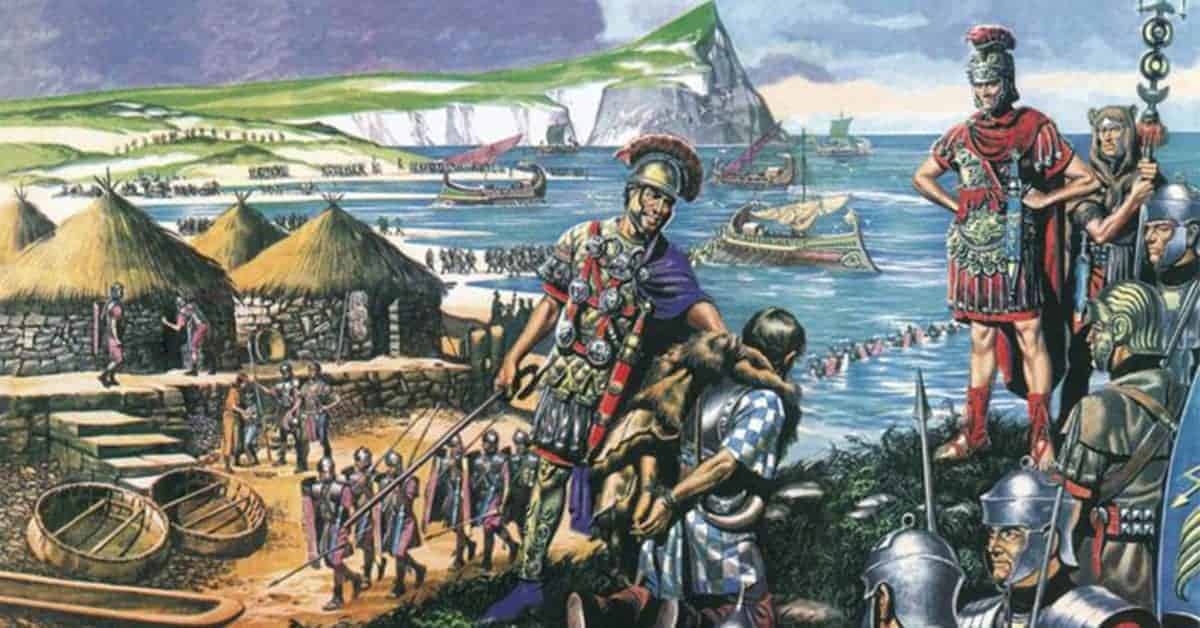

The Romans first turned their attention to Britain in 55 BC when Julius Caesar launched raids in the South-East of the country. While this first incursion was relatively unsuccessful, his second attempt, in 54 BC, led to the installation of King Mandubracius, a monarch friendly to Rome. However, Caesar did not keep any territory for Rome; instead, he ensured it was restored to the Trinovantes. The Romans did not return until 43 AD, but on that occasion, they conquered a significant amount of territory and held it for over 350 years.

A War of Prestige

When Augustus was emperor, he decided that the age of conquest had to end because the empire was already overextended. Matters were not helped by the disaster at Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD. However, Emperor Claudius decided that an invasion of Britain was in order in 43 AD. The main reason was prestige. Rome did not need new territory, and its economy was booming so there were no territorial or financial motives behind the invasion.

Upon the death of Caligula in 41 AD, Claudius found himself on the throne and immediately faced opposition from the Senate. He believed that a quick military victory in Britain would lend legitimacy to his reign. He sent an enormous 40,000 man army to Britain under the command of Aulus Plautius. The Romans soon won a crushing victory over the Catuvellauni near the River Medway and took the city of modern-day Colchester, the enemy’s HQ. Claudius was present for this part of the conquest and appointed Plautius as the first Roman Governor of Britain.

Crushing the Iceni

If the Romans thought it would be a quick and easy conquest, they were sorely mistaken as they faced almost constant resistance wherever they went. One of the fiercest groups of rebels was the Iceni Tribe led by Queen Boudicca. In 60/61 AD, the Governor of Britain, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, had his army in Anglesey when the Iceni tribe rose against the Romans.

Other tribes, including the Trinovantes, supported the Iceni and together, they destroyed Colchester. Paulinus quickly marched to Londinium (London) because he knew it was the next target. However, he realized that the Romans didn’t have the numbers to defend the city, so they fled. Boudicca led 100,000 troops to the city and burned it; then she moved on to St. Albans and did the same. Overall, Boudicca’s army killed up to 80,000 Romans.

Paulinus was eventually able to regroup, and he won a stunning victory over the rebels at the Battle of Watling Street. Ancient historians claim that a Roman army of 10,000 defeated a rebel army of 230,000. While the rebel number is likely inflated, Paulinus was heavily outnumbered but inflicted major losses on his enemy. This victory helped Rome gain control of Britain and probably saved the territory as Nero was considering withdrawing all troops from the colony before the victory at Watling Street.

Boudicca either died of illness or committed suicide, and the revolt was at an end. A lesser-known revolt in 69 AD was also crushed as the Romans slowly gained control. Under the leadership of Governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the Romans conquered the north of Britain as far as Moray Firth in 84 AD with victory at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Agricola was recalled to Rome soon after, and from then onward, Roman occupation in Britain took on a more defensive posture.