For the Romans, the way you shuffled off your mortal coil was just as important as the way you bore it through life. Just as you could live a virtuous existence, so too could you die a virtuous death. This didn’t just mean dying gloriously in battle (although the Romans were pretty into that as well). Before Christian moralizers preached suicide as sin, taking your own life could also count as a noble way to go. And although the most famous example from the ancient world might come from Greece, not Rome, with the death of Socrates, the Romans did their fair share of imitation.

There were, of course, also fundamentally bad deaths. Being murdered or committing suicide on the run was particularly shameful, as was being slowly and unknowingly poisoned by someone in your own immediate family—particularly by a wife. Worst of all was a death that plunged the family (or worse still the Empire) into chaos or civil war. It shouldn’t surprise us that many of the aforementioned examples are taken right from the wacky lives of the Twelve Caesars.

The lives (and deaths) of the first twelve emperors are remarkably well-documented by the court biographer Suetonius. If you haven’t read him, and you’re interested in early Roman emperors, you really must. More than just being about the juicy details, Suetonius’s biographies tell us something about the nature of imperial power. And the way in which his subjects meet their end always reflects something of the way they lived their lives.

Julius Caesar

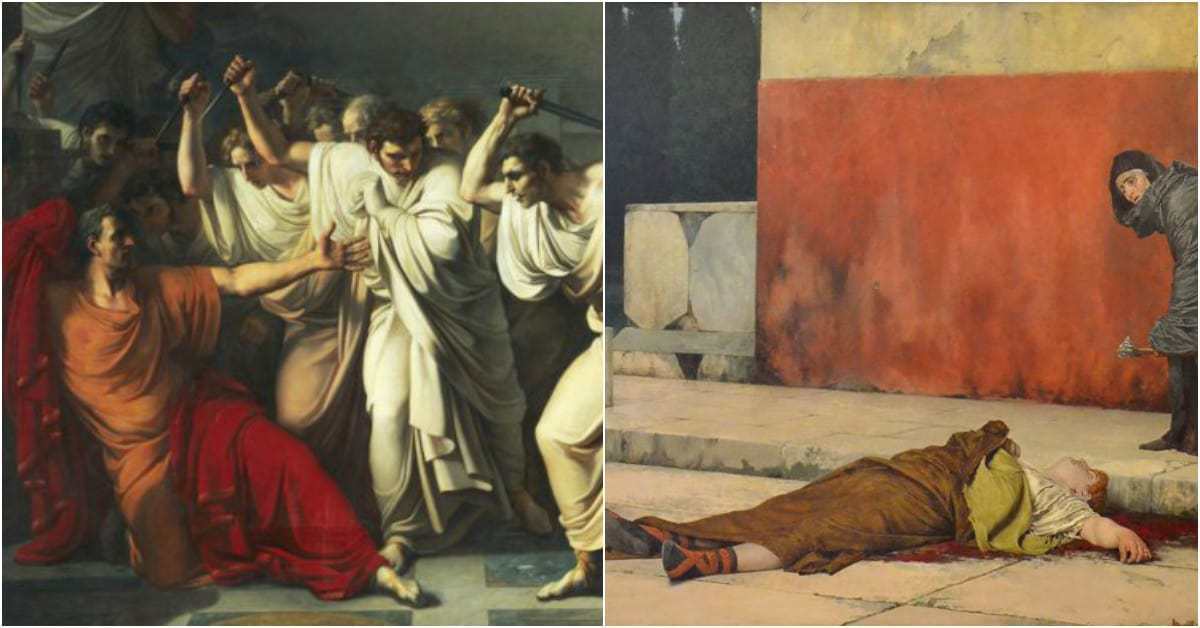

If there’s one date from Roman history people save to mind, it’s March 15 44 BC. Better known as the Ides of March, on this day the self-declared dictator in perpetuity Julius Caesar was murdered, set upon by a group of senatorial conspirators in the newly constructed senate house, and stabbed 23 times in the name of preserving the Republic.

Chief among the conspiracy’s leaders were Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Brutus’s role was particularly apt. His great ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, had been responsible for driving out the last of Rome’s kings, Tarquinius Superbus, after the rape of Lucretia. He had then gone on to found the Roman Republic, serving as one of its first consuls in 509 BC. Now his memory was being called upon to offer courage to his ancestor in the face of a new tyrant.

Caesar was assassinated shortly after entering the new senate house, recently annexed to the enormous Theatre of Pompey—the first permanent stone theatre in Rome’s history. We’re told that a senator approached him, petitioning for his brother’s recall from exile. After being brushed away, the senator made a grab for his toga. Caesar rebuked him, accusing him of violence, at which point another senator lunged at Caesar’s neck with his dagger.

The dictator caught the dagger in his hand, but it only delayed the inevitable. Within seconds, dozens of senators were hacking away at the dictator with daggers produced from under their togas. The most famous part of Caesar’s death is the dying dictator looking upon his former friend and uttering the immortal words, Et tu Brute? This phrase is, however, Elizabethan in origin, immortalized by William Shakespeare in his eponymous play Julius Caesar.

According to ancient sources, Caesar either said nothing or, as some suggested, uttered the Greek phrase καὶ σὺ τἐκνον which sounds a bit like “kai say teknon” and means “you too, young man?”Although most aristocratic Romans were bilingual, it’s hard to believe that a man who’d been stabbed two dozen times out of nowhere would have produced a Greek quip as he lay bleeding to death.

“καὶ σὺ τἐκνον” — “You too, young man?”

Though we might prefer this dramatic version, it’s more likely that the other versions are more accurate. Sad though it may be, in all likelihood the dying dictator pulled his tunic up over is face to preserve what dignity remained before being left to bleed to death beneath the statue of his former rival, Pompey Magnus.