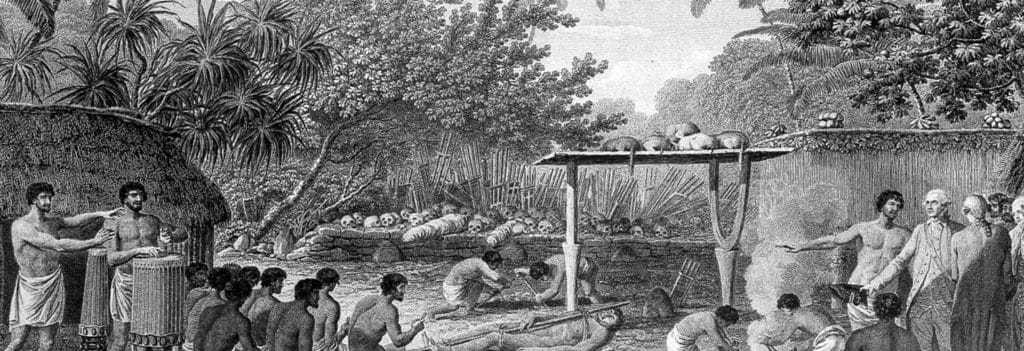

No nation has tried to take over native nations quite like Great Britain, who spread their English colonies all over the globe. While many native civilizations put up a good fight, the native Maori people of New Zealand just may have been the most difficult culture for the English to take over. Before setting foot on the shores of New Zealand, explorers had no idea that they were about to come face-to-face with tribes of warrior cannibals.

Both men and women had tattoos all over their bodies that had been carved into the skin, and they carried severed human heads on sticks as trophies from their conquests. Without a way to properly communicate with one another, simply appearing on the shores of New Zealand was interpreted as a threat. Despite the fact that they had superior weapons, the Europeans were so terrified of the Maori, it took over 200 years for them to begin settling proper colonies in New Zealand. Even then, there were several incidents of mass murders, battles, and trade wars.

The First Encounter at Golden Bay

In 1642, Abel Tasman was the commander of the powerful Dutch East India Company. He heard rumor of a huge uncharted island country near Australia called “South Land” that was never inhabited by Europeans. He sailed two large ships named The Heemskerck and The Zeehaen to the location of this mysterious island. When they found New Zealand, they anchored their ships near a cave. Unbeknownst to them, the cave was part of a Maori legend where a giant lizard monster called “Ngara Huarau” was said to be contained. Every Maori knew to keep away from the cave. They believed that if any humans got too close, the monster would come out and eat everyone.

The morning after the Dutch crew anchored their ships to shore, a group of Maori natives rowed a small boat towards the Heemskerck and Zeehaen, and blew a horn. Since the Maori had never seen white men before, and they were anchored so close to the dreaded monster’s cave, some researchers believe that they must have thought that Europeans were evil spirits, and the horn was meant to scare them off. Abel Tasman was completely naive to their culture, of course, and he thought that playing the horn was some kind of friendly musical exchange, so he asked some of his crew to play musical instruments. Little did he know that responding to a horn call with more horns was like saying, “Bring it on.”

Based on the Maori men’s reaction, he realized what he had made a big mistake. Confused and scared, Tasman ordered his crew to set off their canons into the air. This scared the Maori men in the boat, and they rowed back to shore. Word quickly spread about the foreign invaders among the rivaling Maori tribes, and they all decided to ban together to fight this new common enemy.

The next day, a group of Maori people was standing on the shore with knives and waving. This should have been an obvious sign of hostility, but a handful of men rowed out on their small boats again towards the Dutch ships. When they started waving, they interpreted this as a friendly gesture. The crew of The Zeehaen began to encourage the Maori to come on the ship. Meanwhile, the crew of The Heemskerck could see the guys with knives on the shore, so they rowed a boat over to their friend to let them know it wasn’t such a good idea to allow them onto the ship. When they began to row back, the small Maori boat rammed into them, and they began clubbing the Europeans, aiming for their heads and necks.

The survivors had to jump off of the boat and swim towards the bigger ship, and the sailors started to shoot their guns at the Maori men who were killing their comrades. After recovering the bodies of the dead Dutchmen, they decided to call it quits. Not only were the Maori crazy dangerous, but they were also running out of food and water.