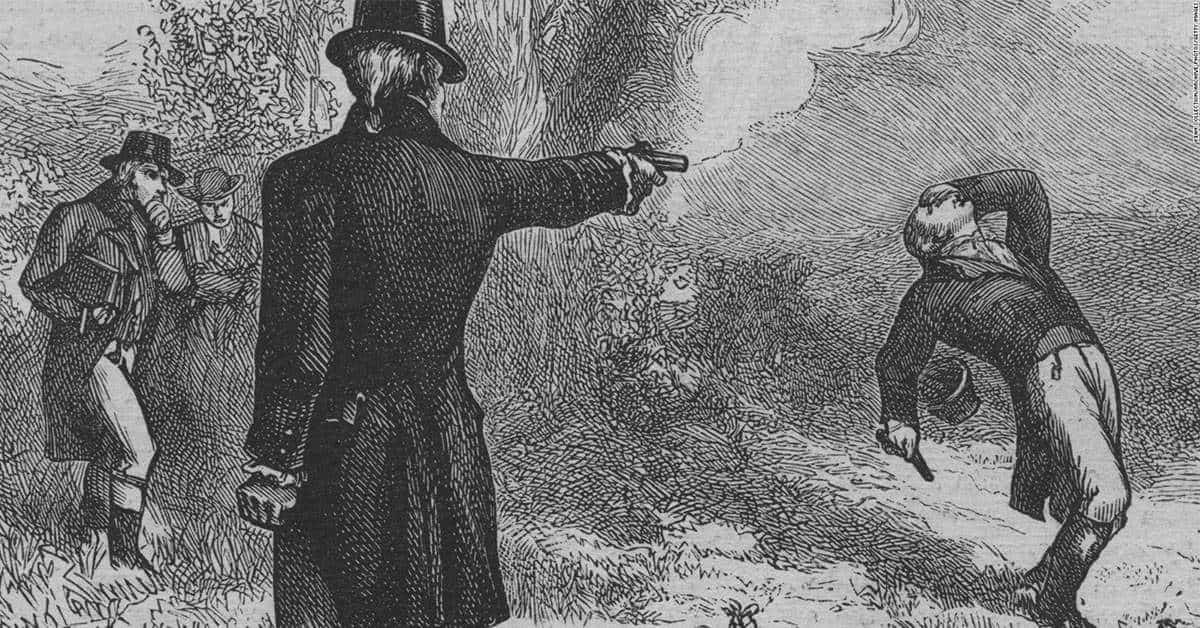

On the hot morning of July 11, 1804, the former first Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, Alexander Hamilton, stood on a narrow strip of land in Weehawken, New Jersey. Although the practice of dueling – also known as an Affair of Honor – was illegal in New Jersey, the ground upon which he stood was known in both New Jersey and across the Hudson River in New York City as the Dueling Grounds. Hamilton was familiar with the grounds and the practice of dueling, having been engaged in at least eleven such affairs before that day.

In fact, he had, according to his own letters, twice stood before the opponent he faced that day, the sitting Vice-President of the United States, Aaron Burr. (Burr later claimed that they had faced each other but once before; official records are non-existent because dueling was a crime).

While waiting for Burr, Hamilton’s thoughts in the moments before the duel commenced may have strayed to an earlier day when on the same ground his eldest son had stood facing an offended gentleman in yet another Affair of Honor. Indeed, Philip Hamilton had used the same set of pistols, borrowed from an uncle, which Hamilton and Burr were using in their confrontation; there is a fifty-fifty chance the father held the same weapon his son had held on that same ground when he, the younger Hamilton, had received his fatal wound.

That Alexander Hamilton died at the hand of Aaron Burr in an ill-advised duel is a well-known event in American history. That Hamilton’s eldest son died from wounds received on the same ground, using the same weapons, just a few short years before is one of America’s lesser-known tragedies.

Philip Schuyler Hamilton was the firstborn son of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton and her husband Alexander. Born in 1782, in the penultimate year of the Revolutionary War, Philip was the apple of his father’s eye. He had what was considered at the time a liberal education, eventually graduating from Columbia College in New York (today’s Columbia University) with honors in 1800. He studied law by the then-common method of reading it under the tutelage of a practicing attorney.

As the son of a prominent and well-to-do citizen of New York – already well on the way to being the nation’s financial capital as well as its center of entertainment – Philip enjoyed the city’s diversions in the company of many friends. He was, somewhat in the mold of his accomplished father, possessed of a sense of fun which in today’s world would label him a “player.” His father gently attempted to reign him in with a daily schedule suggesting an itinerary which included time set aside for recreation, but there is little evidence that the son followed the father’s plan.

By 1800 the American political scene had developed into a system of political parties, despite the grave warnings to avoid partisan politics from the beloved George Washington. The political parties had emerged in large part out of the debates over the constitution described in The Federalist Papers, in which Alexander Hamilton had argued for a strong federal government, in opposition to the Democratic-Republicans, who believed that true power resided in the several states.

By 1800 the young American republic had also nearly gone to war with revolutionary France, an event which led President John Adams to call for the formation of an American Army, with Alexander Hamilton – a former military aide to Washington – at its head as commander. War with France was averted by cooler heads on both sides despite several naval clashes, but passionate discourse on the subject remained rife in the United States.