There are those who still believe that America’s bloody and tragic Civil War was not about slavery nor white supremacy. Followers of what came to be known as the “Lost Cause” contend that the Confederacy was a heroic stand against the tyranny of a federal government intent upon trampling the rights of the individual states and their citizens. Such belief is denial of historical truth. In its statement of the causes of secession, the State of Texas, for example, wrote, “We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable”.

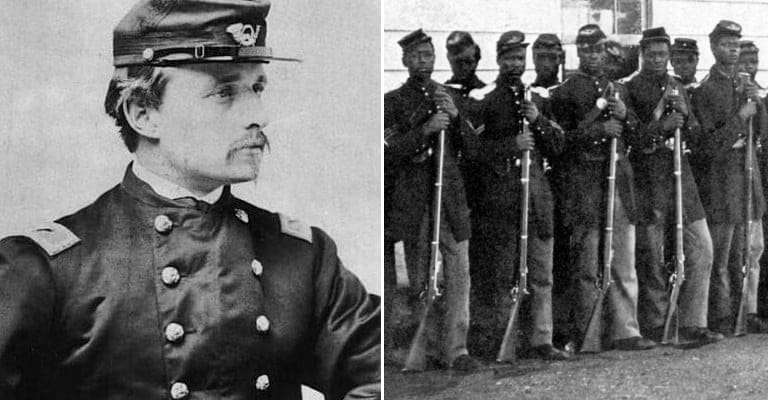

It was a belief by no means limited to the South, even some northern abolitionists considered the white race superior to all others, though all were equal when considered in the eyes of the law. Such beliefs made the raising of black regiments of troops, called “colored” at the time, highly controversial. The Union army created several such regiments, officered by whites, following the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. One of the most famous was the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Here is its story, and that of its commander, Robert Gould Shaw.

1. Robert Gould Shaw came from a prominent abolitionist family in Boston

Robert Gould Shaw was the son of a Boston family which was strongly abolitionist, and well-placed within the community and the Unitarian Church. He was the only son, with four sisters, and the wealthy family relocated to Staten Island when he was ten. He studied for a time at what later became Fordham Preparatory School, and the Jesuit influence and that of an uncle led him to convert to Catholicism. He then traveled and studied extensively in Europe, and it was there when he first became acquainted with Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The book significantly affected his thinking regarding slavery in America.

Shaw returned to the United States in 1856, toyed with the idea of entering West Point, but instead enrolled at Harvard University. He did not complete his degree, leaving school in 1859, one year before his class was to graduate. Restless and bored, he returned to Staten Island, where he worked as a clerk in an uncle’s mercantile company. It was a position he found as boring and dull as school. By 1861, when Abraham Lincoln called for volunteers to put down the insurrection in the South, Shaw was longing for adventure and a change of scenery. He joined the 7th New York Militia for the 90-day period established by Lincoln. The unit saw no action, and after three months it dissolved.