“Wisely they leave graves open for the dead

‘Cos some to early are brought to bed.”

The medical technologies of today provide invaluable services. We have access to effective medicines, proper diagnoses, successful surgeries, and longer lifespans. Doctors are also capable of something many may take for granted in this day and age: definitive proof a person is deceased. It may seem as if declaring one dead should be a straightforward process, however, physicians and morticians alike in the 18th and 19th centuries were practicing with less certainty than their modern counterparts. Reliance on rudimentary methods of observation such as smell and touch were the gold standard.

Following the success of Mary Shelley’s 1818 Gothic novel, “Frankenstein“, loved ones of the recently deceased found themselves questioning what distinguished life from death. “Taphophobia”, the fear of being buried alive, disseminated quickly and mistaken death preceding a live burial was to be avoided at all cost. The pandemic of doubt spread across Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States, sparking a century’s worth of both grotesque and ingenious devices to ease the living’s mind of any doubt associated with live burials.

“Frankenstein” was not the only story of reanimation to be spawned out of the live burial craze of the Victorian Era. Generations of stories passed down from families and communities only served to flame the fires of fear associated with being buried alive.

One particular story coming from the Mount Edgcumbe family tells the tale of Countess Emma. Emma married the wealthy Earl of Mount Edgcumbe in 1761. When Emma was pronounced dead, she was buried with a valuable ring. A sexton who had spied on the family while the burial was taking place, noticed the ring and returned under the cover of darkness to retrieve it. When the sexton went to snatch the ring, Emma awoke, confused and clothed in her burial shroud. The sexton, who was understandably frightened at the corpse’s reawakening, ran away never to be seen again. The Countess made the half-mile journey back to the Edgcumbe Estate, shocking everyone who had thought she was dead. To this day, the estate has ‘Countess’s Path‘, a walkway commemorating Emma’s journey from the grave back to her home. Countess Emma of Edgcumbe finally met real death in 1807.

Most of the stories have questionable accuracy. Nevertheless, the instinctual trepidation of death allowed these stories and culture of morbid scientific inquisition to flourish.

These are the interesting and gruesome death tests throughout Victorian history…

Safety Coffins

Cholera outbreaks, bacterial infections causing severe diarrhea and dehydration, were prevalent in the 18th and 19th centuries. They left not only the communities it impacted very ill, but also very fearful of being buried alive. It was during this time clever feats of engineering sought to comfort the panicked population. One such invention was the safety coffin. The safety coffin provided its occupants the ability to escape from their newly found entrapment and alert others above ground that they were indeed still alive. Many safety coffins included comfortable cotton padding, feeding tubes, intricate systems of cords attached to bells, and escape hatches. Unfortunately, most neglected methods for providing air.

An account from 1791 explains the death of a man from Manchester, Robert Robinson, and a prototype of a safety coffin. He was laid to rest in a mausoleum fitted with a special door that could be opened from the outside by the watchman on duty. Inside Robinson’s coffin was a removable glass panel. Before his death, Robinson had instructed his family to periodically check on the glass inserted in the coffin. If the pane of glass had indications of condensation from his breath, he was to be removed immediately. However, the first true recorded safety coffin was for Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick before his death in 1792. The coffin included an air tube, a lock to the coffin lid that corresponded with keys he kept in his pocket, and a window to allow light in.

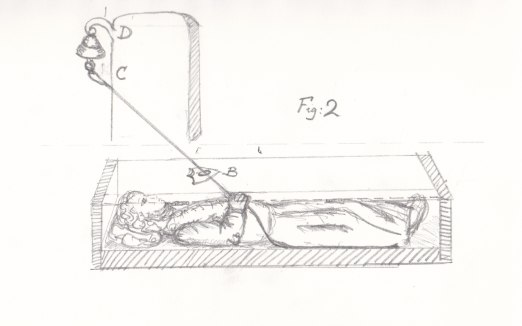

1892 saw the rise of the bell system, created by Dr. Johann Gottfried Taberger. Bells housed above ground connected to strings attached to the body’s head, hands, and feet. If the bell rang, the cemetery watchman would insert a tube into the coffin and pump air using bellows until the person could be safely evacuated from their grave. However, due to the process of natural decay, a swelling corpse could activate the bell system leading to false beliefs those buried inside were alive. Despite its popular use, there is no record of a safety coffin saving anyone.

Many of the old burial customs from history resurfaced as fables and idioms we use currently. Some experts believe the idiom ‘saved by the bell‘ originated from the use of safety coffins.