Donelson, the sites of early Union victories, were erected by Confederate engineers using slave labor. Slaves built the defensive bastion at Vicksburg, as well as those of Island No. 10 in the Mississippi. As the South geared up for war, with states first exhorting and soon drafting white men into the army, slave labor built railroads, carried supplies on wagons to depots, and traveled to the assembling military encampments. They did not organize into military units such as companies and regiments, but were assigned to military units as laborers.