In the year 1830, at the height of the transatlantic slave trade, there were an estimated two million people enslaved in the United States. In the vast majority of cases, they were Africans or the enslaved descendants of Africans, forced to work on plantations owned by wealthy, white individuals. But this wasn’t always the case. The history books also show that some slaves were owned by people of color. More specifically, according to the historian Carter G. Woodson, in 1830, 3,775 freed former slaves owned 12,100 slaves between them, a tiny fraction of America’s enslaved millions.

In many cases – and, perhaps in the majority of cases – people of color with slaves only owned one or two individuals. And even this was for personal, rather than business reasons. Upon earning their own freedom, they would purchase enslaved relatives in order to be close to their loved ones. But in some cases, freed slaves were every bit as business-minded, entrepreneurial and even ruthless as white plantation owners. Indeed, a handful of people of color not only managed to buy their own freedom, but they went on to amass small fortunes. Sometimes this money was made through the sugar or cotton trades, often on the back of slaves of their own. And, while some treated their slaves kindly, others were far more ruthless.

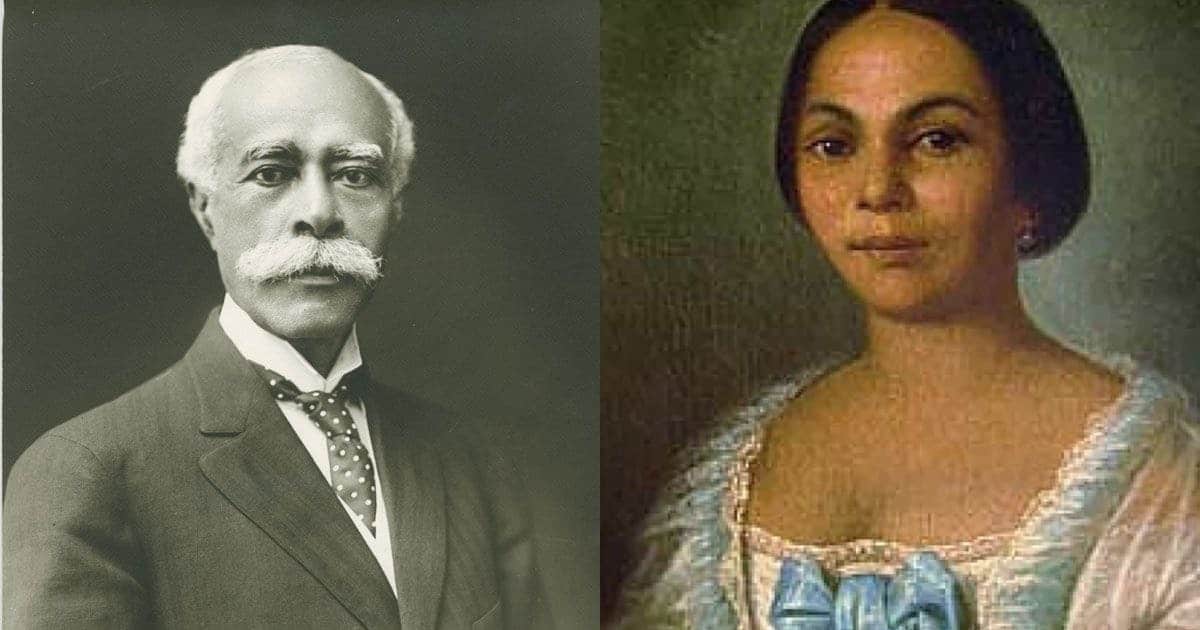

Anthony Johnson

When the first British colonizers settled in Virginia, they faced a problem. How could they get people to work the land then, and in the decades to come? They came up with the concept of ‘indentured servitude‘. Under this system, anyone wishing to travel to America but lacking the money could have their passage paid for them by a benefactor. In return, they would give their labor for a fixed number of years. Once they had fulfilled their obligation, they would be freed from their service and, so the theory went, they would have gained some valuable skills and be ready to start making a life for themselves in the new world. In many cases, people didn’t live long enough to fulfill their contracts and earn their freedom. But some did, including a certain Anthony Johnson.

Johnson came to the United States in traumatic circumstances. Captured by an enemy tribe in his native Angola, he was sold to an Arab slave trader and sent to Virginia aboard a ship called the James. He landed in 1621. Immediately upon his arrival into the British colony, Johnson was sold to a white tobacco farmer. As was the system, he was required to work to gain his freedom, though the precise number of years he was indentured for was not recorded. In 1623, a year after Anthony (or ‘Antonio’ as he was still known as then) almost lost his life in a skirmish with the Powhatan tribe, a female by the name of ‘Mary’ arrived to work at the plantation. She fell for Antonio and they married. Their union would last for more than four decades.

At some point, believed to be 1635 or 1636, Antonio gained his freedom. Upon release of his contract, he changed his name to Anthony Johnson and started working on a plot of land he had acquired through his terms of freedom. By 1651, he had acquired a further 100 hectares of land. To work his holding, he bought the contracts of five indentured servants, including his own son, Richard Johnson. One of the other indentured workers he held the contract for was a man named John Casor, who would earn a place in the history books himself. By 1643, Casor had earned his freedom under the traditional system. Johnson agreed to work for another farmer, but Johnson refused to let him go. He sued the other plantation owner and, in 1655, he won in court. Casor was returned to Johnson and would be indentured to him indefinitely. According to historians of the time, this was the first time a black person in America was made a slave, and a slave for life, with a black plantation owner as his master.

In 1661, Virginia had passed a law permitting any free man to own slaves as well as indentured servants. Johnson himself died in 1670. By that point, he was living with his family on a 300-acre plot of land in Maryland. Mary outlived him for just two years. However, she did not gain possession of his farm. Neither did either of his two sons. Instead, the land was given to a white man, with the judge presiding over the inheritance case ruling that the color of his skin meant Johnson was not technically a citizen of the colony’.