Ah, vampires. You can’t move without bumping into a handsome, fanged aristocrat these days. But despite their self-professed ancient lineage, the vampire as we know it isn’t all that old. That said, fears of the dead rising and harming the living have a truly ancient pedigree. Vampires, or vampire-like beasts, were once the last thing you’d dream of falling in love with. We’ll trace these old tales and beliefs across the world, then see how the modern vampire evolved. Best keep the lights on, and grab a crucifix…

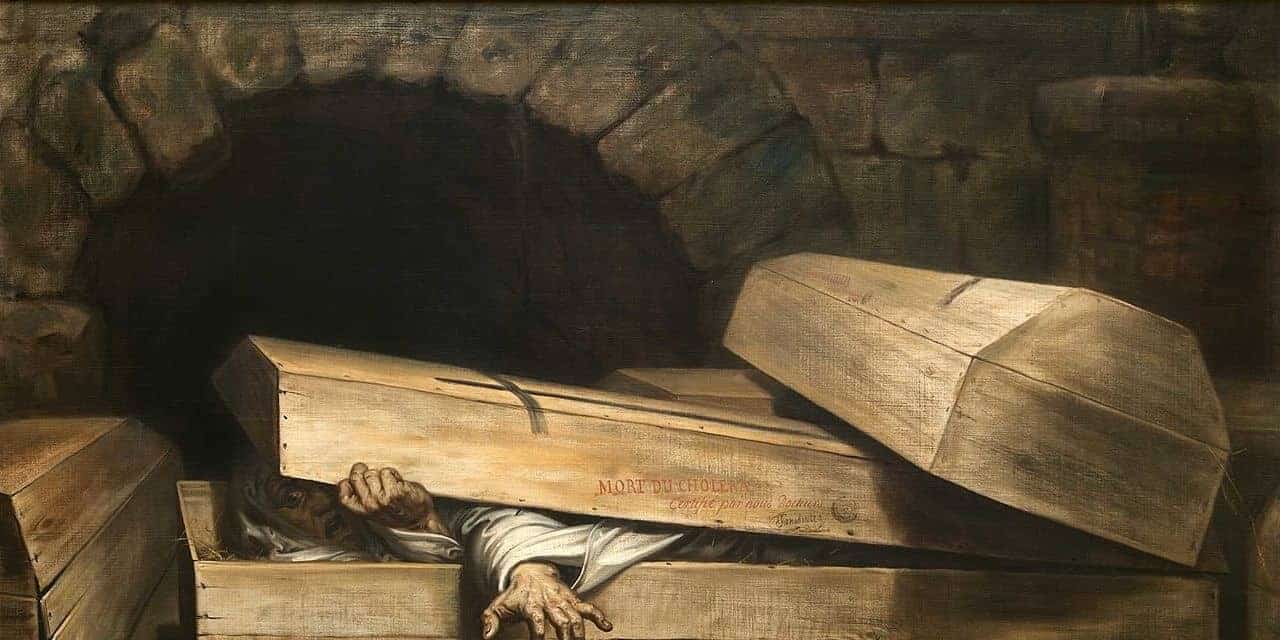

40. The idea of the walking dead probably came from people not understanding how bodies decompose

Contrary to popular opinion, bodies don’t rot overnight. After you die, your body goes into rigor mortis, but then weirder things start to happen. As the skin shrinks back, teeth and nails can appear longer. Gases build up as the internal organs decompose, bloating the body. Simultaneously, bloody foam leaks from the mouth. After this, the body takes on a reddish hue. Taken together, we have a bloated, bloody-mouthed, rosy-cheeked dead body with long nails and teeth: remind you of anything? Some historians think people’s unfamiliarity with the stages of decomposition led to myths of the cannibalistic walking dead.