Most people today grew up and live in societies in which concepts such as egalitarianism and equal treatment before the law are established tenets of governance and social organization that are, even when not actually practiced, at least widely preached as a hoped for ideal and aspiration. Throughout most of recorded history, however, the majority of mankind lived in highly stratified societies with stark class divides, in which a relatively small aristocratic elite lorded it over a mass of oppressed, exploited, and cowed commoners.

Most said commoners were peasants, tied to the land and toiling in conditions of de facto peonage and serfdom for the betterment of their social betters, who seldom bothered to conceal their contempt for the peasants, whose very occupation’s name was often used as a pejorative. Social custom and religion, with its promise of a better life in a world to come, did much to reconcile the peasants to their lowly lot in this world. If that failed, the nobility’s monopoly of government and access to organized and disciplined military force often sufficed to cow the peasantry and keep it in line.

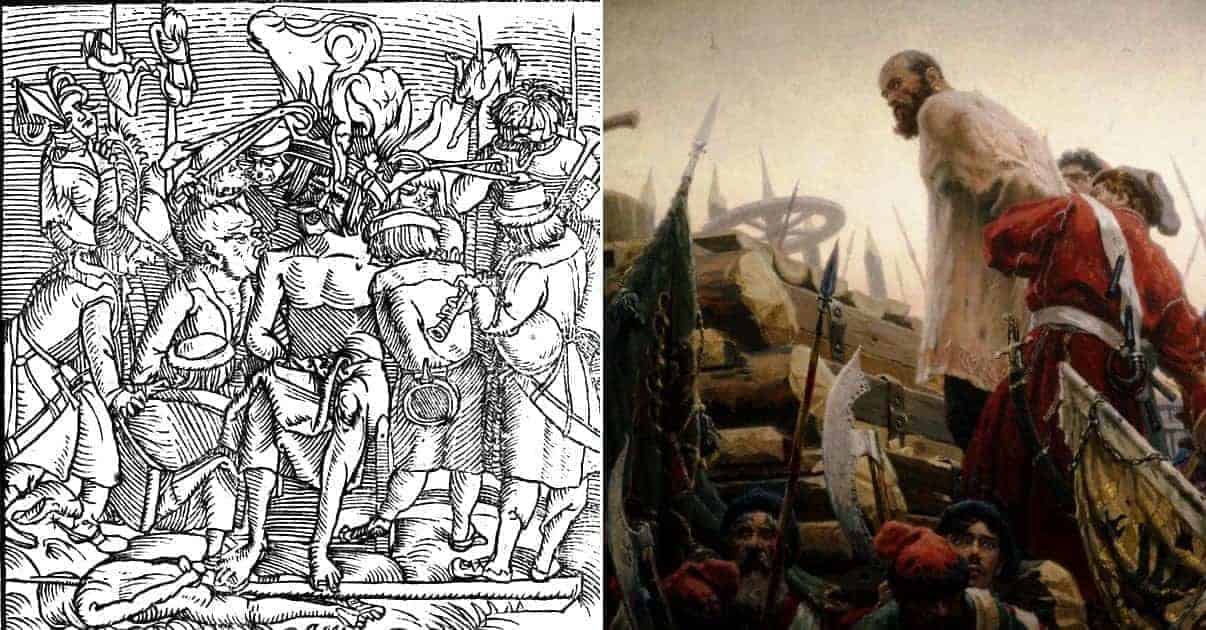

However, sometimes conditions got so bad, and the oppression and injustice grew so unbearable, that the peasants snapped, and notwithstanding the poor odds of success and the high risk of massive and vicious retaliation at the end of the road, took to arms and rose up in revolt. Throughout history, most such uprisings ended in failure and widespread massacre, as the forces of the landlords and nobility exacted bloody vengeance on the despised peasants who dared challenge the natural order. Nonetheless, such rebellions continued to erupt whenever the agrarian class could take it no more.

Following are twelve of history’s greatest peasant revolts.

Red Eyebrows Uprising

Between 2 and 11 AD, the Yellow River in China underwent disastrous course changes that led to floods and famines and widespread dislocation and hardship. Amidst the turmoil, civil war erupted in 8 AD when Wang Mang, a government official, overthrew the Early Han Dynasty which had reigned over China for two centuries, and founded the short-lived Xin Dynasty in its stead.

The political turmoil, natural disasters, hardships and hunger, took place against a backdrop of resentful peasantry, whose main grievance was a rise in debt slavery and a steady consolidation of agricultural land into large tracts controlled by powerful magnates. The former independent yeoman peasant owners of those plots were reduced to tenant farmers or serfs, tilling what had once been their own holdings on behalf of others, or were kicked off the land altogether and reduced to a life of itinerant wanderers.

In response to the turmoil and dangers, and to protect the interests of the peasants, a secret society, whose leader spoke through mediums, organized bands of armed Chinese peasants known as the Red Eyebrows. They took their name from the color of the eyebrows of their members, who painted their faces to look like demons, and in 15 AD, they initiated their first acts of armed resistance. The Red Eyebrows’ popularity steadily grew, and by 17 AD, their armed defiance had become a widespread peasant revolt that came to be led a Fan Chong.

In the imperial palace, Wang Man proved politically incompetent, and in 19 AD, he responded to the peasant revolts of the Red Eyebrows and others by raising taxes. That only fueled and supercharged the various rebellions, which soon consolidated into a massive insurrection as the disparate rebel bands united under the banner of the Red Eyebrows and the leadership of Fan Chong.

In 23 AD, the Red Eyebrows played a key role in the defeat and overthrow of Wang Man and the extirpation of his Xin Dynasty. That allowed an opening for Liu Xuan, a member of the Han royal family, to reestablish the Han Dynasty and declare himself emperor. His rule did not sit well with the Red Eyebrows, however, so they overthrew him, and placed a child Han descendant on the throne as a puppet emperor, while they ruled China in his name.

However, while militarily brilliant, the Red Eyebrows proved incompetent at governance, and their misrule soon led to widespread revolts. Their puppet emperor was overthrown and replaced by another Han descendant, Liu Xiu, who forced the surrender of the Red Eyebrows and brought their movement to an end, then went on to found the Later Han Dynasty, which reigned for two centuries.