After the passage of the 18th Amendment made Prohibition the Law of the Land, legislation was required to establish the definitions of what exactly was being prohibited. The Dry faction in Congress, flush with their moral victory over demon rum, turned to a member of the Anti-Saloon League to draft the bill necessary to identify what was illegal and define the means of enforcing the new law. Wayne Wheeler was an attorney and a rabid supporter of the total prohibition of alcohol and wrote the new law under the sponsorship of the powerful Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Andrew Volstead. The Volstead Act, (which was vetoed by President Woodrow Wilson but the veto was overturned by Congress) became the impetus for the era of American History known as Prohibition.

It was soon clearly evident that the political shenanigans and blatant falsehoods which had led to the passage of the 18th Amendment did not reflect the opinions of the majority of American citizens. Politicians, judges, law enforcement personnel, veterans returning from the trenches of Europe, executives, laborers, farmers, clergy; a large representative majority of people from all walks of life opposed and blatantly ignored the new law. A new lexicon entered the American language; words like bootlegger, bathtub gin, blind pig, white lightning, hooch, giggle water, and many more colorful terms were soon overheard in everyday conversation.

While many preferred to take their illegal (and presumptively immoral) alcohol at home, others still preferred dressing up and going out to enjoy the conviviality of friends and music. Their destination, in cities all across the country, was defined by another new American word – the Speakeasy.

Here are some famous – and infamous – speakeasies from the Prohibition Era.

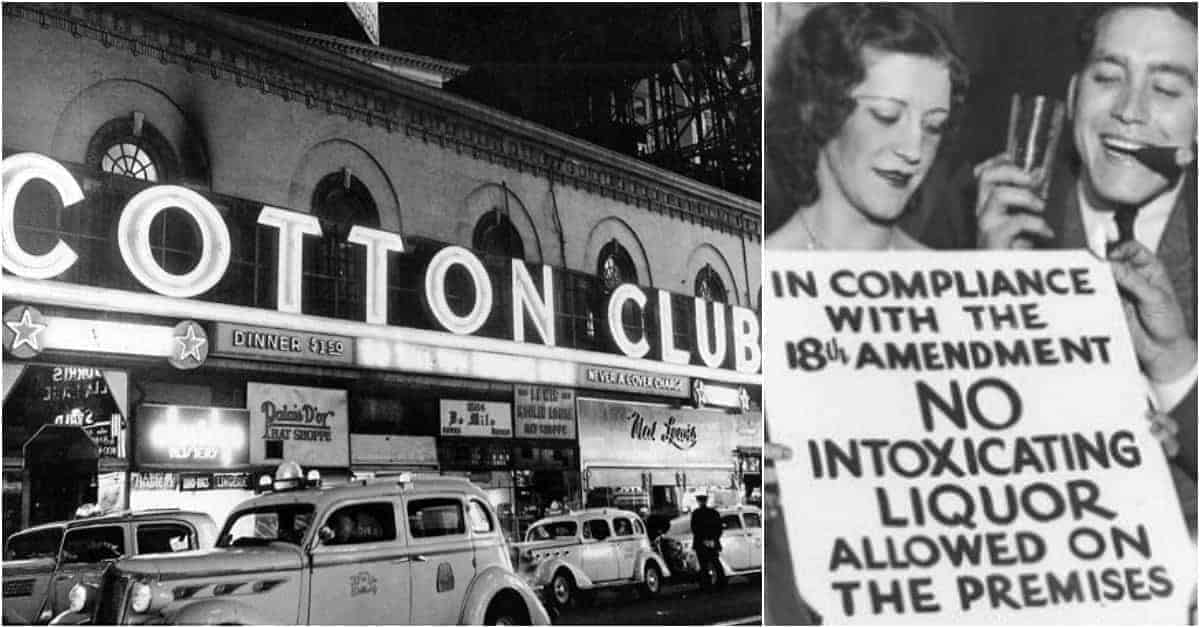

The Cotton Club

The Cotton Club opened in Harlem on Lenox Avenue at 142nd Street in 1923, as the enforcement of the Volstead Act was being reluctantly assumed by local authorities, many of whom were soon avid customers. Despite its location in a predominantly black neighborhood, the club was exclusively for white clientele, although it provided entertainment from the leading Black performers of its day.

Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Billie Holliday, a young Lena Horne, and many others headlined shows during the Cotton Club’s glory days. Their audiences included luminaries such as George Gershwin, Al Jolson, Broadway composer Richard Rogers, Jimmy Durante, and frequently the Mayor of New York, Jimmy Walker.

The Cotton Club in the twenties was operated by Owney Madden, a bootlegger whom’s profession was not a secret. Perhaps because the Mayor was a regular customer the club had little trouble with the authorities. Shut down briefly in 1925, it soon reopened and Madden found his primary business – brewing beer and importing liquor – to be well supported by the club’s taps and bars.

Madden used his profits from the sale of smuggled Canadian Whisky to corner the market on local taxis and milk delivery routes. The milk, in particular, ar were useful in helping to establish a delivery service for his contraband directly to the door of his best customers. Madden hired a personal driver to convey him through the streets. This driver – George Raft – would later establish a Hollywood career portraying gangsters and bootleggers. Madden quickly expanded his club activities across New York, eventually owning all or part of twenty speakeasies and clubs.

The Cotton Club welcomed the end of Prohibition and continued operating as a legitimate club at the original location until 1936 when race riots led to its closing. It reopened in the Theater District later that year, but never achieved the notoriety of the glamour years of Prohibition when it was well known as one of New York’s most popular speakeasies.